![]()

Chapter 2: Industry

Section 1: Construction of large scale government operated factories

During the advancement of the major powers of the United States and Europe into Asia in the latter half of the 19th century, Japan sought to establish capitalism as a pathway to independence. Under the policy of Increase Production and Promote Industry pursued by the Meiji government, the former Shogunate government and domain owned western style factories and mines were confiscated in order to realize a government-led top-down capitalism. The Ministry of Engineering, which was established in 1870, was in charge of centralizing the first government enterprises, inviting a large number of engineers and experts as hired foreigners and provided guidance. The Yokosuka Shipyards in particular, which were founded in the last days of the Tokugawa shogunate with support from France, contributed to development of other industries by means of machinery production and cultivation of engineers as the largest comprehensive factory within Japan at the time. It was possible to acquire skills through Japanese workers and female factory workers in these government controlled factories, and the transfer of the skills to the wider populace, along with the disposal of the government control itself, served as the basis for the development of industrial capitalism in Japan.

Yokosuka Shipyards

After the Opening of Japan, the Shogunate government, which had established a navy, embarked on the construction of a Japanese-made warship. Through commissioner of finance OGURI Tadamasa (1827-1868) and inspector KURIMOTO Joun (1822-1897), Roches contacted the Shogunate government, and concluded an agreement for the construction of ironworks in 1865. Yokosuka, which had similar geographical features to France's Toulon naval port, was selected as the construction site, and French navy engineer François Léonce Verny (1837-1908), who was stationed in Shanghai, was invited to head the project. After the Meiji Restoration, the construction of the shipyards was continued by the new government, and functioned as a comprehensive factory for supporting the policy to Increase Production and Promote Industry, including iron-making and shipbuilding. The shipyard continued to exist as the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal until defeat in the Second World war, and after the war it served as a Naval Shipyard of the US military in Japan, a role in which it continues today. (The name Yokosuka Shipyards was changed to steelworks, shipyard, naval shipyard, naval arsenal, etc., however, excluding cases where it is necessary to specify the name used for a particular period, this exhibit uses the name "Shipyards" as the general name.)

Yokosuka kaigun senshō (Ed.), Yokosuka kaigun senshōshi, Yokosuka kaigun senshō, 1915 [224-207]

This is an official history of the Yokosuka Shipyards from 1864 to 1898, published by the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal in 1915, on the 50th anniversary of the foundation of the Yokosuka Shipyards. Accounts from before 1870 are from SUZUKI Shigeto's Yokosuka Senshōshi (1887). Materials covering the period after those covered in this text include the Yokosuka Naval Arsenal edition Yokosuka Kaigun Kōshōshi (1935).

During the construction of the Yokosuka Ironworks, first factories were established in Yokohama, machine tools already in Japan were collected, and Japanese workers were trained in the skills, andthe machinery required for the construction of the ironworks were manufactured. The official translators who worked on the negotiations with the French included SHIODA Saburo (1843-1889), who worked on revision of the unequal treaties as a diplomat, NAMURA Taizo (1840-1907), who was involved with the invitation of Gustave Émile Boissonade (1825-1910) and served as head of the supreme court, IMAMURA Yūrin (1845-1924), who formed the basis of French education, and other individuals who played an active role in various fields.

Yokosuka zōsenjo (Ed.), Heimen kikagaku, Yokosuka zōsenjo, 1878 [24-137]

The proposal for establishing the ironworks presented by Verny to the Shogunate government stated, "It is necessary for the government (Shogunate) to establish a school inside the shipyard to foster engineers so that in the future Japanese workers could construct ships instead of the French workers" (Yokosuka Kaigun Senshōshi), showing that there was a plan for a system for transfer of skill from the beginning. The system for transfer of skills was temporarily halted after the Meiji Restoration, however in 1870, a skills school called "Kosha" was established, and taught naval architecture and mechanics in French. The acquisition of French language skills was considered important, and individuals who used the language skills they had acquired to make a living, such as KAWASHIMA Chūnosuke (1853-1938), who worked on translation of French literature, began to appear in greater numbers. It seems that from around 1876, when Verny and other hired foreigner French were dismissed, education was altered to be taught in Japanese.

This text is a textbook on plane geometry. Mathematics was a compulsory subject in the education at Kosha.

Tomioka Silk Mill

After the Opening of Japan, the major export of Japan was raw silk. At the time in Europe, there was widespread disease spreading among silkworms, and the production quantities of major silk producing countries, including France, decreased drastically, and raw silk was exported in great quantities from the open port of Yokohama. However, the great demand led to poor quality, and malicious manufacturers ran rampant. In order to work towards improving the quality of the raw silk, which was a major export product, in 1872, the Meiji government constructed a government operated silk mill in Tomioka, Gunma Prefecture. In the operation of the Tomioka Silk Mill, technologies were imported from France, which possessed the largest silk producing region in Europe, Lyon, and French experts were hired under the leadership of Paul Brunat (1840-1908). Tomioka Silk Mill produced significant results in terms of training of female workers and other technique and technology introductions, however the management during the government operated period was not adequate, and in 1893 it was transferred to the Mitsui Finance Group. The managing organization changed again thereafter, but the mill continued operation until 1987 under Katakura Industries Co., Ltd.

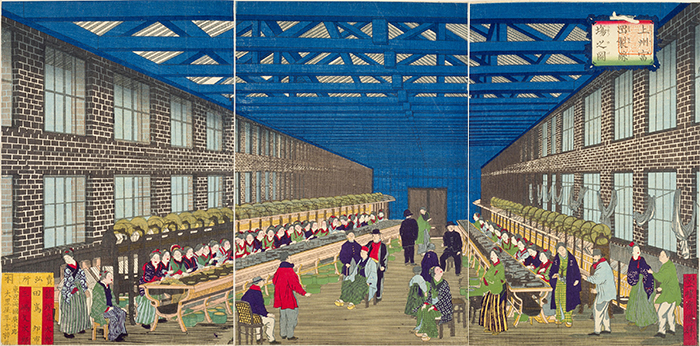

Ichiyōsai Kuniteru, Jōshū Tomioka seishijō no zu, Daikokuya Heikichi, [1872] [寄別7-4-2-5] ![]()

TAMANO Seiri and SUGIURA Yuzuru, Sōshijō toritate nisshi, 1870 [Papers of SUGIURA Yuzuru, #146]

In June of 1870, Brunat, who was stationed in Yokohama as a raw silk inspector in the employ of Hecht Lilienthal & Co., was hired by the government to select the location for the silk mill. The government supervisors were OKI Takato (1832-1899), TAMANO Seiri (1825-1886), SUGIURA Yuzuru (1835-1877) of the Ministry of Civil Affairs, and SHIBUSAWA Eiichi of the Ministry of Finance.

This text is a journal of events from October 17, 1870 to the October 7 Intercalary of the same year, maintained by TAMANO and SUGIURA who negotiated with French legation secretary Albert Charles Du Bousquet (1837-1882) and Brunat on the construction of the silk mill and the hiring of French workers. The name of ODAKA Atsutada (1830-1901), the brother in law (first cousin) of SHIBUSAWA and the first head of the Tomioka Silk Mill, also appears in the text.

SUGIURA Yuzuru, Kyakuchū zakki, 1870 [Papers of SUGIURA Yuzuru, #145]

These are memos by SUGIURA from the October 13 Intercalary to November 5, 1870. The content mainly consists of surveying the site in Tomioka together with Brunat. It shows that before the construction of the silk mill, Brunat and others carried out detailed surveys of the site including the geographical features, wind direction and water supply. SUGIURA served as a diplomat, travelling to France twice during the last days of the Tokugawa shogunate, and worked to establish the postal system at the Ministry of Civil Affairs after the Meiji Restoration.

The facilities for Tomioka Silk Mill were designed by Edmond August Bastien (1839-1888), a French draughtsman who worked at the Yokosuka Shipyards, and the group of kawara tile roofed, wooden structure, brick buildings, was registered to the UNESCO World Heritage List as a Cultural Site in June of 2014.

Seizō kikai hinmoku, Tokyo Akabane kosakubunkyoku, 1881 [特55-103]

The Akabane Engineering Agency took over western style iron working machinery donated by the Saga Domain to the Shogunate government, was established as Ironworks Bureau in Akabane, Mita, Tokyo in 1871, and was later made a subordinate agency of the Ministry of Engineering Machinery Bureau in 1877. Until it was transferred to the Ministry of the Navy in 1883, it supplied the needs of the government and private sector as the core of the machine industry division, and supported the Ministry of Engineering policy to Increase Production and Promote Industry. This text is thought to be a product catalog of the subordinate agency in 1881, and has both Japanese and English explanations. The "Horizontal Engine. High Pressure" (steam engine) (Frame Number 7) and "Silk Spinning Mill" (Frame Number 54) were improved versions of the imported machinery used at Tomioka Silk Mill. The French style silk spinning mill with included Cocoon Pan was used only at Tomioka within Japan at the time.

WADA Eiko, Shinano kyōikukai (Ed.), Tomioka kōki, Kokonshoin, 1931 [特210-926]

Tomioka Silk Mill was established as a model factory for the introduction of western techniques and technologies, and aimed at transferring skills to female workers who applied from all over the country. The author, WADA Ei (ko) (1857-1929) was born as the daughter of a Matsushiro Samurai in Shinano no kuni (Nagano Prefecture), joined the Tomioka Silk Mill in April of 1873 and worked as a first-class worker until July of the following year. After returning home, she worked instructing the female employees when the private operated Saijo Silk Mill (later to become Rokkosha) was established, and in 1878 she was appointed an instructor at the Nagano Prefectural Silk Mill. She left the silk industry in 1880 when she was married, however she left behind a series of texts recording her memories of the time from 1907 onward. These were edited in 1931 by the Shinanno Kyoiku Kai and published under the titles Tomioka Nikki and Tomioka Kōki, and are extremely valuable materials which provide an insight into the actual conditions of a female worker at the beginning of the Meiji Era. In the latter book, she provides recollections of the time around the establishment of Rokkosha, showing how the techniques and skills learned at Tomioka were spread to various regions of the country by the female workers who learned them.

Ikuno Mine

Ikuno Mine in Asago City, Hyogo Prefecture produced silver, copper, lead, zinc, tin and other products. There are a variety of stories regarding the discovery of the mineral deposits in the mine, however full-scale mining is said to have begun there during the Sengoku era. Together with Sado goldmine it was an important mine which supported the finances of the Shogunate government, however the quantity of output dropped drastically in the last days of the Tokugawa shogunate. The Meiji government worked to improve the operation of the mine as a government operated mine by introducing new technologies, and invited French mining engineer François Coignet (1835-1902), who had worked to stimulate the mining industry in the Satsuma Domain. The mine was equipped with steam engine-run elevators, carts roads for transportation and other features and output gradually increased. Thereafter, it became Imperial property, and then was transferred to the Mitsubishi Limited Partnership Company in 1896 and continued in its possession until the mine was closed in 1973.

Francisque Coignet, ISHIKAWA Junkichi (Ed.), Nihon kōbutsu shigen ni kansuru oboegaki, Hanedashoten, 1944 [561.11-C83ウ]

This is an essay by Coignet on Japan's geological structure, current mine conditions, traditional metallurgy, and mining methods. It was posted to the French National Mining Association newsletter. The essay records geological observations by Coignet himself from within the Satsuma Domain, Ikuno, Besshi, etc. as well as descriptions of other regions based on limited government statistics, showing the variation of detail of the differing reports.

After graduating the National School of mines (the Grandes Ecoles), Coignet worked as a mining engineer within France and it's colonies, was introduced by Count Charles the Cantons of Montblanc (1832-1893), who was active in Japan French relations during the last days of the Tokugawa shogunate, to member of the Satsuma Domain GODAI Tomoatsu (1835-1885), who was studying in Britain, and in 1867, came to Japan in order to carry out mine surveys in the Satsuma Domain. After the Meiji Restoration, he was involved in technical instruction at the Ikuno Mine, and worked on preparing the facilities, etc. He also played a large role in determining the presence of metal in the ore and returned to France in 1877.

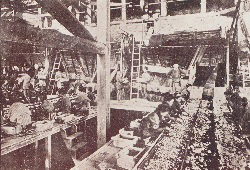

FUJIWARA Ichinosuke, Ikuno kōzan shashinchō, Kobayashi shashinkan, 1909 [特47-101]

ASAKURA Moriaki (1844-1924), who studied abroad with GODAI and others from the Satsuma Domain, was dispatched as the supervisor for the government controlled Ikuno Mine. During the former Shogunate government, the ownership rights for the mine belonged to the government, and the mining rights were granted to the hereditary prospectors, so when it was made government controlled, there was a great deal of resentment from the prospectors. In 1871 the mine was burned and the majority of the new equipment was lost in the fire. ASAKURA imposed severe punishment and pushed to restore the works. Until resigning as Commissioner of Imperial Property Bureau, Chief of Ikuno Branch in 1896, he worked as the supervisor for mines for a quarter of a century.

This book is a photo album conveying the state of Ikuno Mine from the early to mid Meiji Era after the restoration. The photos show that modern equipment was used in ore selection and refining.

TAKASHIMA Hokkai (Tokuzo), Shasan yōketsu, Toyōdō, 1903 [187-251]

As with the Yokosuka Shipyards and Tomioka Silk Mill, the transfer of western style technology and skills was aimed for at Ikuno Mine, and it is known that a mining school was opened in 1869. TAKASHIMA Tokuzo (pen name Hokkai, 1850-1931), who later came to be known as a Japanese-style painter, was assigned to Ikuno in 1872 as an employee of the Ministry of Engineering Mining Bureau, and learned French and geology from Coignet. In 1874, he wrote San'yo San'in Chishitsu Kiji based on observations made on a return to his home town of Yamaguchi. From 1878 he worked in the Ministry of Home Affairs Geography Bureau, and created the first Japanese-produced geologic maps, the Yamaguchi Ken Chishitsu Bunshokuzu and the Yamaguchi Ken Chishitsu Zusetsu. Thereafter, he transferred to the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce, and was instructed to study abroad at France's National School of Forestry of Nancy (the Grandes Ecoles) for 3 years from 1885. In France, his sketches were highly acclaimed, and he became active as a painter after retiring from his position in the Ministry of Agriculture and Commerce. This book includes mountain sketches and a geological map of the Japanese islands on the last page, and there is an explanation of his painting methods for pictures of mountains based on his geology and forestry knowledge.

Hired foreigners at the Ministry of Engineering

In 1870, at the suggestion of British engineer Edmund Morel (1841-71), who was invited to work on the construction of railroads, the Ministry of Engineering was established as a government office for overseeing industrial fields. This was carried out in order to follow along the route laid out by OKUMA Shigenobu (1838-1922) and ITO Hirobumi (1841-1909), who promoted an enlightened policy based in the Ministry of Finance merging the Ministry of Civil Affairs. The Ministry of Engineering carried out operation of government enterprises in 3 fields of railroads, mining and machine tools thereafter until it was abolished in 1885. In contrast to the Ministry of Home Affairs, which strove to foster indigenous industries, under the policy of Increase Production and Promote Industry, the Ministry of Engineering promoted rapid introduction of western techniques and technologies. This made the management of government enterprises fragile, and is thought to have led to the transfer and disposition of these enterprises.

Kōbushō enkaku hōkoku, Ōkurashō, 1889 [26-333]

This book is a historical record of the Ministry of Engineering compiled by the Ministry of Finance in 1888 after the Ministry of Engineering was abolished. The content includes records for each of the enterprises under each bureau of the ministry and the Engineering Academy in the mining, railroad, communications, lighthouse, machinery and building and repair fields. Lists of the names of the hired foreigners for each bureau are included, showing that British were by far the most common nationality employed, however in mining, shipbuilding and other fields, many French names are also found, giving an indication of France's influence.