- Kaleidoscope of Books

- The Dawn of Modern Japanese Architecture

- Chapter 1: Birth of Architects - Those Who Learned at the Imperial College of Engineering

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Birth of Architects - Those Who Learned at the Imperial College of Engineering

- Chapter 2: Competitions - Contests by Architects

- Chapter 3: Tour of Buildings - From the World of Landmark Guidebooks

- References

- Japanese

Chapter 1: Birth of Architects - Those Who Learned at the Imperial College of Engineering

The history of modern architecture in Japan began around the period between the late Edo era and the early Meiji era. Though those who engaged in architecture had already existed, it was not until the early Meiji era, when Western technology and culture were introduced, that architects who professionally designed and supervised architecture appeared.

In this chapter, we will introduce the circumstances of the dawn of modern architecture in Japan before competitions began, looking at the people who founded the base of modern architecture along with the education of the Imperial College of Engineering.

The Establishment of Kogakuryo and the Imperial College of Engineering

It was Kogakuryo (a school of technology) and its successor, the Imperial College of Engineering, both under the Ministry of Engineering, that pioneered professional education of architecture in Japan. The Ministry of Engineering was a central administrative organ which was established to promote the modernization of industry and supervise government enterprises. Under it, Kogakuryo and the Imperial College of Engineering trained students engaging in industry.

Kogakuryo was established in 1871 (Meiji 4) to educate technocrats belonging to the Ministry of Engineering. In 1877 (Meiji 10), due to the reorganization of the Ministry of Engineering, Kogakuryo changed into the Imperial College of Engineering, and took charge of engineering education until 1885 (Meiji 18) when the Ministry of Engineering was abolished.

1) Kyu kobu daigakko shiryo hensankai ed., Kyu kobu daigakko shiryo (Historical materials of the former Imperial College of Engineering), Toranomonkai, 1931 (Showa 6) [292-88]

This book by Toranomonkai, an association of graduates of the Imperial College of Engineering, compiles the history of the College from the establishment of Kogakuryo to its reorganization into the College of Engineering of the Imperial University in 1886 (Meiji 19).

There were two types of students in Kogakuryo: students with a government scholarship and privately financed students. The former students were excused the fees, and instead obligated to work in the Ministry of Engineering for 7 years after the graduation. All students were able to get a government scholarship as a rule when Kogakuryo opened, but starting in 1879 (Meiji 12), all students had to be financed privately except for a few superior students who received a government scholarship.

When Kogakuryo opened, many of the teachers were foreign specialists. Dyer, who served as an assistant principal, was paid 660 yen monthly. The fact that his salary was as high as that of a high-level government official shows us how well the teachers were treated and how they were expected to do a good job.

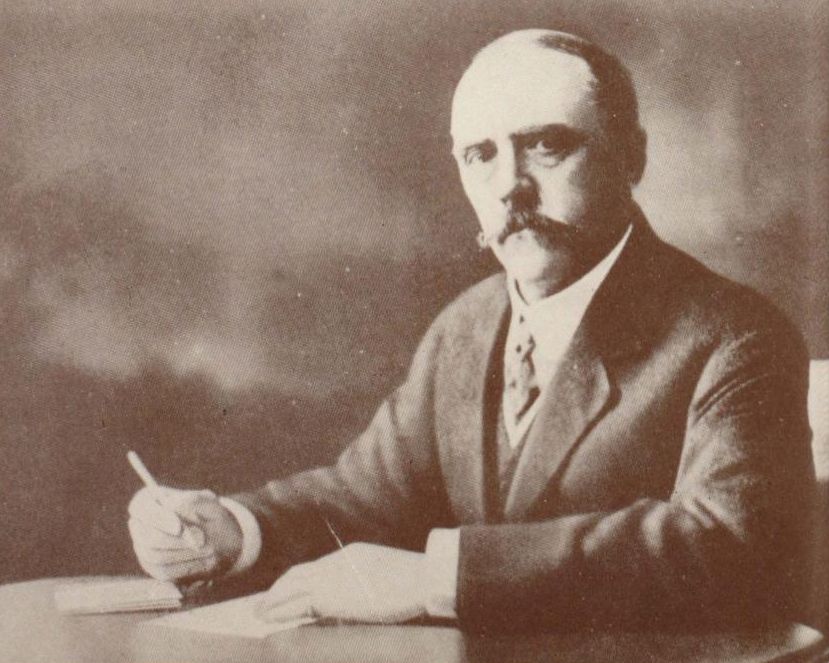

Benefactor of Japanese Architecture, Conder

It was Josiah Conder, one of the foreign specialists employed by the government, who played an essential role regarding the education of architecture in the Imperial College of Engineering. Born in London in 1852, Conder studied architecture at the University of London. He won the Soane Prize in a design competition hosted by the Royal Institute of British Architect, and became a promising architect. In 1877 (Meiji 10), he came to Japan, accepting an invitation by Japanese government to teach architecture at the Imperial College of Engineering, at only 25 years old . He also belonged to the Ministry of Engineering as an advisor to the Bureau of Building and Repairs and designed many buildings such as the Imperial Museum (the former main building of the Tokyo National Museum), Rokumeikan, and Hokkaido Development Commissioners’ sale and reception rooms (the former head office of the Bank of Japan).

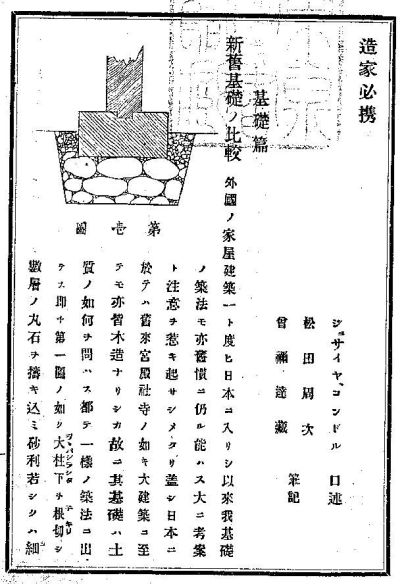

2) Josiah Conder Zouka hikkei (A handbook for building), KATO Ryokichi, 1886 (Meiji 19) [34-96]

This is a practical guide about architecture, which was stated orally by Conder and dictated by MATSUDA Shuji and SONE Tatsuzo. Each article in it was originally published serially on the journal of Kougakukai (now the Nihon Kougakukai, the Japan Federation of Engineering Societies), which was organized by graduates of the Imperial College of Engineering and said to be the first academic society in Japan. We can guess what architecture was like during the time of the Imperial College of Engineering from this material. This book consists of two sections, foundations and paving stones, the former of which shows examples of pile foundations of actual buildings such as Rokumeikan.

Conder’s Students

The first batch of graduates who studied under Conder in the Department of Building of the Imperial College of Engineering included TATSUNO Kingo, KATAYAMA Tokuma, SONE Tatsuzo and SATATE Shichijiro. Though other foreign specialists employed by the Ministry of Engineering, including Boinville and Diack, were in charge of the education at Kogakuryo before Conder, it is said to have consisted mainly of practical training and not to have been systematic. At the College of Engineering, Conder gave systematic lectures as well as involving the students in architecture which he was designing to let them learn by practicing. Each of his students played an active role after graduating from the college.

After having retired from the front line of education, Conder designed many residential buildings and guest houses, such as IWASAKI Hisaya’s residence.

TATSUNO Kingo

TATSUNO Kingo graduated from the Department of Building at the top of the class in 1879 (Meiji 12) and went to England the following year on a government grant to study at the University of London and the William Burgess architect office, which his teacher Conder had worked at. A year after coming back to Japan in 1883 (Meiji 16) and working at the Bureau of Building and Repairs in the Ministry of Engineering, he became a professor of the Imperial College of Engineering in place of Conder. Though he temporarily retired along with the abolition of the Ministry of Engineering in 1887 (Meiji 18), he took a position as professor at the Imperial University when it was founded the following year. In the same year, the Zouka Gakkai, now the Nihon Kenchiku Gakkai (Architectural Institute of Japan), was established, which Tatsuno joined as a major early member and served as chairperson of for a long time. After he retired in 1902 (Meiji 35), he became active in nongovernmental circles.

It is said that Tatsuno wanted to design three buildings in his youth: the central bank, the central station and the Diet Building. Later, he actually designed the central bank—the Bank of Japan—and the central station—Tokyo Station. With regard to the Diet Building, when the plans for construction were made around 1907 (Meiji 40), Tatsuno insisted on holding an architectural design competition in opposition to the opinion of TSUMAKI Yorinaka, who had been Tatsuno’s student in the Imperial College of Engineering and was the key figure of the Ministry of Finance on this matter.

3) TATSUNO Kingo and KASAI Manji, Kaoku kenchiku jitsurei (Examples of house buildings). The picture of the 1st volume Suharaya, 1908 (Meiji 41) [404-54]

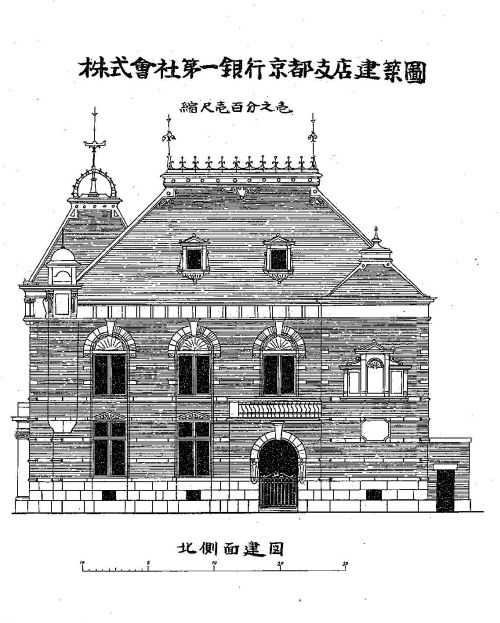

In this book, we can see the contract forms, regulations and directions used in the Tatsuno-Kasai office, an architectural design office which was established by TATSUNO Kingo and Kasai Manshi in Osaka in 1903 (Meiji 36). We can also see instructions, estimates and plans for four buildings managed by the office.

It also contains one of Tatsuno’s main works after leaving public office, the plan for the Kyoto branch of Daiichi Bank (see the picture to the right). We can see the building with white lines on the red bricks, which was called “Tatsuno style”.

KATAYAMA Tokuma

After graduating from the Imperial College of Engineering, KATAYAMA Tokuma started his career as a palace architect when he took part in the construction of the Meiji Palace at the Bureau of Construction of the Imperial Palace. Since he designed notable buildings like the Imperial Kyoto Museum (now the Kyoto National Museum) and Hyokei-kan of the Imperial Tokyo Museum (now the Tokyo National Museum), he is sometimes admired as one of the three great architects of the Meiji era , along with TATSUNO Kingo and TSUMAKI Yorinaka. It can be said that the Crown Prince’s Palace (now the State Guest House or Akasaka Palace) is the pinnacle of his career. This magnificent building embodies the essence of Neo-Baroque* architecture. It shows the designer’s attempt to incorporate traditional Japanese culture into Western style architecture, with a roof with a design of armored samurai.

*Neo-Baroque style: Baroque style is an architectural style which uses combinations of various complicated shapes. It started in Italy in the 16th century and spread all over Europe from the 17th century to the 18th century. The Neo-Baroque style is a revival of the Baroque style which started in France in the late 19th century.

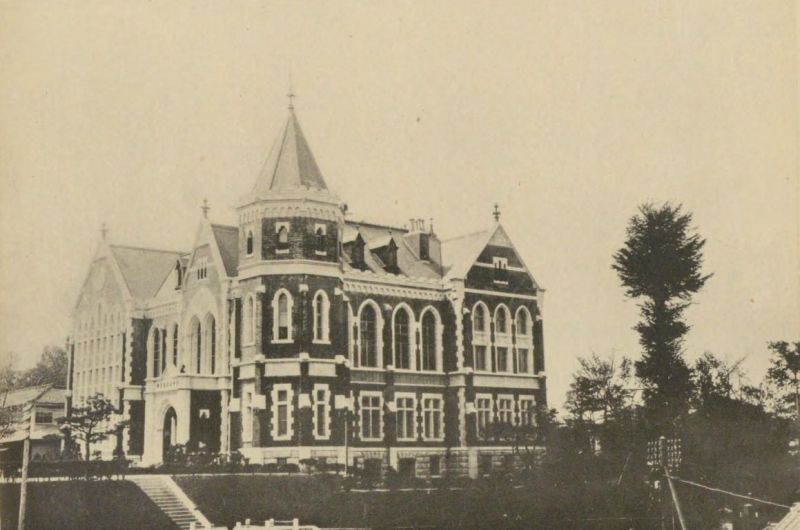

SONE Tatsuzo

The oldest student who studied in the Department of Building under Conder, SONE Tatsuzo also studied together with Tatsuno at the school of Western learning, Taikoryo, which was established in Karatsu-han (Karatsu domain) by TAKAHASHI Korekiyo. After graduating from the Imperial College of Engineering and serving as an assistant professor at that school, he started designing architecture related to the navy. In 1890 (Meiji 23), he entered the Mitsubishi company and supervised the construction of the Mitsubishi Ichigokan building, which was designed by Conder. From then on, he made a great effort to construct buildings in a business district called “Iccho London” in Marunouchi. After he left Mitsubishi in 1906 (Meiji 39), he established the Sone-Chujo architect office with CHUJO Seiichiro in 1908 (Meiji 41). The Keio University library, designed by Sone and Chujo in 1912 (Meiji 45), retains its graceful exterior made of bricks and granite.

SATATE Shichijiro

SATATE Shichijiro worked on the construction of post offices all over Japan in the Ministry of Communications and designed the building for the Japanese datum of leveling. In his later years, he became an advisor to Nippon Yusen and designed its Otaru branch. The building is known as the site of the Japan-Russia border demarcation meeting after the conclusion of the Treaty of Portsmouth.

TSUMAKI Yorinaka

The Department of Building of the Imperial College of Engineering produced 20 graduates before being absorbed into the Imperial University. Tsumaki Yorinaka, who is said to be one of the key persons related to the problem of the construction of the Diet Building and the biggest rival of TATSUNO Kingo, entered the Imperial College of Engineering in 1878 (Meiji 11) and studied under Conder; however, he quit college in 1882 (Meiji 15). He was then admitted to Cornell University in America and received a Bachelor of Architecture degree before coming back to Japan in 1885 (Meiji 18).

After coming back to Japan, Tsumaki started his career in Tokyo. The following year he joined the Special Bureau for Construction, which was established by INOUE Kaoru as part of a project to construct numerous government offices, and was sent to Germany until 1889 (Meiji 22) to study design at the Ende-Beckman architect office which had designed the central governmental office district. After the plan for centralizing government offices was largely scaled down due to political reasons, the special bureau was abolished and Tsumaki moved to the Ministry of Home Affairs, which took over the plan, and then to the Ministry of Finance. From 1901 (Meiji 34), when he took a position as chief of the maintenance and repair department, he had great influence on the construction of government offices.

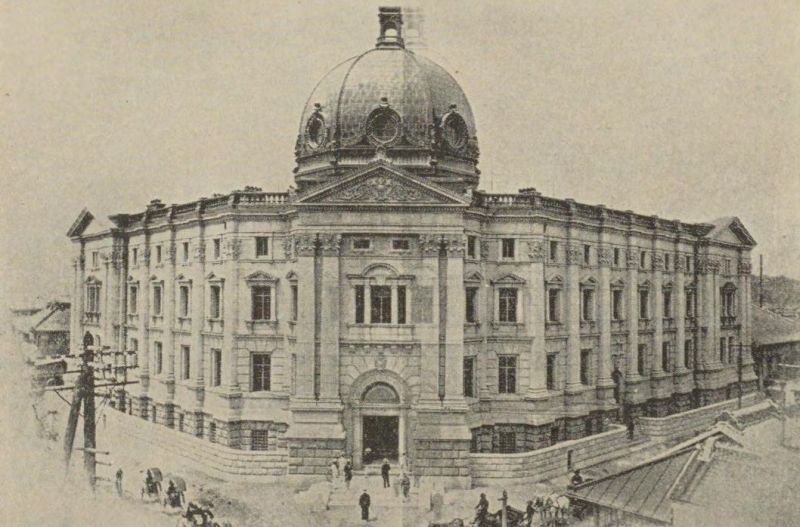

The Yokohama Specie Bank (now the Kanagawa Prefectural Museum of Cultural History), completed in 1904 (Meiji 37), is said to be Tsumaki’s representative work. He also designed the Shinko Wharf Bonded Warehouse, which is now known as the Yokohama Red Brick Warehouse.

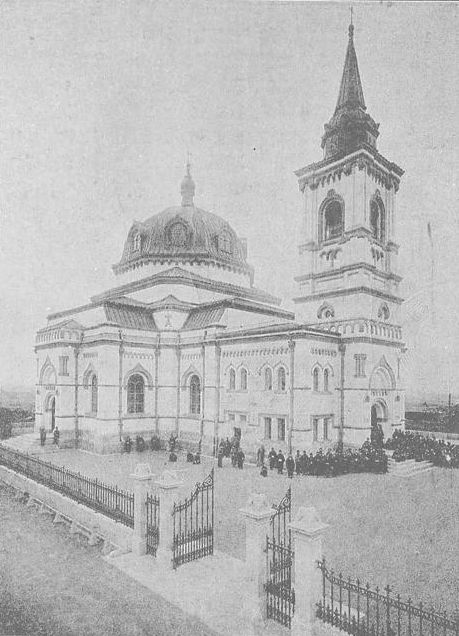

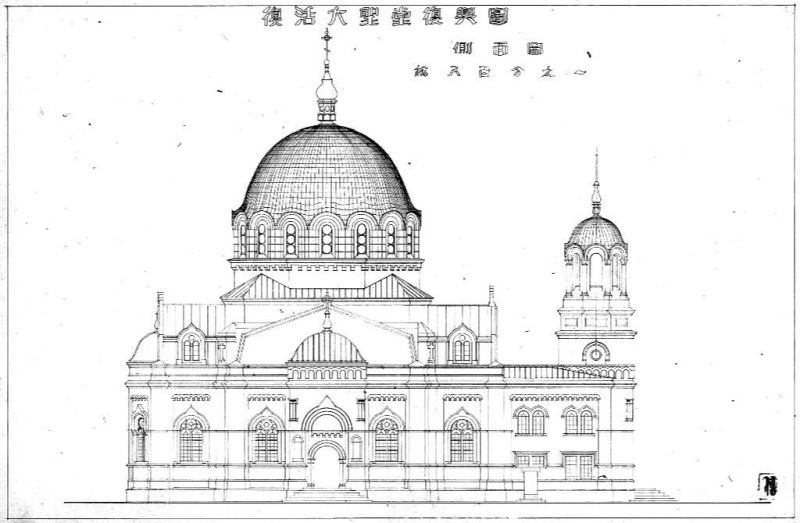

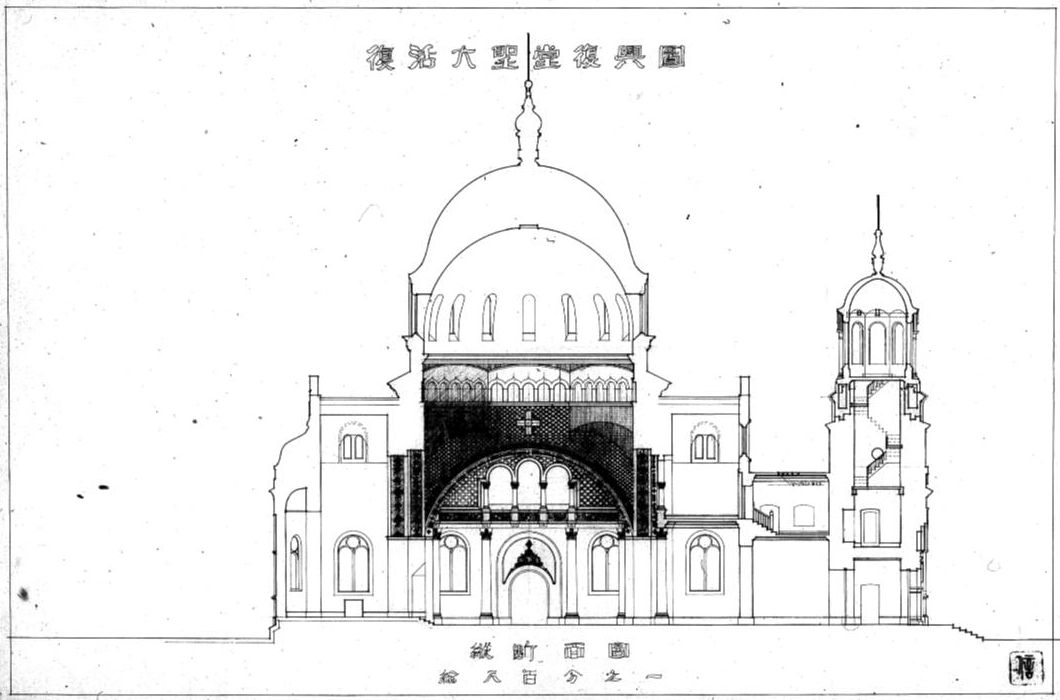

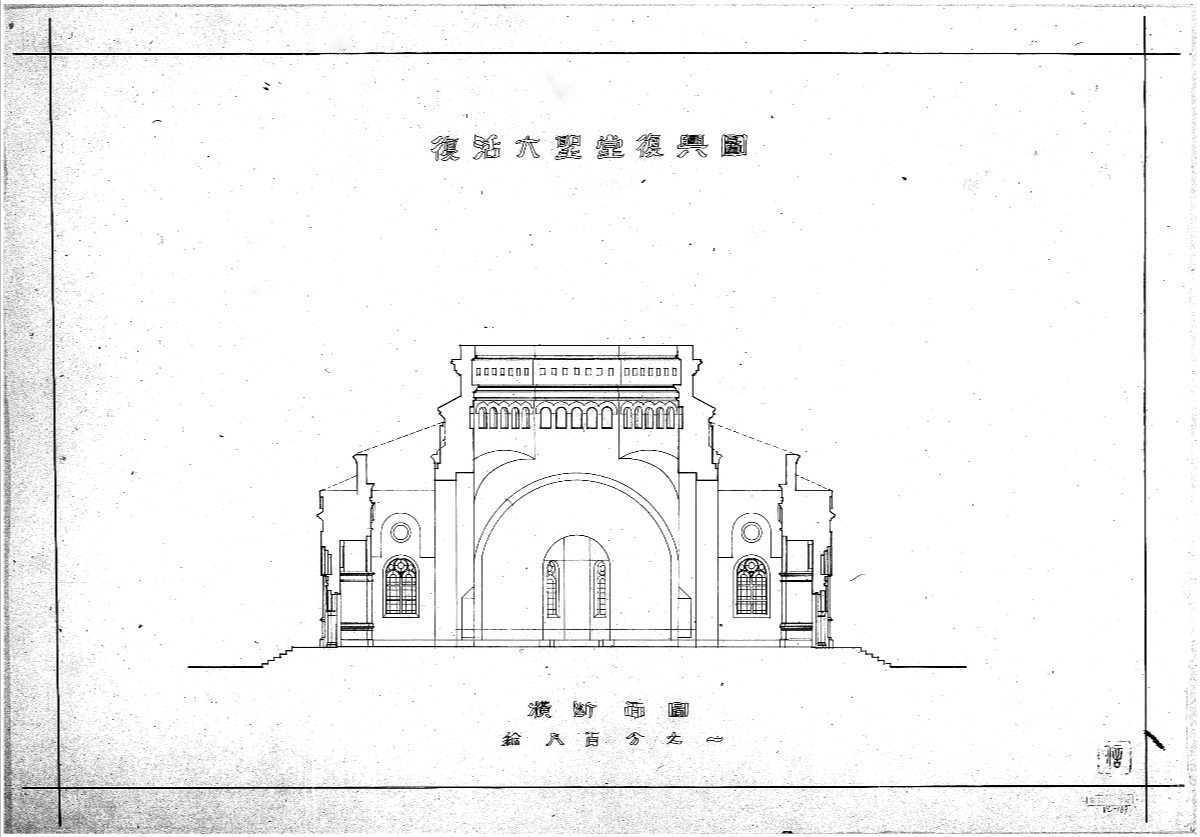

Column: St. Nicholas Church just after completion

Holy Resurrection Cathedral (St. Nicholas Church), standing on a hill in Surugadai, is the biggest Orthodox church in Japan. Based on the original design by Russian architect Michael Shchurupov, Conder made the final design. The construction of the Byzantine revival* cathedral was started in 1884 (Meiji 17).

Completed 7 years later in 1891 (Meiji 24), the cathedral was popularly known as St. Nicholas Church after Nikolay Kasatkin, who had made great efforts to contribute to its construction.

St. Nicholas Church was seriously damaged in the Great Kanto Earthquake in 1923 (Taisho 12): Its 40-meter bell tower collapsed, and due to the subsequent fire, the dome also collapsed and the wooden part burnt down. It was reconstructed between 1927 (Showa 2) and 1929 (Showa 4) based on plans by OKADA Shinichiro, who later designed the Meiji Life Building. Though its structure was strengthened with reinforced concrete and the shape of its dome and bell tower changed at that time, most of its walls made of bricks were kept the same as when it was originally built.

The National Diet Library holds an album of original designs by the brothers OKADA Shinichiro and Shogoro. It contains the reconstruction plans for St. Nicholas Church (see the picture below) and original designs of famous buildings such as the Kabukiza and Meiji Seimei-kan.

*Byzantine Revival style (Neo-Byzantine style): An architectural style which revived the Byzantine style in the latter half of the 19th century, using features such as domes and arches. (The Byzantine style is an architectural style which developed in the Eastern Roman Empire. Its distinctive features are domes and arches. The exterior of buildings are simple, but the interior is decorated with icons made of mosaic, fresco, etc.)

Next Chapter 2:

Competitions