- Kaleidoscope of Books

- The Lost Tokyo Olympics of 1940

- Chapter 3: The outbreak of war and cancellation of the Olympics

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Japan’s participation in the Olympic Games

- Chapter 2: Tokyo’s bid to host the Olympics

- Chapter 3: The outbreak of war and cancellation of the Olympics

- Chronology

- Conclusion/References

- Japanese

Chapter 3: The outbreak of war and cancellation of the Olympics

The jubilation of Tokyo winning the right to host the 1940 Olympics was short lived. What at first appeared to be a bright future was gradually clouded over until, in July 1938, the planned Tokyo Olympics were cancelled.

In this chapter, we look at the events that led up to the cancellation, the thoughts and actions of those involved in the decision-making process, and the reactions of the athletes affected by the cancellation.

The 1936 Summer Olympics

The Games of the XI Olympiad were held in Berlin during August 1936, immediately following the IOC session at which Tokyo was named host of the XII Olympiad. The Berlin Olympics were a politically charged affair that are sometimes referred to as the “Nazi Olympics.” Although Hitler had expressed a very negative attitude toward hosting the Olympic Games prior to coming into power, having become the Reich Chancellor, he now saw the games as an opportunity to promote the policies and enhance the prestige of Nazi Germany, and to this end, director Leni Riefenstahl was asked to document the Games on film. Entitled Olympia, Riedfenstahl’s documentary was released in two parts: Fest der Völker (festival of nations) and Fest der Schönheit (festival of beauty). These films were praised for their artistic quality and innovative techniques but were also frequently criticized as Nazi propaganda.

The Berlin Olympics attracted a great deal of attention in Japan, because of the successes of Japanese athletes at previous Olympic Games in Los Angeles as well as the IOC’s choice of Tokyo to host of the next Olympics Games.

8) Ed., the XI Olympics Supporters' Association, Dai juichi kai Olympic Taikai Shashin cho: Berlin 1936 (XI Olympics photo collection: Berlin 1936), the XI Olympics Supporters' Association, 1936. [特278-103]

This is a photo book that focuses on the successes of Japanese athletes at the XI Olympics. Japanese athletes were expected to do well in the swimming competition but failed to live up to these high expectations. Nevertheless they continued on their success at the Los Angeles Olympics but winning a good number of medals. Photos of TAJIMA Naoto in the triple jump and MAEHATA Hideko in the breaststroke are included in the book.

The Japanese soccer team faced heavily favored Sweden in its first match. The Swedes took an early two-goal lead and seemed to overwhelm the Japanese in the first half. Using short-pass tactics in the second half, however, the Japanese team recovered and scored three points to score a dramatic upset victory. Many of the local spectators sought autographs from the Japanese players. In spite of this, the Japanese media failed to report extensively on this “miracle in Berlin” at home.

Art competitions were also a feature of early Olympic Games, starting with the 1912 Stockholm Olympics, and included examples of architecture, painting, sculpture, and music. Suzuki Sujaku and Fujita Ryuji were awarded bronze medals in painting at the Berlin Olympics. Art competitions were later abolished after the 14th London Olympics in 1948, due to the difficulties inherent in evaluating the works and the aging of the competitors.

Preparations for the Tokyo Olympics

Preparing for the Tokyo Olympics, a number of programs as well as booklets introducing Japan were published.

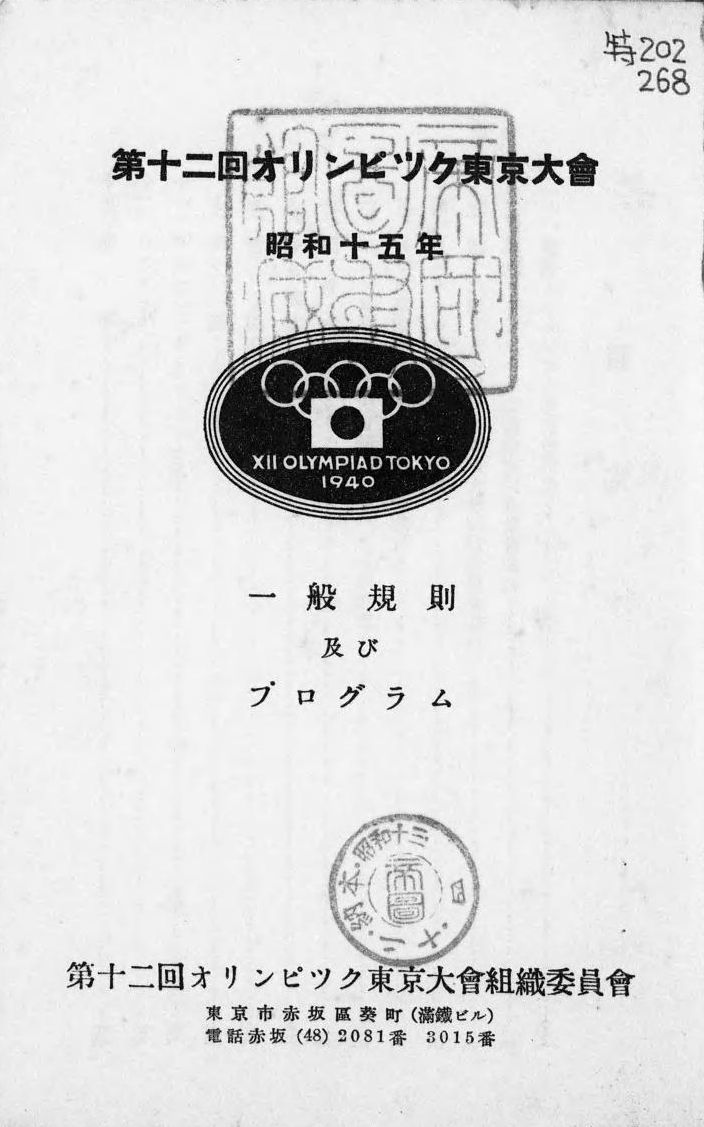

9) Dai juni kai Olympic Tokyo Taikai Ippan Kisoku oyobi Program: Showa 15 (general rules and program of the Games of the XII Olympics in Tokyo), 1940. [特202-268]

This booklet contains a planned program for the 1940 Tokyo Olympics, covering not only track and field or swimming events but also planned exhibitions of martial arts and baseball. And it shows that art competitions were also scheduled to be held in Tokyo. This book was translated into English, French, and German for distribution at the IOC session in 1938.

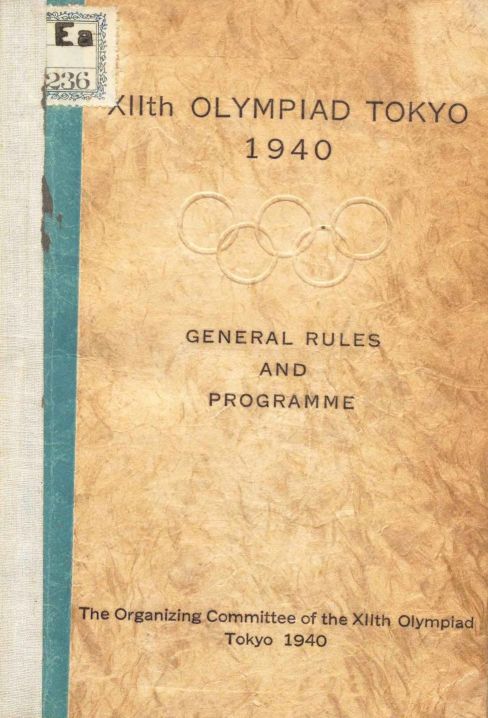

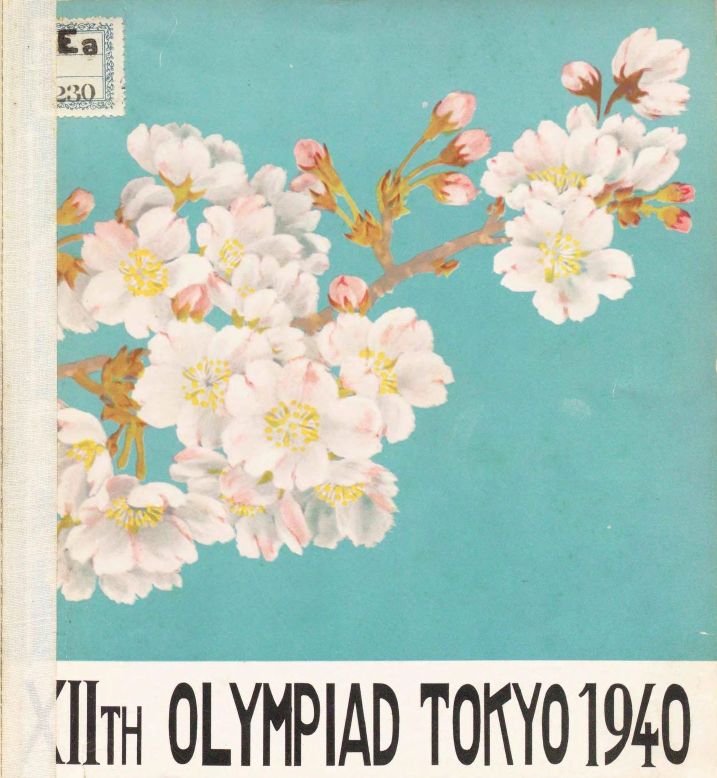

10) XIIth Olympiad Tokyo 1940: olympic preparations for the celebration of the XIIth Olympiad Tokyo 1940, The Organaizing Committee of the XIIth Olympiad Tokyo, 1940, [1938]. [Ea-230]

This booklet in English introduces the Tokyo Olympics and Japan. Liberally illustrated and designed to be visually appealing, it described not just the athletic events and stadiums but also access to Tokyo from all over the world, including public transportation and accommodations in Tokyo. English, French, and German versions were also published and distributed.

At the front of the book is “The Last Message of Baron De Coubertin,” which describes why Tokyo should host the Olympics.

Coubertin passed away in September 1937 without seeing the Tokyo Olympics become a reality.

Domestic criticism of the Olympics

Delays in preparations for the Olympics and an aggravated international situation cast a dark shadow over the early days of 1937. Less than a year after the euphoria of having been selected to host the Olympics, opposition to the games began to surface. According to Dai juni kai Olympic Tokyo Taikai Tokyo shi houkokusho (report on the 12th Olympics in Tokyo from the City of Tokyo) (Tokyo, 1939. [785-25]), KONO Ichiro, a member of the House of Representatives who later served as public minister for the Games of the XVIII Olympics after the war, was one of the first public officials to express criticism. Claiming that it would be impossible to host the Olympics properly amid escalating international tensions, Kono asked Prime Minister and Education Minister HAYASHI Senjuro as well as Foreign Minister SATO Naotake to comment at a meeting of the Lower House Budget Committee on March 20th, 1937. (Dai nanaju kai Teikoku Gikai Shugiin Yosan Iinkai Giroku (Sokki) Dai jugo kai (proceedings of the 15th Lower House Budget Committee during the 70th Imperial Diet) ![]()

This comment became famous as opposition to hosting the Olympics grew due to the international situation. Kono also criticized the Organizing Committee of the Tokyo Olympics for indecisiveness in allowing preparations to fall behind schedule as well as the Mayor of Tokyo for his heavy-handed attitude, thereby providing us with a glimpse of how disorganized things really were.

This comment became famous as opposition to hosting the Olympics grew due to the international situation. Kono also criticized the Organizing Committee of the Tokyo Olympics for indecisiveness in allowing preparations to fall behind schedule as well as the Mayor of Tokyo for his heavy-handed attitude, thereby providing us with a glimpse of how disorganized things really were. With the start of the Sino-Japanese war in July 1937, building materials and other commodities were being carefully controlled in Japan. The National General Mobilization Act and regulations for the control of iron and steel distribution made it more difficult than ever to construct new facilities. The Ministry of Finance proposed that construction of new facilities for the Olympics be abandoned and that existing facilities be used for international exhibitions that were planned as part of the celebration of the 2600th anniversary of founding of the Imperial House. The Organizing Committee naturally protested fiercely. There were even those who thought that Japan should not host the Olympics if there were no choice but to use existing facilities. A plan to construct a new stadium entirely from wood was proposed but was not carried out.

The IOC session in Cairo and the faith of Kano Jigoro

Despite having overcome fierce competition to win the right to host the Olympic Games, Tokyo was susceptible to the impact of a prolonged Sino-Japanese war. China as well as some western nations wanted Japan to forfeit the Olympics, and the number of people who questioned Japan’s ability to actually carry out the games only increased.

Nevertheless, an IOC session held in Cairo during March 1938 formally agreed to hold the Summer Olympics in Tokyo and the Winter Olympics in Sapporo during 1940 thanks to some desperate scheming and persuasion by Kano and others. Kano’s son, Risei, was interviewed after Tokyo was selected to host the 1964 Summer Olympics, and his comments offer some insight into what happened in Cairo. “The session became heavy going because Japan was criticized for engaging in war. My father kept a journal in a black leather notebook that came to me when he died. There is a note dated March 15th that says, ‘We showed firm faith and the decision to hold the Tokyo Olympics was made,’ but all the days for a week before and a week after that are blank. He clearly must have been very busy.” (Yomiuri Shimbun, Tokyo, May 27, 1959, morning edition, p 11 [Z81-16])

In Japan, it was reported that the IOC session in Cairo has resoundingly voted in favor of Tokyo hosting the Olympics. But the truth is that the idea of canceling the Tokyo Olympics and allowing a different country to host the games was also considered. Not only that, but even after the session, the IOC continued to encourage Japan to cancel the games.

11) YOKOYAMA Kendo, Kano Sensei Den (Mr. Kano’s life), Kodokan, 1941. [289-Ka582ウ]

Although some of the books written about Kano Jigoro focus on education and judo, this book is quite interesting, because it delves into other aspects of his life. For example, Chapter 4 of this book, entitled “The Father of Sports,” talks about his accomplishments as an early supporter of sports and the Olympics in Japan as well his activities prior to the IOC Cairo session. It mentions that “He said that plans for the main stadium were not yet finalized and that there was nothing to report. The discussions are likely to be very involved. He left Tokyo saying that he was going to make his point openly and proudly, because he believed Japan to be a major power that was capable of hosting the Olympics, even though he was essentially empty handed … He also said that ‘at the end of the day, you have to stay flexible but be ready to use your best move.’” We can interpret this passage to mean that Kano left for Cairo knowing that all he could do was stick to his belief that Japan could pull it off.

Kano Jigoro passes away without fulfilling his lifelong ambition

Kano just barely succeeded in preventing the cancellation of the Tokyo Olympics but, on his way back from the IOC Cairo Conference, he caught a cold that turned into pneumonia and passed away on May 4, 1938. His sudden death made an impact both at home and abroad, especially among those involved in the Olympics and judo.

A conversation with an American reporter was reported on page 8 of the morning edition of the Asahi Shimbun on May 5, 1938 [Z81-1]. “Mr. Kano achieved his mission at the Cairo session and passed away on his way home. His fate is reminiscent of that of Pheidippides, the Greek messenger who died after running back to inform the Athenians of victory at the Battle of Marathon.” Yet in spite of Kano’s efforts, the Tokyo Olympics were forfeited fewer than three months after his death.

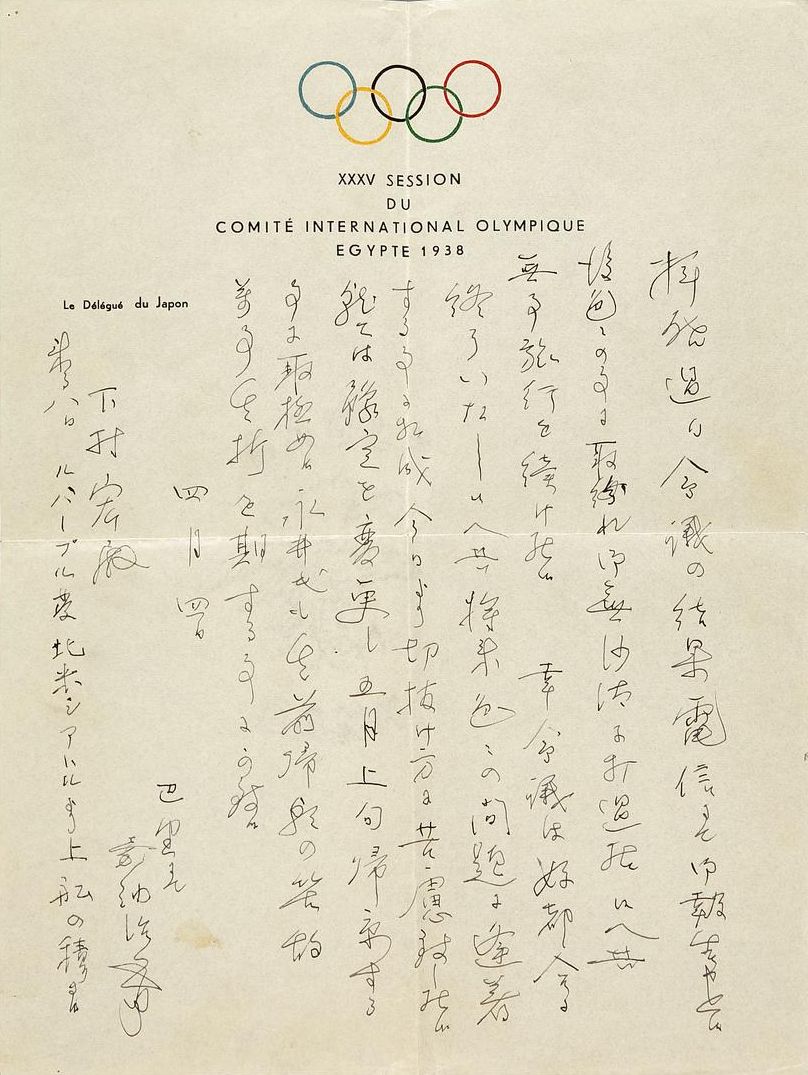

12) Showa 13 nen 4 gatsu 4 ka zuke Shimomura Hiroshi ate Kano Jigoro Shokan (a letter from Kano Jigoro to SHIMOMURA Hiroshi, dated April 4, 1938). [Shimomura Hiroshi Related Document (No. 1) 256]

Kano sent this letter to Shimomura Hiroshi, a member of the House of Peers and chairperson of Japan Amateur Sports Association, a month before he passed away. In it, we can read of his distress caused by the problems that persisting even after he achieved his goals during the IOC Cairo session. Kano passed away on May 4, just a month after he wrote this letter, while returning to Japan.

<Translation>

Dear Sir,

I told you that I would report the results of the recent session by telegraph at a later date, since then have been too busy to follow up on that promise. Nevertheless, I continue to travel home safety. The session finished auspiciously, but there are many problems yet to be resolved, and I am struggling to deal with them now.

We changed our schedule to return to Tokyo in early May.

Mr. Nagai* will also return to Japan at that time, which I think is good timing.

April 4

Paris, From Kano Jigoro

To Mr. Shimomura Hiroshi

On the 8th, we will embark from Le Havre to Seattle, in North America.

*NAGAI Matsuzo, executive secretary of The Tokyo Organizing Committee, who later served as a member of the IOC.

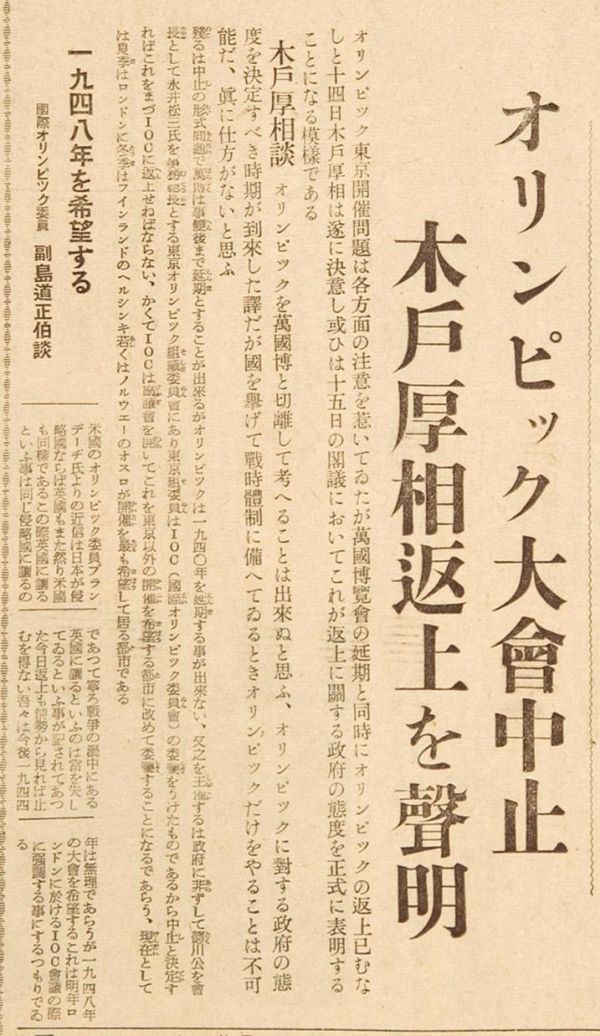

Soejima Michimasa and the decision to cancel the Olympics

A deteriorating international situation, including the intensification of the Sino–Japanese war, the control of raw materials, and a wave of calls both at home and abroad for the Olympics to be canceled made it impossible to avoid making a decision any longer. On July 15, 1938, the Cabinet decided to cancel both the Tokyo and the Sapporo Olympics.

In theory, the cancellation should have been the decision of the Tokyo Organizing Committee, but in fact it was led by the Government. With the passing of Kano Jigoro on his way back to Japan as well as with the chairperson of the Tokyo Organizing Committee and IOC member TOKUGAWA Iesato suffering from an illness, it fell to Soejima Michimasa, who worked for the Government as well as held a position on the IOC, to take a stand on whether or not to hold the games.

The following excerpt from an article in the Asahi Shimbun asserts that Soejima was aware of the potential for the cancellation a full year before the decision was made. “[Soejima] demanded that the Government make an immediate decision. Having accepted the opportunity to host the Olympics in 1940, Japan should stick to its commitment irrespective of the international situation, because should Japan cancel the games, it would take a year and a half for England or two years for Finland to make preparations to host the Olympics.” (Asahi Shimbun, Tokyo, August 31, 1938, evening edition, p. 2 [Z81-1])

It is ironic that, during a series of discussions with Prime Minister KONOE Fumimaro and other concerned parties, Soejima became a central figure in the push to cancel the games, despite his previous role in negotiations with Mussolini during the selection process.

The IOC was promptly informed of the cancellation, and numerous telegrams were sent in response. The content of these responses were published in the report issued by the Organizing Committee after the cancellation. (Report of the Organizing Committee on Its Work for the XIIth Olympic Games of 1940 in Tokyo until Their Cancellation, The Organizing Committee of the XIIth Olympiad, 1940. [54-123]) Some were sympathetic to Japan, while others condemned the cancellation and questioned Tokyo’s suitability as host for any future Olympics.

The impact of the cancellation on the athletes

Needless to say, the cancellations of the 1940 Tokyo and Sapporo Olympics as well as the subsequent 1944 Games deprived numerous athletes of the opportunity to participate in the Olympics in their prime. History is full of “ifs,” and there is no question that the lives of many athletes would have been quite different has the prolongation of the war not caused the cancellation of the Tokyo and Sapporo Olympic Games.

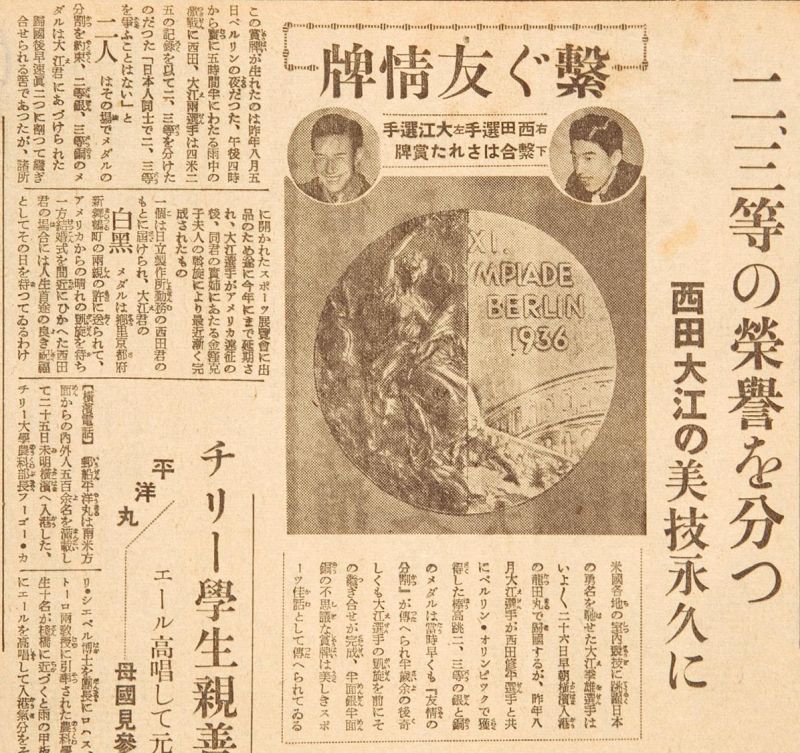

Oe Sueo and the medal of friendship

OE Sueo took part in the Berlin Olympics as a pole vaulter and finished in third place, just behind NISHIDA Shuhei. Although both men cleared the height of 4.25 m, Nishida was awarded second place, because he jumped first. Oe not only very much looked forward to the Tokyo Olympics, he also felt a strong sense of responsibility. During a lecture he gave to a Nihombashi youth organization, he said “We must win in international competitions. Our national character is reflected in the morale of our athletes.” (Oshima Jukuro, Olympics shashin shi taikan: dai juni kai Olympics Tokyo shouchi kinenjigyou (Olympic photo history book: the 12th Tokyo Olympics bidding memorial project). [748-122])

Oe was drafted into the army in 1939 and died at the front in 1941. Some newspapers reported that Oe and Nishida had divided their Olympic medals in half to create two medals that were each half silver and half bronze, thereby reflecting the fact that they had shared second and third places at the Berlin Olympics. In the postwar period, these medals were featured in magazines and on television as well as in elementary school textbooks as “friendship medals.”

Inada Etsuko, Japan’s youngest Olympic athlete

At the tender age of 12 years old, INADA Etsuko took part in the figure skating competition at the Garmisch-Partenkirchen Winter Olympics in Germany in 1936, and finished in tenth place as Japan’s youngest ever Olympic athlete. Sonja Henie, winner of that event, remarked that “Inada’s era will arrive before long.” Having won the All Japan Championship five times, she was considered a favorite, and everyone in Japan was looking forward to her performance at the Sapporo Olympics, but the cancellation of the 1940 Olympics robbed her of her chance. She returned to the world stage for the first time in 15 years in 1951, competing in world championships, where she failed to impress and slipped to a low rank. The difference in technique and costume at the world level was overwhelming.

Some 52 years after the Tokyo Olympics were cancelled, ITO Midori finally won an Olympic medal in figure skating for Japan by taking the silver at the Albertville Winter Olympics in 1992.

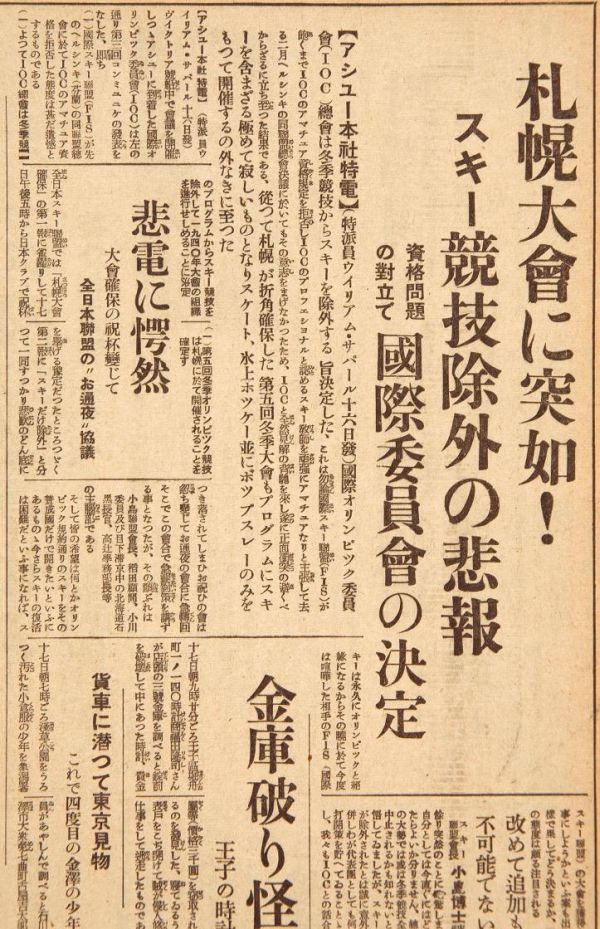

Column: A dilemma for the Sapporo Olympics—FIS and amateur rules

Typically, the host nation for the Summer Olympics also hosts the Winter Olympics that same year. Thus, when Tokyo was awarded 1940 Summer Olympics at the IOC Berlin session in 1936, the Winter Olympics should have been awarded to Sapporo at the same time. But uncertainty over Japan’s ability to prepare adequately meant that the Winter Olympics were not awarded until the IOC Warsaw session in June of the following year and again reconfirmed at the IOC Cairo session a year after that the decision.

The decision was not without controversy, however, because the suggestion was made that the Winter Olympics be held without a ski competition.

This controversy was due to a feud between the IOC and the International Ski Federation (FIS). IOC rules at the time did not allow professional athletes to participate in the Olympics Games, out of an ideal attributed to the ancient Olympics. Yet in modern times, many world-class skiers work as instructors during the winter. The IOC notified the FIS that ski instructors would not be allowed to compete in the Olympics due to their status as non-amateurs. Naturally, the FIS objected, because they did not regard ski instructors to be professional athletes.

This same issue caused problems for the 4th Garmisch-Partenkirchen Winter Olympics in 1936, but a ski competition was held due to the FIS making a concession. As the rift between the IOC and the FIS widened, however, at last they reached an impasse, and the ski competition was excluded from the Sapporo Olympics.

Although Winter Olympics now feature a great many events, significantly fewer than now were planned at that time, and many said that it made no sense to hold the Winter Olympics without a ski competition. Baron INADA Masatane, chairperson of Ski Association of Japan, and others familiar with the planning for the Sapporo Olympics scrambled to find a compromise that would allow a ski competition to be held, but their efforts came to nothing when the Olympics were cancelled.

Next

Chronology