HOME > What Are Historical Materials?

History is an account of events that took place in the past, as related to contemporary persons in a coherent, easily understandable narrative. The fact that history is often taken to be a "story" is a result of its aspect as an "easily understandable narrative." Yet in the past, history used to overlap with literature and religion, and even today, the line between history and literature is not necessarily so distinct.

The materials that are used to build up that narrative of past events are called "historical materials". Historical documents written on paper soon come to mind, but there are actually many other forms of historical materials, including oral transmissions, stone inscriptions, paintings, recorded sounds, images (photographs, motion pictures), and so forth. Even ancient relics and ruins, broadly speaking, are historical materials.

In historical research, each historical material differs as to the extent of its validity and reliability (authenticity), and the task of ascertaining that difference is called "historical judgment". Taking historical documents as an example, the yardsticks commonly used to judge the criteria of validity and authenticity are the three elements of "when", "where", and "who", that is, when were they written, where were they written, and who wrote the documents. Historical documents in which all three conditions (i.e., they were written by persons at specific times and places) are designated "primary historical materials", and those which do not are considered "secondary historical materials".

Representative examples of primary historical materials are diaries, letters, and public documents. The Constitutional Government Documents Collection at the National Diet Library contains a large number of diaries and letters written by politicians and statesmen (including military and bureaucrats) from the end of the Tokugawa Shogunate to the postwar Showa Period (1945-1989). While the national public documents in Japan are kept, as a rule, in the National Archives of Japan, there are also many public documents and manuscripts among the holdings in the Constitutional Government Documents Collection. Diplomatic documents are maintained in the Diplomatic Record Office of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and documents from the prewar Army and Navy Ministries are kept in the Military Archival Library of the National Institute for Defense Studies. The historical materials displayed in the current exhibition all give us the vivid sense of being present at the scene since they were written at the time and place in which protagonists moved.

Diaries, were written in times long past, as memoranda by nobles-describing part in specific ceremonies, but in modern times, diaries are basically a record of activities and events written by an individual. Accordingly, reading through a person's diary allows us to follow and relive his actions over a long span, and is also beneficial in that it lets us easily understand the author's interpersonal relations. While this may be an exaggerated description, diaries allow us to perceive the time and environs that surrounded that person. Moreover, a diary quite frequently describes the author's inner world and private affairs. These are strength that diaries have over other kinds of historical materials, and is why researchers always look for diaries first when doing research based on historical materials.

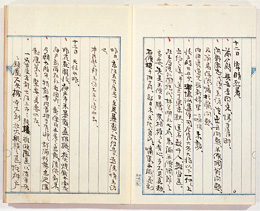

KURATOMI Yuzaburo' diary 1926 (Taisho 15)

Diaries, naturally, are not the end all of historical documents. Given the limited capacity of human beings to collect information and perceive things, it is not surprising what people write often contains mistakes and is incomplete. Another problem is that diary entries often end up not getting written at all during wars and political turmoil on account of the protagonist's extraordinary workload or exhaustion. Occasionally, we see a note appended to a diary entry saying, "especially written for posterity's sake", making us want to seize upon it, but we must be careful not to be too hasty. This is because this is evidence of the protagonist's self perception as a major character upon the stage of history.

DEN Kenjiro's diary 1918 (Taisho 7)

While diaries are historical documents allowing us to grasp a given period of time and environ, letters are snapshots of an extremely limited time span. One may, therefore, conclude that letters suffer in comparison to diaries as historical materials, but this is hardly the case. That is because diaries are introspective, written to oneself, while letters are outwardly directed, written to others. Thus, they reveal in an extremely straightforward fashion, the various types of bargaining, information exchange, etc. existing within the political and social relationships that the author had with others. Letters frankly express every aspect of human relationships between two people, such as superior/inferior, intimate/estranged, shared/different interests, gain/loss calculations, real intentions/expressed reasons, admissible/non-admissible statements, secret revelations/deceptive leading on.

Whereas diaries represent the expression of one's mental processes with relatively few restrictions, letters directed to another person are subject to many restrictions based on the relationship in question. As letters represent the author's face to the external world, one can say that they present rather clear boundaries of the writer's political and social relationship.

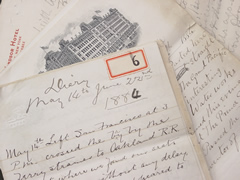

SAITO Makoto's english diary 1884 (Meiji 17)

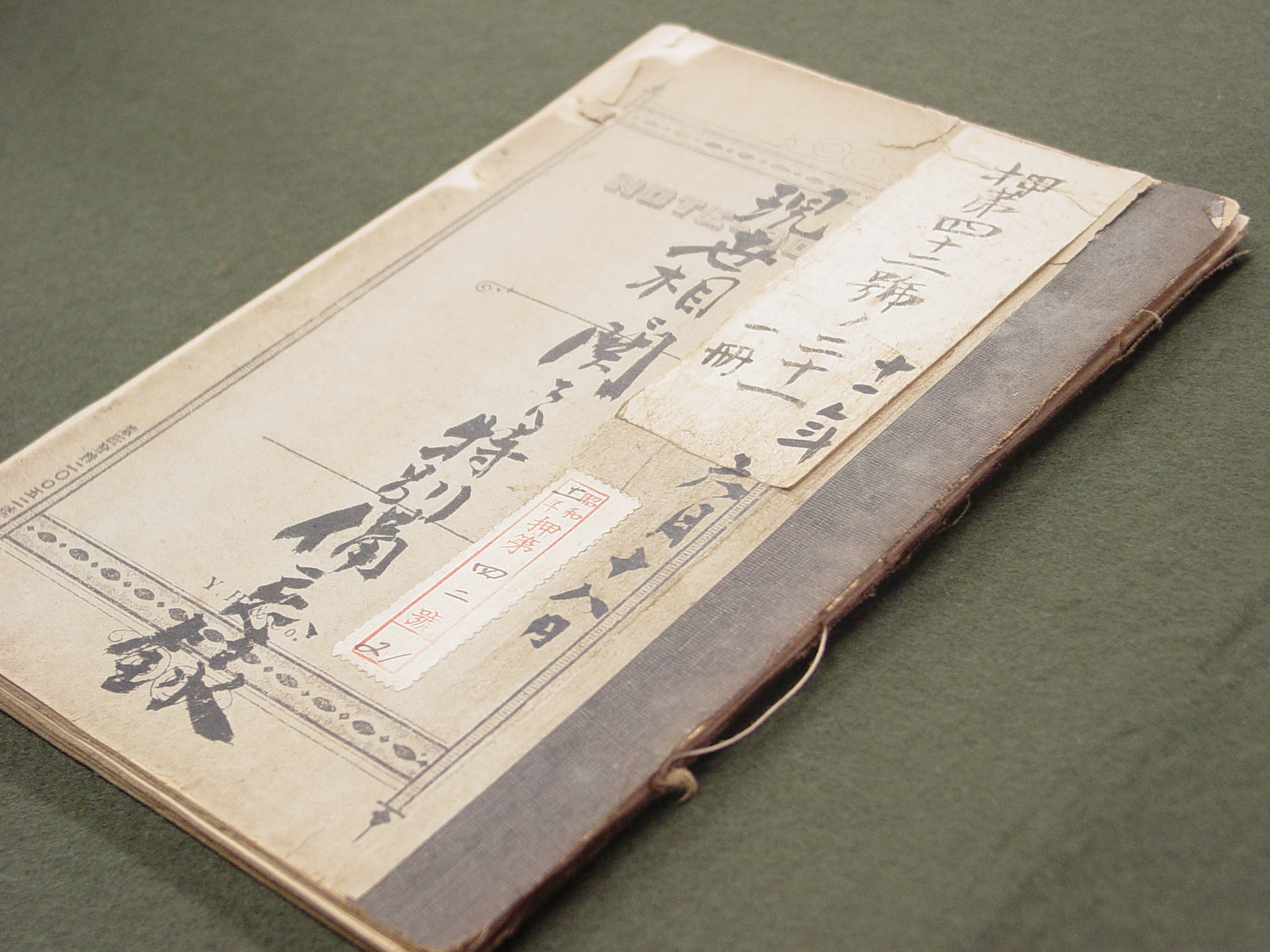

MASAKI Jinzaburo's diary June,1936 (Showa 11) label of confiscation

Diaries and letters, which are personal activities, reflect the individuality of the writer, and thus each displays characteristics unique to the principal. KURATOMI Yuzaburo's diary was unparalleled in its length, with just one year's worth of entries filling up A5-sized 18 notebooks; FUJINUMA Shohei wrote his diary by skipping lines; SAITO Makoto wrote his in English; DEN Kenjiro wrote his diary using the Japanese style of classical Chinese writing; ITO Miyoji's diary slips back and forth between such mundane things as bonsai cultivation (he even has gastronomical entries) and more weighty things such as the affairs of state. The diary of MASAKI Jinzaburo, who was implicated in the 2.26 Incident of 1936, was seized by the Military Gendarmery, a fact made graphic by the seals stamped on it.

Meanwhile, the style of calligraphy used in correspondence in Japan changed greatly around the year 1877 (Meiji 10). This resulted from a new calligraphy style imported from Qing-dynasty China, coupled with the Oie style of calligraphy (used in official Tokugawa documents) losing popularity; some nobles already had started adopting the new calligraphy style even before it was widely accepted. Just as one might expect, court nobles were indeed intellectuals. The upward slanting parallelogram style of printing characters is a quirk of the high strung and prideful, and that precisely describes the handwriting style (of people such as the soldier/statesman) of YAMAGATA Aritomo and TOKUTOMI Soho; moreover, the two had a close relationship. The handwriting of such people as MATSUKATA Masayoshi, OURA Kanetake, OKI Takato, GOTO Shojiro are difficult to read enough to make scholars weep, such is the hidden pleasure and challenge of reading historical materials in the original.

Incidentally, Meiji era letters were mostly official so the envelopes lacked stamps. With an emphasis on reliability and confidentiality, the preferred way to send letters was via messengers; still, the regular post was also used from time to time. Among the stamps used, one often comes across new and old koban stamps, but unfortunately none of them have any collector's value.