Conclusion: The Olympics in Postwar Japan

After giving up the 1940 Olympics due to intensification of the Second Sino-Japanese War, Japanese society was completely ravaged by the Pacific War. After rebuilding its economy, however, and achieving rapid postwar reconstruction, sports also regained their popularity. Watching sports became a national obsession, and the success of Japanese athletes helped heal the wounds of the past. The world records of FURUHASHI Hironoshin—the “Flying Fish of Fujiyama,” the world title in boxing of SHIRAI Yoshio, Rikidozan’s wrestling performances, and the development of Nippon Professional Baseball all contributed. And at the same time, many Japanese athletes performed brilliantly in the Olympics. Although unable to participate the 14th London Olympics of 1948, Japan returned in time for the 15th Helsinki Olympics in 1952, where Japanese athletes showed great progress in gymnastics and wrestling as well as continued success in track and field and swimming, in which Japanese athletes were successful in the prewar Olympic Games.

Finally, in 1964, Japan hosted the Summer Olympics in Tokyo and in 1972 the Winter Olympics in Sapporo. Although it took an additional 24 years to make Japan’s dream of hosting the Olympic Games in Tokyo a reality, the victory of Japan’s women volleyball team, nicknamed “The Oriental Witches,” is legendary. At these same games, Judo first appeared an official sport. Although the Japanese team dominated throughout, they were shocked by Dutch judoka Geesink’s upset victory over KAMINAGA Akio in the open weight class.

At the Sapporo Olympics, the “Hinomaru Hikotai” (rising sun squadron) of KASAYA Yukio, KONNO Akitsugu and AOCHI Seiji took all three medals in the 70-meter ski jump competition.

In 1998, Japan hosted the Winter Olympics for a second time in Nagano, where once again the Japanese jumpers dominated.

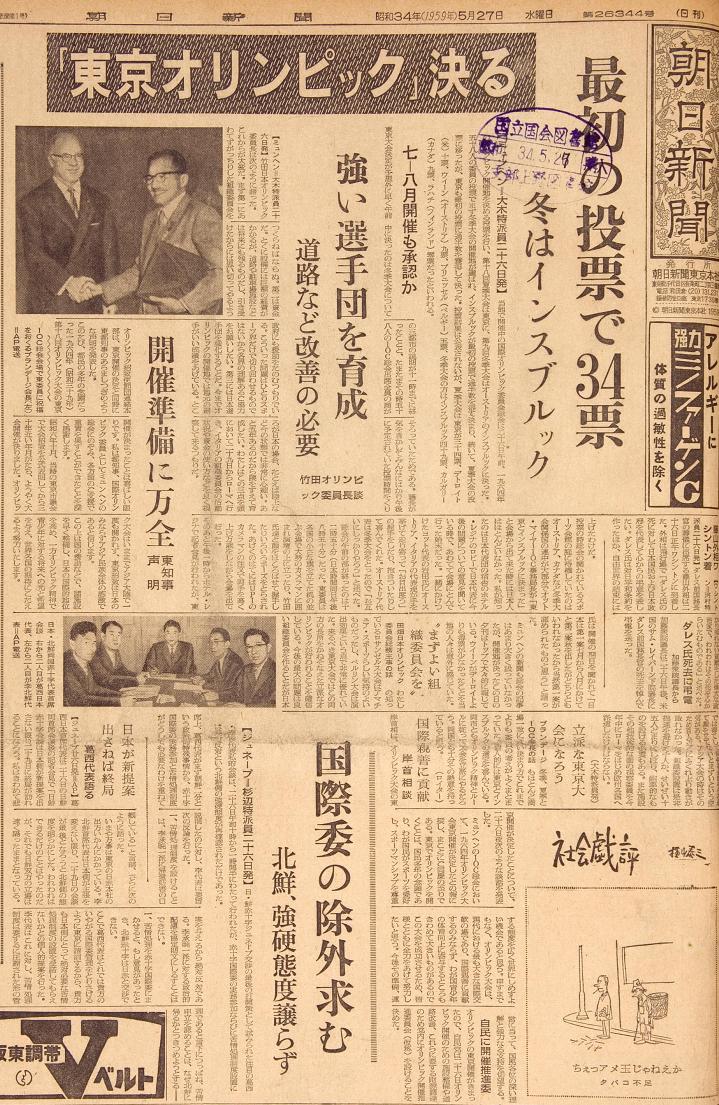

Tokyo and other Japanese cities continued to bid for the Summer Olympics during the 1980s and 1990s, but none were successful until September 2013, when Tokyo awarded the 2020 Olympics and Paralympics. Much has changed in Japan and in the world in the 80 years since the lost Tokyo Olympics. What will we see in Tokyo in 2020?

References

- Ikei Masaru, Kindai orimpikku no hiro tachi, Nippon hoso shuppan kyokai, 2004.7. [FS6-H7]

- Oda Mikio, Kin medaru, Waseda daigaku shuppanbu, 1972. [FS21-3]

- Oda Mikio, Rikujo kyogi waga jinsei, Besuboru magajin sha, 1991.9. [FS33-E149]

- Sakaue Yasuhiro, Kenryoku souchi toshiteno supotsu, Kodansha, 1998.8. [FS22-G48]

- Shitteru tsumori?! 10 (Kokoro yasashiki shorisha tachi), Nihon terebi hosomo, 1993.4. [GK11-E29]

- Takeda Kaoru, Orimpikku zen taikai, Asahi shimbunsha, 2008.2. [FS27-J2]

- Ed., Nihon orimpikku akademi, Orimpikku jiten, Horupu shuppan, 1982.1. [FS2-47]

- Nihon ginko chosa tokei kyoku, Meiji iko oroshiuri bukka shisu tokei Jokan, Nihon ginko, 1987.9. [DT792-E1]

- Nihon taiiku kyokai 75 nenshi, Nihon taiiku kyokai, 1986.6. [FS4-83]

- Nihon taiiku kyokai・Nihon orimpikku iinkai 100 nenshi 1911→2011 part 1, Nihon taiiku kyokai, 2012.3. [FS4-J104]

- Hamada Sachie, “Senzen nihon no orimpikku”, Komyunikeshon kagaku, vol.32, 2010. [Z6-B329]

- Homma Shuko, “Hitomi Kinue to nihon no orimpikku mubumento no hatten”, Taiiku kenkyujo kiyo, vol.29, December, 1989. [Z7-297]

- Ed., Zennihon taiiku shinkokai, Seika ha higashi he Koki 2600 nen no orimpikku taikai ni sonaete, Meguro syoten, 1937. [725-68]

- Ed., Dai 12 kai Orimpikku Tokyo taikai soshiki iinkai, Dai 12 kai Orimpikku Tokyo taikai soshiki iinkai houkokusyo, 1939. [779-51]

- Kano Jigoro, “Orimpikku taikai to kokusai kankei”, Nihon to sekai, vol.124, February, 1937. [雑56-50イ]

- Tahara Junko, Dai 12 kai orimpikku kyogitaikai(Tokyo taikai)no chushi ni kansuru rekishiteki kenkyu, [UT51-94-L33]

- Ikei Masaru, “Berurin orimpikku no seijiteki riyo”, Nihon gaiko no gendaishiteki tenkai, 1994. [UT51-94-J377]

- Hirai Tadashi, “Rifuenshutaru--Hitora・Gorin soshite Afurika—Kiken womo haramu sono miwakutekina koseibi”, Asahi janaru, vol.1114, June, 1980. [Z23-7]

- Arai Emiko, “Berurin no kiseki”, Ushio, vol.488. October 1999. [Z23-13]

- Yoshida Hiroshi, “Kindai orimpikku ni okeru geijutsu kyogi no kosatsu—Geijutsu to supotsu no kyozon (fu) kanosei wo megutte”, Bigaku, vol. 57, no.2, 226, Autumn, 2006. [Z11-34]

- Suzuki Yoshinori, Houo techo, Seibido, 1938. [754-162]

- Kajiwara Hideyuki, Orimpikku henjo to manshujihen, Kaimeisya, 2009.9. [FS27-J24]

- Ogawa Katsuji, “Sapporo taikai henjo made”, Sukii nenkan, Zennihon sukii renmei, 1938. [572-145]

- Ed., Tokyo shi, Dai 12 kai Orimpikku Tokyo taikai Tokyo shi hokokusho, Tokyo shi, 1939. [785-25]

- Ooshima Tokuro, Orimpikku shashin shi taikan:Dai 12 kai orimpikku Tokyo taikai shochi kinen jigyo, Meiji tenno shotoku hosankai, 1938. [748-122]

- Oe Motohiko, “Gimban no joo・Etchan”, Maru, vol.7, no.3, March, 1954. [Z2-171]

- “Supotsu kai retsuden sono 13・Inada Etsuko”, Asahi Shimbun (Tokyo), March 7, 1983, Morning Edition, p.18. [Z81-1]

External links

- Japan Olympic Committee, The Olympic Movement and Kano Jigoro (Last access date: August 4, 2021)

- Japan Center for Asian Historical Records National Archives of Japan, Tokyo orimpikku, 1940 nen~Maboroshi no tokyo orimpikku he~ (Last access date: August 4, 2021)