Sugoroku Board Games from the Edo Period

- Kaleidoscope of Books

- Famous Places, People, and Social Customs on Paper

- 3rd Move: Social Customs

- Start

- 1st Move: Visiting Famous Places

- 2nd Move: People

- 3rd Move: Social Customs

- Conclusion/References

- Japanese

3rd Move: Social Customs

After the Sengoku period came to an end, the Edo period because an age or social stability, during which townspeople gained economic power and played a significant role in promoting culture. Not surprisingly, the diverse culture of the townspeople was also depicted in sugoroku. In this chapter, we will take a look at sugoroku that feature the aspirations of townspeople to succeed in life, local specialties and other products, popular shops in Edo, and unusual hobbies.

Social Mobility

During the Edo period, a number of sugoroku depicting people’s dreams of advancing their social status were created. Most of these targeted ordinary townspeople, who were the primary customers of sugoroku. Because of the strict social class system in place during the Edo period, advancement within one’s own class was depicted, but not advancement beyond that. In many cases, the finish line features the attainment of great wealthy, which is an indication that financial security was considered a measure of success by townspeople.

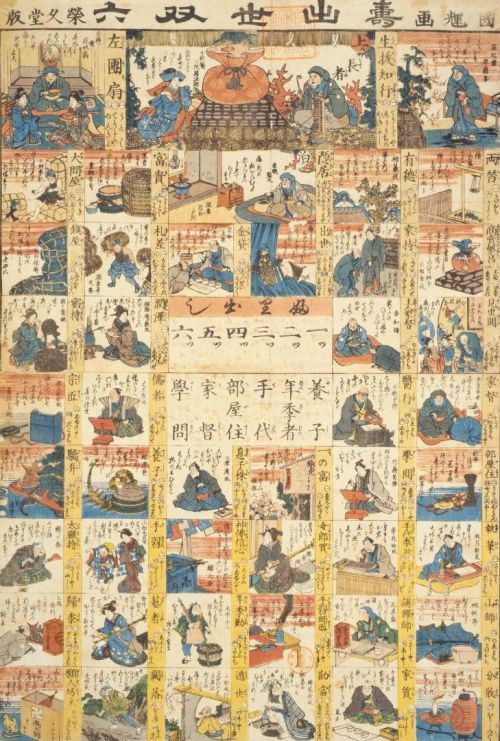

Kotobuki shusse sugoroku (Celebration for advancement)

This sugoroku features success stories of ordinary townspeople. It depicts several routes to success according to specific occupations. For example, the servant of a merchant, who advances to become a large wholesaler and finally a wealthy person himself at the finish line. A successful student advances to become a medical doctor or a Confucian scholar. The lowest row shows squares that are indicative of failure, such as disinheritance or ostracization, which gives us an idea of how ordinary townspeople viewed failure, as well.

There is square labelled retirement, which seems to be another finish line and says “If you reach this square, you will be granted a pension from a wealthy person.” There is also a square labelled ganninbozu, which is a street performer dressed as a Buddhist monk, who is paid to visit shrines and temples to pray on behalf of his clients. There are no further instructions here, probably because this was considered a dead end in one’s social advancement.

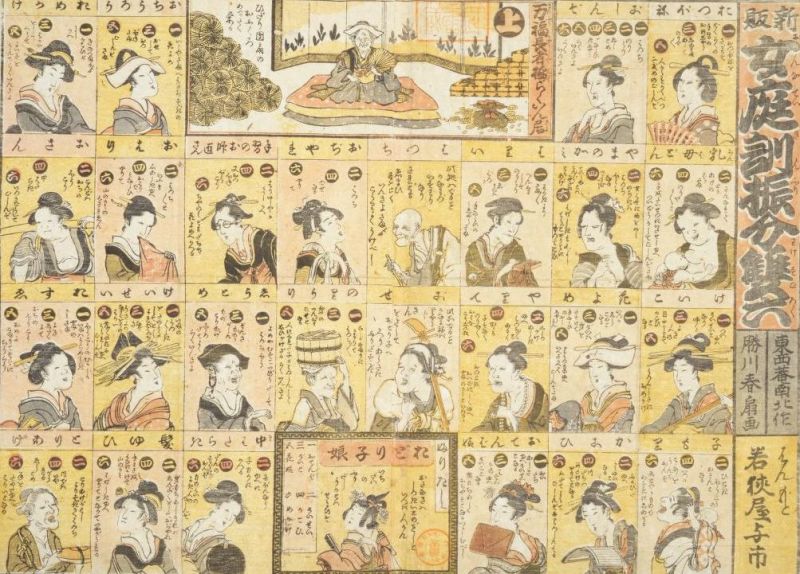

Shinpan onna teikin huriwake sugoroku (the latest in women’s upbringing)

This board is about the social advancement of women. The starting line shows a young dancer, and the finish line is a millionaire living in retirement in paradise. Each square depicts occupations and social status open to women at that time.

The instructions in each square describe future aspirations to the next step. For example, brides are instructed 1. to become a mother-in-law someday; 3. to become a teacher, since artistic skill leads to income; 5. to become the wife of a wealthy man by using your wits. (Each number indicates a roll of a dice.) Thus, the game provides stories for a successful life.

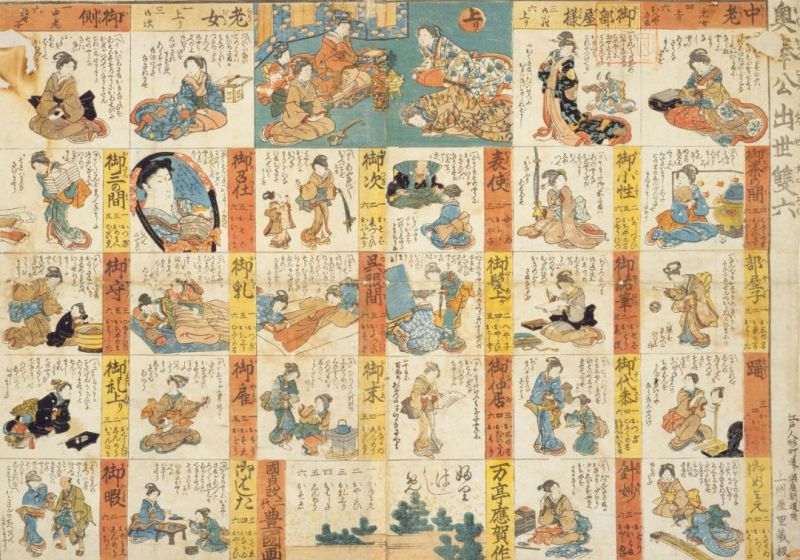

Oku hoko shusse sugoroku (Advancement at the inner palace)

This sugoroku depicts a woman's journey to the Ooku—the inner palace of the Edo Castle, where the Shogun's household lives. Various positions and roles are illustrated here: a servant who takes care of miscellaneous affairs, an older woman who is head of the ladies-in-waiting, and a concubine.

In reality, however, members of the Shogun’s household were rarely chosen from the townspeople, so this sugoroku apparently is depicting what is a fantasy of townswomen at that time. There is also a sequel by the same illustrator, featuring the upbringing of a young girl, entitled Oku hoko nihen musume ichidai seijin sugoroku (A girl’s growth and development)*.

*Published by Joshuya Juzo. [本別9-27]

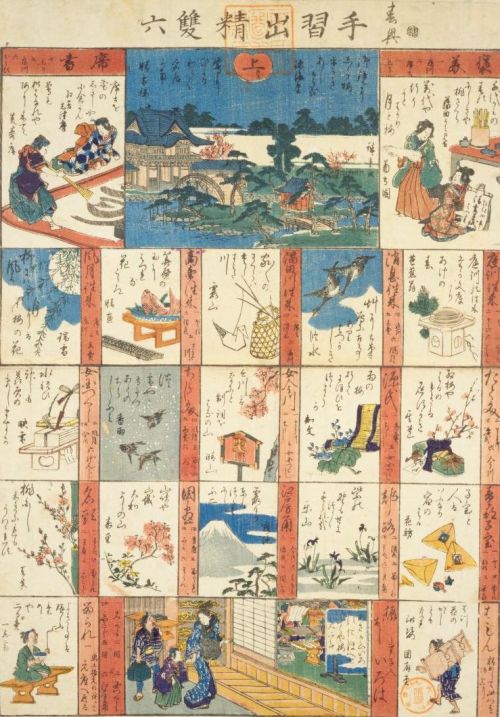

Shunkyo tenarai shusei sugoroku (Practice of Japanese calligraphy)

This sugoroku features children practicing Japanese calligraphy. The starting line depicts a little boy, taken by his mother to enter a terakoya, an educational institution that taught writing and reading to children during the Edo period. The finish line is Kameido Tenjin Shrine, where the god of learning is enshrined, and which is located in the present-day Kameido neighborhood of Koto City in Tokyo.

Various aspects of life at a terakoya are illustrated, including excommunication, detention, and rewards. We can also see the names of books with calligraphic examples, such as Genji, Onna imagawa, and Shobai orai.

Oraimono, collections of sample letters and sentences, were used as textbooks at terakoya. The students studied different curriculums, depending on their social status, intended occupation, and gender, so a variety of examples were published: rural correspondence and agricultural correspondence for farmers; commercial correspondence and wholesale correspondence for merchants; and carpenters’ correspondence for artisans.

Commerce

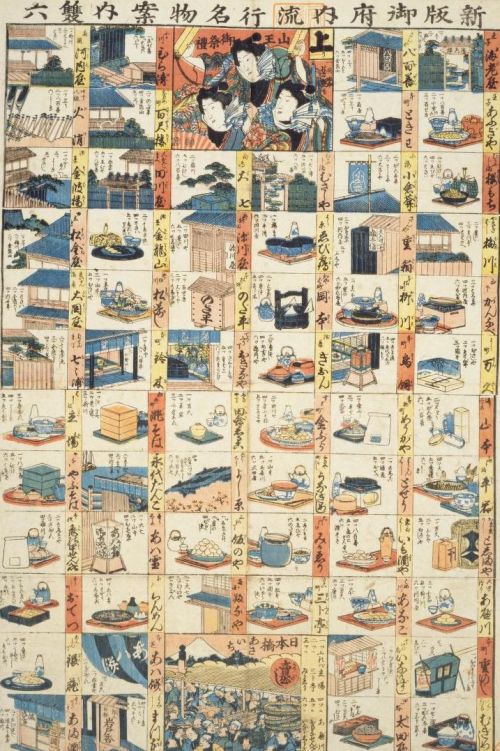

Shinpan gofunai ryuko meibutsu annai sugoroku (introducing the specialties of Edo)

The Japanese word for starting line is ordinarily furidashi, but here it is labeled uridashi, which is a pun meaning “bargain sale.” This sugoroku features popular restaurants that serve eel, buckwheat noodles, and others specialties, starting with the Nihonbashi morning market and ending at the Sanno Festival. This sugoroku is from the late Edo period, when culinary culture reached full maturity, resulting in a rapid increase in the number of restaurants as well as the publication of numerous cookbooks. Famous restaurants of the day like Yaozen in Sanya and Hirasei in Fukagawa appear in the squares.

Other Subjects

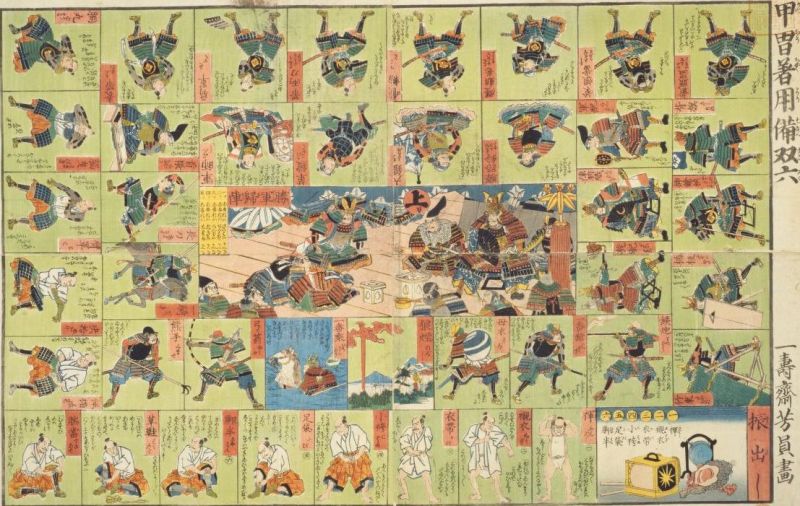

Kacchu chakuyo sonae sugoroku (Medieval armor)

This sugoroku shows the rituals a samurai went through when putting on armor, going into the battle, and celebrating a victory. First, he puts on fundoshi (Japanese loincloth), kobakama (pleated trousers), straw sandals, and chest armor. Then he picks up a matchlock rifle, steel rake, long sword, and other weapons, after which he puts on oyoroi (heavy armor) and jinbaori (surcoat). The finish line features a picture of the samurai returning to camp to celebrate a victory.

Utagawa Yoshikazu, a pupil of UTAGAWA Kuniyoshi, used several pseudonyms like Issen, Ittosai and Ichijusai. After the Port of Yokohama opened to foreign vessels in 1859, he drew many pictures that show the customs of Westerners, and some of these are held by the National Diet Library*.

*Gaikokujin ifuku shitate no zu (Westerner tailoring clothes), Maruya Jinpachi, 1860. [亥二-92]

Yokohama kenbutsu zue Ijin osanaasobi (children of Westerners playing on a hill), Joshuya Kinzo, 1860. [亥二-92]

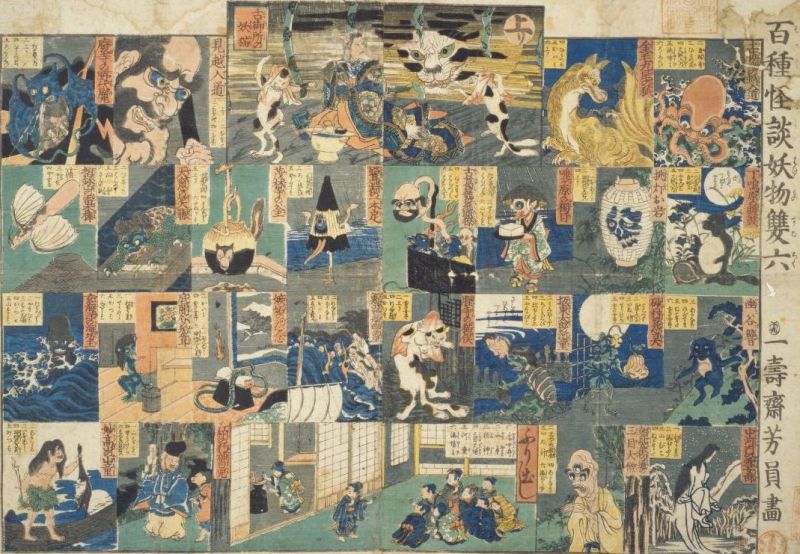

Mukashi banashi bakemono sugoroku (Old monsters and tales of horror sugoroku)

This sugoroku features colorful pictures of yokai—monsters from Japanese folk tales. The starting line depicts children enjoying a game of Hyakumonogatari*—the telling of ghost stories—and the finish line shows monstrous cats in a haunted house. Utagawa Yoshikazu, who created the Kacchu chakuyo sonae sugoroku shown above, also created this sugoroku. Ghost stories were popular during the Edo period and many anthologies were published, including Otogi boko by ASAI Ryoi, Ugetsu monogatari by UEDA Akinari, Shokoku hyaku monogatari and Taihei hyaku monogatari.

*After dark, participants gather to tell ghost stories. They light a hundred candles and blow out them one by one after telling each story. People believed that when the last candle went out and darkness fell, monsters would appear.

Next

Conclusion/References