- Kaleidoscope of Books

- The Dawn of Modern Japanese Architecture

- Chapter 2: Competitions - Contests by Architects

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Birth of Architects - Those Who Learned at the Imperial College of Engineering

- Chapter 2: Competitions - Contests by Architects

- Chapter 3: Tour of Buildings - From the World of Landmark Guidebooks

- References

- Japanese

Chapter 2: Competitions - Contests by Architects

Owing to the efforts of Josiah Conder and his students, buildings designed by Japanese architects began to increase after the foundation of the Imperial College of Engineering, and the architectural design competition for the office building of the Government-General of Taiwan in 1908 became the first of those in which many architects could take part to attempt to win first prize. All architects were treated equally in competitions whether they were famous or not. Unlike the past when there were court architects and carpenters under the patronage of the privileged classes, these competitions could be regarded as democratic attempts for architects to freely establish their own independent status through their own ability. Though not all competitions succeeded in implementing this philosophy, we can find that they took pains to decide how to carry out judgement or the application requirements in order to get better results.

This chapter looks at some unique buildings from those days and illustrates the process of making decisions about architectural plans through competitions with some winning designs.

The Office Building of the Government-General of Taiwan

The beginning of authentic architectural design competitions was that for the office building of the Government-General of Taiwan, the project for which started in 1908. Though some people claimed that the building should be designed by the technicians of the Government-General of Taiwan, Lord GOTO Shimpei, who had also served as Chief of Home Affairs of Taiwan, promoted an architectural design competition and donated 30 thousand yen (equivalent to 33 million yen today) to it because he believed that the more prize money offered, the more serious the applicants would be and the better the proposals. The competition invited TATSUNO Kingo, TSUMAKI Yorinaka, and so on as judges and was supposed to give 30 thousand yen to the first prize winner, 15 thousand yen to the second and 5 thousand yen to the third. Without a winner of the first prize, NAGANO Uheiji won the second prize, who was a technician of the Bank of Japan and designed its Otaru branch building with Tatsuno and OKADA Shinichiro. In 1919, the office building of the Government-General of Taiwan was built, the design of which was based on Nagano’s proposal and modified by MORIYAMA Matsunosuke working for the government.

The Competition for the National Diet Building - a Long-term Argument over the Plan

The Temporary Wooden National Diet Building

Based on the imperial instruction in 1881 to establish the National Diet, the Extraordinary Construction Bureau for government office buildings, which included the Diet Building, was set up in the Cabinet in 1886. With the goal of presenting an image as a civilized country by constructing a government quarter appropriate for the capital, and to gain an advantage in negotiating over the revision of unequal treaties, the bureau invited 2 German architects, Wilhelm Böckmann and Hermann Ende, to draw up a plan. Though Böckmann proposed a magnificent plan in Baroque style, Ende later cut back its scale because it would take a huge sum of money to construct buildings according to the original plan. For the Diet, they decided to build a temporary wooden building in order not to miss the deadline for the opening of the Diet, and it was finally completed on November 24, 1890, a day before the convocation of the first Imperial Diet. The Extraordinary Construction Bureau was abolished in the same year. From then to 1936, when the regular Diet Building was completed, the temporary wooden building was used despite having to be rebuilt two times because of fires.

Tsumaki vs. Tatsuno

For over 15 years since the Imperial Diet started meeting in the temporary building, several proposals for the construction of a permanent Diet Building were not accepted due to issues such as cost. It was 1906 when the time became ripe. The bill for the construction of the new National Diet Building was introduced in the House of Representatives, followed by research on foreign parliament buildings and surveying the provisional site. Some said that a competition should be held for this construction, but Tsumaki, Director General for Special Constructions in the Ministry of Finance, who had already played a major role in this project, objected and advocated a plan being formed by a council of authorities, arguing that if a competition was held, excellent architects could not take part in forming a plan because they would have to be judges. (See Eizen Kanzaikyoku ed. “Teikoku gikai gijido kenchiku no gaiyo (summary of the Imperial Diet)” [KA272-E15]) As a result, the project was led by bureaucrats at first. This is an episode which represents that there were not many architects at the time.

It was Tatsuno who opposed that and promoted the competition. In 1908, Tatsuno and other architects submitted a written suggestion calling for a competition. Two years later, based on the suggestion, the Society of Architecture (now known as the Architectural Institute of Japan) proposed a competition to the Preparatory Committee for National Diet Building Construction set up in the Ministry of Finance, but only six members out of 21 voted for it. The government stood in opposition and commented that no leading architects could enter the competition if they were appointed as the judges (see Nihon Kenchiku Gakkai (editor), “Kindai nihon kenchikugaku hattatsushi” [NA25-G24]). This story means that the method proposed mainly by the officials under the leadership of Tsumaki overpowered the committee. But the project was postponed again when the Katsura Cabinet resigned.

Carrying out the Competition

After Tsumaki died in 1916, Tatsuno and his group proposed a competition again. In June 1918, a special bureau for the National Diet Building construction project was set up in the Ministry of Finance, and then the competition opened in September, as Tatsuno had desired for a long time. He himself joined as a judge. The requirements placed no limitation on style, but stated that the plan had to be dignified as appropriate for the National Diet, and a ground plan made by the bureau was provided for reference. The first prize was ten thousand yen (equivalent to 5.4 million yen today). There were 2 rounds in the competition, and out of a total of 118 proposals submitted by February 1919, twenty passed the first screening. Nonetheless, the judges don’t seem to have been satisfied with them. They sent an instruction which asked those who qualified to present a well-planned and bold revision for the second round, regardless of their original proposals.

In the second round in September 1919, WATANABE Fukuzo, a technician of the Ministry of the Imperial Household, won the first prize. Tatsuno himself had died in March without seeing the competition through to the end. The actual blueprint was made by the bureau referring to the works of the finalists.

When the works of the finalists were put on view, many of them were criticised for not going beyond existing architectural concepts. In particular, the architect SHIMODA Kikutaro petitioned the Imperial Diet to change the blueprint, protesting that it was just copying the Western style. Shimoda left Tatsuno's class at the Industrial College of the Imperial University of Tokyo just before graduation and moved to the United States. He joined the Page Brown architects’ office there. When the office won the competition for the California State Pavilion at the Chicago World's Fair, he was appointed to supervise its construction, and became the first Japanese architect licensed by the American Institute of Architects. Coming back to Japan in 1898, he went through a hard time without any academic posts or corporate architectural advisory positions, since he had left Tatsuno's class. The petition from Shimoda, who was outside the mainstream Japanese architectural world at that time, was of a rebellious spirit and finally led to a discussion in the Diet session. He advocated the style of “Teikan Heigoshiki Isho (lit. Emperor's crown installed design),” representing Japanese style incorporating the merits of different Western styles. This is said to be the origin of Teikan style, synonymous with Japanesque and oriental tastes.

The construction of the new Diet Building started in 1920 and was completed in 1936. It is still in use today.

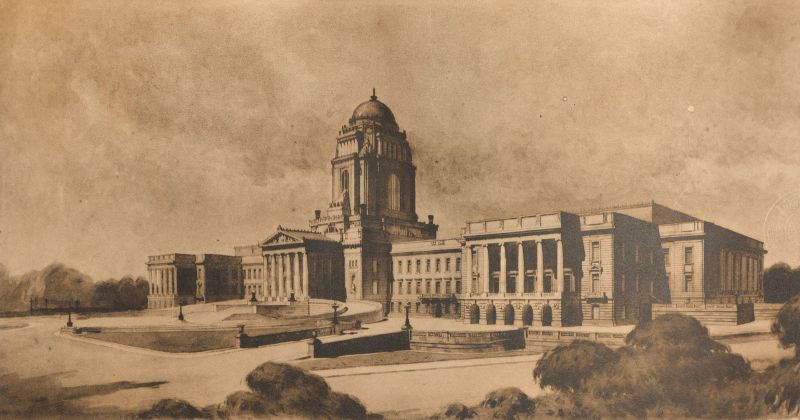

4) Koyosha ed. Giin kenchiku isho sekkei kyogi zushu (Catalogue of the design competition for the Diet Building), Koyosha, Taisho 9 (1920) [422-13]

This book contains the 4 proposals which passed the second screening, including the one which won the first prize, and the 20 which passed the first. The latter are published under false names like “Hinode” or “Sagarifuji”, which were used to hide the author’s names in the judging process.

The first-prize proposal shows a building with a dome on top, though there is a square pyramid on the actual building.

The Competition for Osaka City Public Hall – Challenge for a New Judging Method

The construction of Osaka City Public Hall (now the Osaka City Central Public Hall, also called Nakanoshima Public Hall) started with IWAMOTO Einosuke, a broker at the Osaka Stock Exchange, who donated 1 million yen (equivalent to over 10 billion yen today) to the City of Osaka to make use of his property gained from stock investments for the public sake in 1912. The city decided to hold a competition with a first prize of 3 thousand yen (equivalent to 3.1 million yen today). Tatsuno, who engaged in planning the competition as an architectural consultant, adopted a new method, in which 17 active architects were selected (4 of them declined) to mutually judge each other’s proposals. As a result, the proposal by OKADA Shinichiro, 30 years old at that time, was selected unanimously. He had graduated from the Industrial College of the Imperial University of Tokyo and designed the building of the Otaru branch of the Bank of Japan. It seems that Okada’s design skill shown in these buildings made Tatsuno select him even with less experience than the other participants.

With a glorious Neo-Renaissance* design, putting a big arch on the top of the main entrance of the building, Okada came to be regarded as one of the leading architects. The construction of the building started in 1913 after some modifications to the design by Tatsuno and Kataoka’s office, and it was completed 5 years later in 1918. But Iwamoto, who devoted a large sum of his private money to the project, did not see the building completed, as he committed suicide due to an investment loss in 1915. It is said that he would never ask the City of Osaka to return even some of his donation of one million yen regardless of the advice from people around him after the loss.

The building is popular among citizens of Osaka, and after the city announced plans to demolish it in 1971, a public campaign succeeded in completely preserving the building. After the completion of the preservation and restoration work of the building in 2002 and its registration as an Important Cultural Property in the same year, it remains in use today.

*Neo-Renaissance: The classic architectural style which blossomed in Italy in the 14th to 15th century is called the Renaissance style. The Neo-Renaissance style arose in Europe in the first half of the 19th century.

5) Osaka-shi Kokaido Kensetsu Jimusho Osaka-shi kokaido shinchiku sekkei shimei kensho kyogi obo zuan (Catalogue of the design competition for Osaka City Public Hall), Kokaido Kensetsu Jimusho, Taisho 2 (1913) [407-61]

Table of contents of Osaka-shi kokaido shinchiku sekkei shimei kensho kyogi obo zuan (Catalogue of the design competition for Osaka City Public Hall)

It contains the proposals from the 13 designated architects for the competition for Osaka City Public Hall.

As Tatsuno wrote in the preface that he believed that the competition could accomplish great things by involving all the brilliant architects in Japan, having a unique judging method, and having a good result, he must have been satisfied with the new judging method and its outcome. Behind Tatsuno’s decision to adopt the method, which he himself described as unique, it is assumed that he took pains to gather both the best judges and best participants, considering the opposition to the competition for the construction of the Diet Building.

The Competition for the Tokyo Imperial Museum – Expression of Japanism

In 1923, the main building of the Tokyo Imperial Museum was heavily damaged by the Great Kanto Earthquake. The coronation of Emperor Showa in 1928 was used as an occasion to start the reconstruction project, and a competition for the rebuilding was decided to be held.

In those days, Teikan style buildings with Japanism or Orientalism influences were advocated for and built in opposition to modern Western style buildings, with the rise of nationalism in Japan. The Teikan style involves structures with a Japanese tiled roof on top of a European reinforced concrete building. The museum set up a committee to design and research which style to use for the construction, which took almost a year. As a result, the competition which was announced in 1930 required participants to adopt “an Oriental style based on Japanism” because of the character of the museum holding many Oriental antiques. The prize was 10 thousand yen (equivalent to 7.6 million yen today). Out of 273 proposals presented by the deadline in the following year, 5 proposals were awarded, and the first-prize proposal by WATANABE Hitoshi, who had worked for the Construction Division of the Ministry of Communications, included a Japanese-style gable roof.

Based on the actual design used by the Ministry of Imperial Household, the building was under construction from 1932 to 1937. It is now used as the main building of the Tokyo National Museum.

6) Tokyo teishitsu hakubutsukan kenchiku sekkei kensho nyusen zuanshu (Selected designs of the competition for the Tokyo Imperial Museum), Nihon Kenchiku Kyokai, 1931 (Showa 6) [特254-563]

Cover of Tokyo teishitsu hakubutsukan kenchiku sekkei kensho nyusen zuanshu (Selected designs of the competition for the Tokyo Imperial Museum)

This book contains the first to fifth winning proposals for the competition for the Tokyo Imperial Museum, and other works with honorable mentions. To meet the criteria of “an Oriental style based on Japanese taste,” all proposals look like Teikan style with Japanese traditional roofing. It demonstrates the trend of architectural design in Japan at that time.

Other Competitions

Besides the 4 competitions described in this chapter, there were also other competitions at that time. You can see the works for other competitions collected by the National Diet Library in the following page.

Next Chapter 3:

Tour of Buildings