明治時代の錦絵の特徴

明治錦絵

このコラムは、電子展示会「錦絵でたのしむ江戸の名所」掲載のコラムを移行・再編したものです。

江戸時代には浮世絵にも検閲があり、主に政治批判、風紀風俗の乱れ、奢侈という3点が取り締まりの対象で、幕府に対する批判が少しでも疑われれば処罰されました。また徳川家や同時代の事件や出来事を題材にすることは禁じられていました。

ここでは、明治時代ならではの特徴を持つ錦絵を紹介します。

錦絵新聞

明治に入り、これまで制限されていたジャーナリズム的要素が浮世絵に加わります。錦絵新聞とは、新聞に掲載された記事を元に事件の一場面を描いたもので、明治7(1874)年に浮世絵師、落合芳幾が初の錦絵新聞『東京日々新聞』を発行します。内容は殺人事件や刃傷沙汰、不倫などのスキャンダルといった、いわゆる三面記事が多く取り上げられました。落合の他に、月岡芳年、豊原国周など当時の有名浮世絵師も新聞社に挿絵を提供するようになりました。

郵便報知新聞 第七百廿九号

日新真事誌 第丗七号

横浜絵

幕末の安政6(1859)年6月2日に横浜が開港すると、寒村だった横浜に国内外から人や物が集まり、港町として発展しました。横浜の繁栄の様子や外国人の生活描写を描いた横浜絵と呼ばれる浮世絵が生まれます。

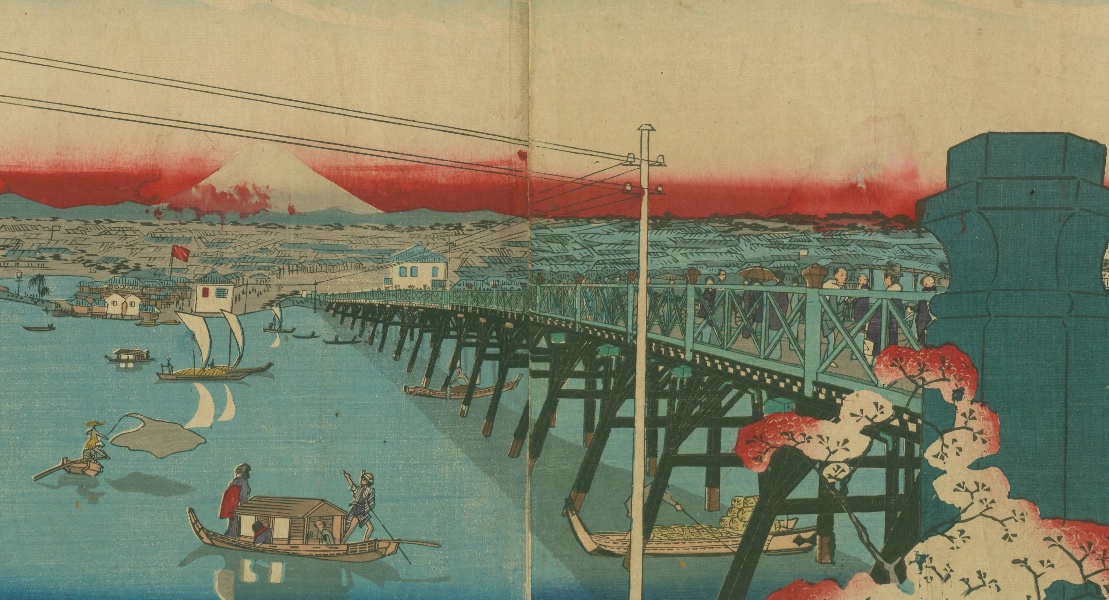

開化絵

明治時代に入ると、文明開化で移り変わる町の様子をテーマとした開化絵が描かれます。洋装・洋髪の日本人、お雇い外国人の設計・指導による洋風建築物、石橋や鉄橋に架け替えられた橋、汽車・鉄道馬車・蒸気船などの開化乗物などが描かれました。

洋装

上野公園での花見の様子です。女性は洋傘を手に、男性はシルクハットをかぶっています。

洋風建築

築地ホテル館は慶応4(1868)年に開業した日本最初の本格的ホテルです。駿河町(現東京都中央区室町)の洋館は、明治7(1874)年に建設された為替バンク三井組(のちの三井銀行)です。

浅草の仲見世の建物は煉瓦造りになりました。

橋

隅田川にかかる両国橋は、明治8(1875)年に西洋風木橋に架け替えられました。富士山の前には電線が通っています。両国橋の北に架かる吾妻橋は、明治20(1887)年に鉄橋に架け替えられました。

工場

小野組築地製糸場は、ケンネル式抱合装置を備えるイタリア式製糸場で、明治4(1871)年8月に開業しました。

富岡製糸場は、明治5(1872)年に設立された日本初の官営模範製糸場です。

鉄道

明治5(1872)年に開業した新橋駅の様子です。蒸気機関車を待つ人々の服装は和装、洋装さまざまです。

明治7(1874)年に開業した大阪駅も描かれています。

馬車・自転車

東海道の起点である日本橋では、人力車、馬車、自転車など様々な乗り物が行き交っています。

博覧会

明治10(1877)年に第1回内国勧業博覧会が開催されました。博覧会開場式を描いた錦絵には、壇上に明治天皇と皇后、左手前には各国公使が描かれています。第3回内国勧業博覧会を描いた上野公園の鳥瞰図では、現在、東京国立博物館がある場所に博覧会会場があり、その右側には蒸気機関車が見えます。

海水浴

海水浴を楽しむ女性たち。水着を着た女性もいます。

江戸城内

江戸時代には禁止されていた江戸城内の様子も明治時代には描けるようになりました。楊洲周延が描いたシリーズものの錦絵『千代田之御表』、『千代田之大奥』では将軍や大奥の年中行事や日常を垣間見ることができます。

千代田大奥(千代田之大奥) 御花見

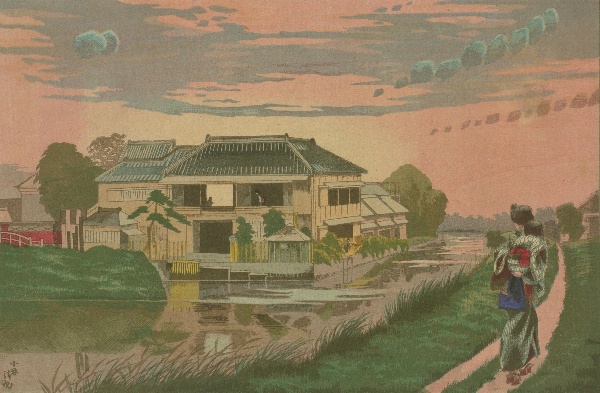

光線画

明治に描かれた錦絵に「光線画」と呼ばれるものがあります。光線画とは西洋絵画の遠近法、陰影法、明暗法といった手法で光を表現した浮世絵で、明治9(1876)年に小林清親によって始められ、版元の松木平吉が名付けたといわれます。清親は明治14(1881)年から光線画を描かなくなりますが、弟子の井上安治は明治22(1889)年に亡くなるまで描き続けました。

品川海上眺望図

赤絵

これまでに見てきたように、明治の錦絵では鮮やかな赤が特徴です。江戸末期になると、ベロ藍やアニリン(赤)、ムラコ(紫)といった人口顔料が輸入され、安くて発色もよいことから多用されるようになりました。輸入顔料により浮世絵の色合いはより鮮明になります。特に明治になると毒々しいまでの赤や紫が目立つようになり、特にアニリン染料を使った赤色が目立つところから赤絵と総称されました。明治初期の錦絵はその鮮やかな色合いからか、現代ではあまり人気がないようです。しかし、野々上慶一は『文明開化風俗づくし : 横浜絵と開化絵』の解説で、「あの刺激的な色彩にこそ、溌溂たる明治の息吹やざわめき、明治らしい匂いを感じ取ることが出来るという見方もある。」としています。

錦絵の衰退

明治初年頃から20年代にかけて、活版や石版といった西洋の印刷技術が続々と日本へ伝わって実用化され、大量印刷が可能になります。明治3(1870)年に『横浜新聞』が活版の日刊紙として発行されました。明治14(1881)年頃からは石版が流行し、明治22(1889)年にはその全盛を迎えます。また、同年には小川一真がアメリカで学んだコロタイプの製版工場を開き、星野錫もアートタイプ(コロタイプに同じ)を日本に紹介しました。明治23(1890)年には堀健吉によって写真亜鉛版の製版法が実用化され、写真が印刷できるようになりました。

発行までのスピードや写実性、価格の面で印刷に劣る錦絵は、徐々に衰退していきます。明治27(1894)年に始まった日清戦争では戦争錦絵の売れ行きがよく、人気が復活したかに見えました。しかし、明治37~38(1904~1905)年の日露戦争では、3色分解や、平版による大量のカラー印刷ができるようになったことや、逓信省発行の戦役記念絵葉書が爆発的に売れて、絵葉書が大流行したことなどからあまり人気が出ませんでした。

明治40(1907)年の『朝日新聞』(10月4日朝刊)の「錦絵問屋の昨今」という記事には「江戸名物の一に数へられし錦絵は近年見る影もなく衰微し(略)写真術行はれ、コロタイプ版起り殊に近来は絵葉書流行し錦絵の似顔絵は見る能はず昨今は書く者も無ければ彫る人もなし」とあり、このころになると錦絵がほとんど出版されなくなった様子がうかがえます。

引用・参考文献

- 鈴木登美, 十重田裕一, 堀ひかり, 宗像和重 編, "検閲・メディア・文学 : 江戸から戦後まで" (新曜社 2012 【UM71-J5】)

- 野々上慶一 編著, "文明開化風俗づくし : 横浜絵と開化絵" (岩崎美術社 1978 【KC16-713】)

- 樋口弘 編, "幕末明治開化期の錦絵版画" (味灯書屋 1943 【733-H448b】)

- 高津孝 編・執筆 et.al, "明治の浮世絵師と西南戦争 : 平成23年度鹿児島大学附属図書館貴重書公開" (鹿児島大学附属図書館 2011 【Y121-J6383】)

関連記事

関連人物

電子展示会「近代日本人の肖像」にリンクします。

こちらもご覧ください

明治錦絵