- Kaleidoscope of Books

- Dawn of Mountaineering - Mountains and People in Modern Japan

- Chapter 1: New-style mountain climbing

Chapter 1: New-style mountain climbing

In Japan, after opening the country to the world, a new form of mountain climbing appeared.

Foreign mountain climbers wrote about their travels around the mountains in Japan. These books conveyed the appeal of Japanese mountains to more foreigners. Amid the tide of modernization, women's mountain climbing and mountain climbing for research and study also began.

In the first chapter, we will introduce this new style of mountain climbing.

Climbing mountains by foreigners

In the 18th century, literary works such as Rousseau's Julie ou la nouvelle héloïse depicted the beautiful nature and scenery of the Alps, which caused trekking at the foot of a mountain to become popular. Before long, some climbers started aiming to climb high mountains.

Many Westerners who came to Japan after the opening of the country also loved mountain climbing. We would like to introduce three famous names among them: Rutherford Alcock, Ernest Satow, and William Gowland.

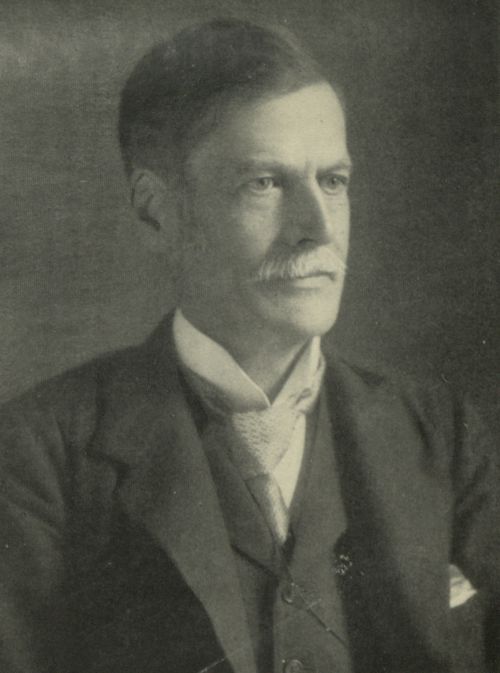

Rutherford Alcock (1809-1897)

Rutherford Alcock was the first British minister to Japan and is believed to be the first foreigner to climb Mt. Fuji.

Born into a family of doctors, Alcock studied medicine in London and Paris and was posted to Spain and Portugal to work as an army surgeon. However, the illness he suffered during that time left him paralyzed in both hands, and he abandoned his career as a doctor and entered the Foreign Office.

After serving as a consul in various parts of China, he came to Japan in 1859 as the first consul general. He was promoted to the rank of envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary in 1860. He returned to the U.K. on a temporary paid leave but stayed in Japan for about three and a half years until 1864. Records of the period of his stay before returning to the U.K. are compiled in The capital of the Tycoon : a narrative of a three years' residence in Japan [A-72](![]() The full text is available in the Internet Archive. See also Japanese translation version : Taikun no Miyako (大君の都) [210.58-cA35o2-Y]).

The full text is available in the Internet Archive. See also Japanese translation version : Taikun no Miyako (大君の都) [210.58-cA35o2-Y]).

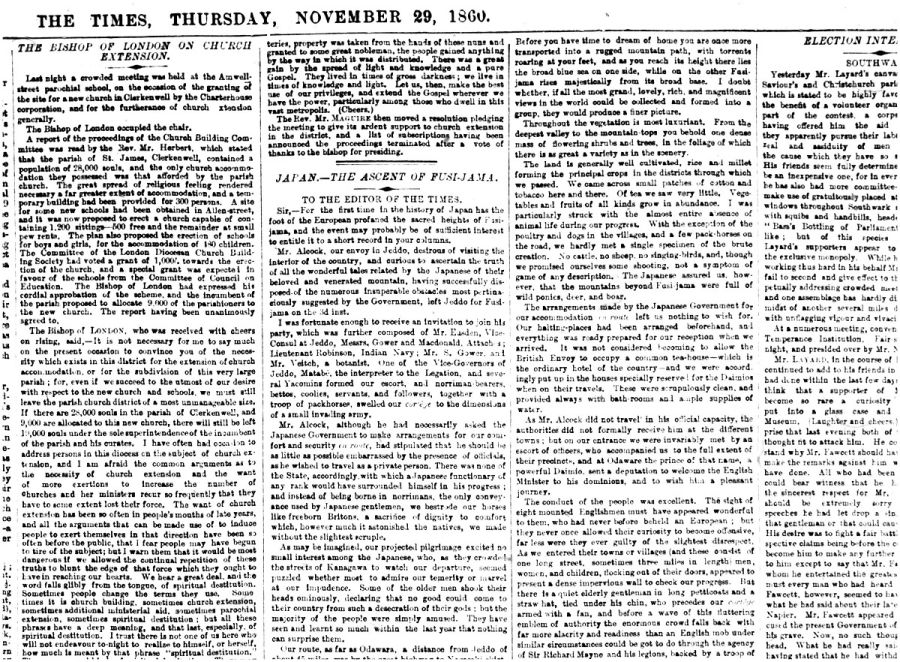

1) “Japan―the Ascent of Fusi-jama,” The Times, November 29, 1860 [YB-F3]

Alcock climbed Mt. Fuji, on July 26, 1860. This article, published in the British newspaper The Times, describes the journey of a reporter who accompanied him on the ascent of Mt. Fuji. As for the reason why Alcock wanted to climb Mt. Fuji, he was curious to see if what people said about Mt. Fuji, which Japanese people love and respect, is true.

Alcock at the summit

“Having visited the temple we proceeded to the highest point of the crater; here Mr. Alcocks, standard-bearer, unfurled the British flag, while we fired a Royal salute in its honour, his Excellency setting the example by discharging the five barrels of his revolver into the crater, and the rest following till 21 guns had been fired. We then gave three cheers, sang ‘God save the Queen,’ and finished by drinking ‘the health of Her Gracious Majesty’ in champagne, iced in the snows of Fusi-jama, to the utter amazement of the Japanese, who had never before seen such startling religious ceremonies.”

Alcock encountered Japanese culture when he was studying in Paris, and he seems to have had a deep knowledge of Japan before he visited. Chapter 20 of The capital of the Tycoon: a narrative of a three years' residence in Japan mentions that Engelbert Kaempfer's Nihonshi (日本誌, original title : Geschichte und Beschreibung von Japan) [GB391-G93] describes Mt. Fuji, "which in beauty, perhaps, hath not its equal." It suggests that Alcock had the habit of reading books on Japan.

However, the Mt. Fuji climb was not carried out solely out of interest in Japanese culture. Another purpose for the climb was that they wanted to check the right of diplomats and consuls to travel freely in Japan was actually protected, as stipulated in the Anglo-Japanese Treaty of Amity and Commerce signed in 1858.

Ernest Mason Satow (1843-1929)

Ernest Satow, an Englishman, came to Japan in 1862 as a lower-ranking official in charge of interpreting. He stayed in Japan for a total of 25 years, working his way up to the position of minister to Japan.

The following is the story of how Satow decided to go to Japan. One night, when Satow was a student, he came home to one of his older brothers reading Lawrence Orifant's Narrative of the Earl of Elgin’s Mission to China and Japan [951.037-O47n](![]() full text available at the Oxford Google Books Project), which the brother had borrowed from the library. After casually taking the book in hand, Satow was captured by its attractive writing style and vivid illustrations. After reading the book, he became interested in heading for the Far East. Soon after, he found a notice on the campus recruiting students as interpreters in China and Japan, applied for it, and passed the selection examination. He became an interpreter at the Consulate in Japan.

full text available at the Oxford Google Books Project), which the brother had borrowed from the library. After casually taking the book in hand, Satow was captured by its attractive writing style and vivid illustrations. After reading the book, he became interested in heading for the Far East. Soon after, he found a notice on the campus recruiting students as interpreters in China and Japan, applied for it, and passed the selection examination. He became an interpreter at the Consulate in Japan.

At the age of 19, his dream came true. Satow came to Japan and traveled all over the country. During that time, he climbed Mt. Fuji, Mt. Ontake, Mt. Akadake, Mt. Asama, Mt. Akagi, Mt. Koshin, and the mountains of the South Alps. Based on this experience, he published A handbook for travellers in central & northern Japan [A-51](![]() The full text is available in the Internet Archive.) in collaboration with A.G.S. Hawes, a retired naval officer. The publisher, Murray, was famous for publishing travel guides, but this was the first travel guide about Japan. It was used by a large number of foreign visitors to Japan for about 40 years, from the first edition issued in 1881 to the final 9th edition addendum issued in 1922. This book introduces a variety of recommended travel routes. For example, on Route 8, "From the Tokaido to Kofu by the temples of Minobu", many mountain names are listed including Mt. Shichimen, Mt. Nakashirane, Mt. Notoridake, Mt. Ainodake, Mt. Hoozan, and Mt. Kitadake. Of course, it also introduces climbing Mt. Fuji as one of the routes.

The full text is available in the Internet Archive.) in collaboration with A.G.S. Hawes, a retired naval officer. The publisher, Murray, was famous for publishing travel guides, but this was the first travel guide about Japan. It was used by a large number of foreign visitors to Japan for about 40 years, from the first edition issued in 1881 to the final 9th edition addendum issued in 1922. This book introduces a variety of recommended travel routes. For example, on Route 8, "From the Tokaido to Kofu by the temples of Minobu", many mountain names are listed including Mt. Shichimen, Mt. Nakashirane, Mt. Notoridake, Mt. Ainodake, Mt. Hoozan, and Mt. Kitadake. Of course, it also introduces climbing Mt. Fuji as one of the routes.

Satow's second son, TAKEDA Hisayoshi, later became one of the founders of the Japanese Alpine Club.

William Gowland (1842-1922)

William Gowland came to Japan in 1872 at the request of the new Meiji Government to mint coins in the Mint as a chemist, and stayed in Japan until 1888. He was interested in art and archaeology and deepened his research into Japanese culture after coming to Japan. He has been called "the father of Japanese archaeology" because he visited various ruins and published his results in papers.

An avid walker, Gowland climbed many mountains in Japan, but in 1878 he became the first foreigner to climb Mt. Yarigatake. In A handbook for travellers in central & northern Japan edited by Ernest Satow, Gowland wrote about mountains. He described the Hida Mountains area as "The most considerable in the Empire, and might perhaps be termed the Japanese Alps." This is the first use of the phrase "the Japanese Alps."

Acceptance of female climbers

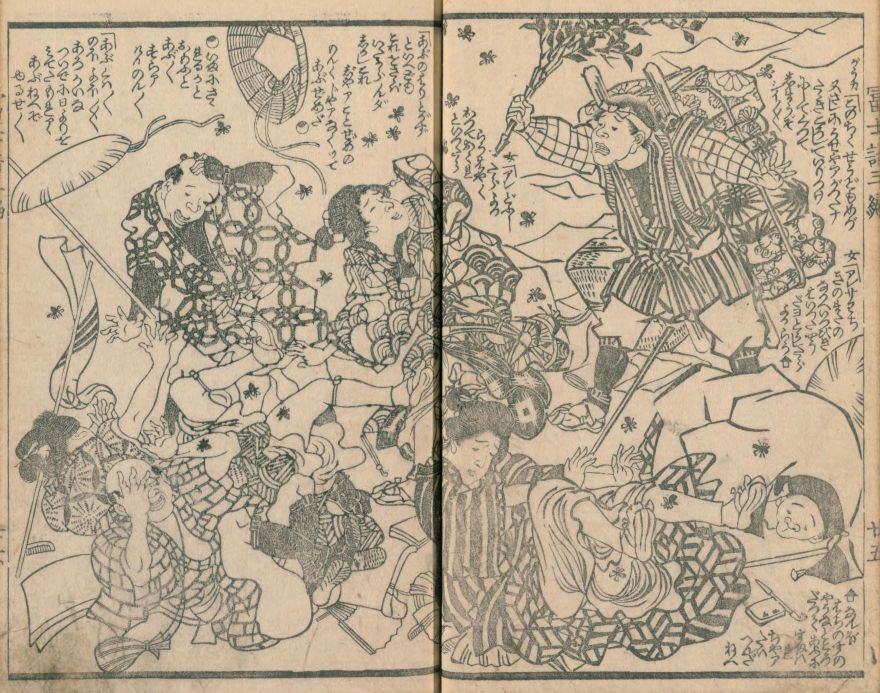

One of the major changes seen in mountain climbing in the early Meiji period is the appearance of women in mountains. In many cases, the centers of Shugendo (Japanese mountain asceticism) and Mountain Buddhism had been inaccessible to women, and this tradition was maintained until the Edo period. However, in order to attract more visitors to temples and shrines near trailheads, it was necessary to allow women to climb mountains, so the idea of allowing women to climb mountains gradually spread. For example, women were allowed to climb up to the eighth station of Mt. Fuji in 1860, the Koshin no Goennen (庚申の御縁年) year (a memorial year once every 60 years). In anticipation of the popularity of this event, gesaku (light literature) writer KANAGAKI Robun depicted men and women climbing mountains in Kokkei Fuji Mode (滑稽富士詣, A humorous pilgrimage to Mt. Fuji) [京乙-75].

Also, foreign women's mountaineering also accelerated the trend to allow women to climb mountains. In September 1867, Harry Smith Parkes, the second British envoy, climbed Mt. Fuji with his wife, Fanny. It seems to be the first time for a foreign woman to climb the mountain. Not only did the attendant at the trailhead not complain about her climbing Mt. Fuji, they also submitted an application to the authorities to allow Japanese women to climb Mt. Fuji other than the Koshin year because of this precedent of a foreign women climbing.

In March 1872, the "ban on women" was lifted in many mountains by Dajokan (the Grand Council of State) Proclamation No. 98, "Temples and shrines must abolish bans on women and allow mountain climbing." Thus, the number of female climbers gradually increased.

When MATSUURA Takeshiro, an explorer who had been climbing mountains since the end of the Edo period, visited Mt. Tonomine in Nara Prefecture in 1885, he wrote a poem describing the sight of women on the mountain, "It used to be a place where women were forbidden, but now it is different. Women wearing a red apron at inns with lanterns, called Hananaka-ya and Momiji-ya, touted for guests to take a rest and stay. So, the times are changing in the mountains as well."(Itsuyu Shoki (乙酉掌記) [特67-482])The taboo against women in the past seemed to have gradually faded.

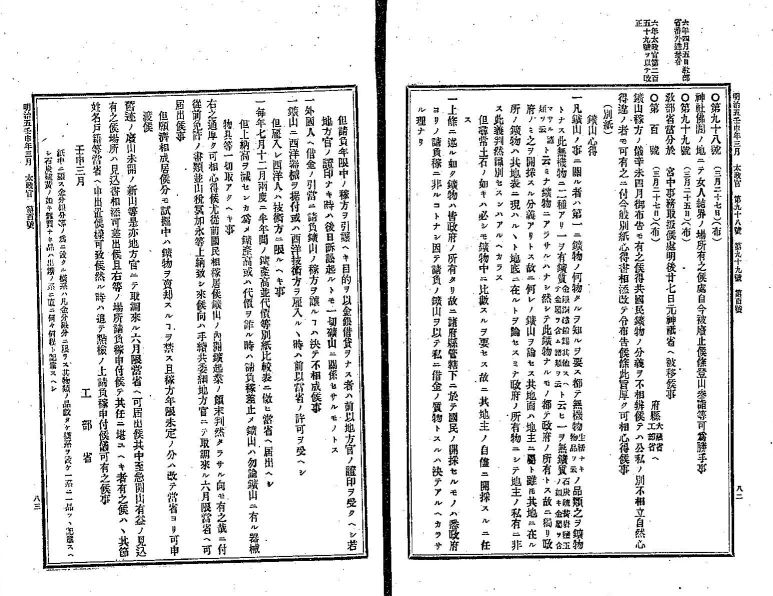

Dajokan (the Grand Council of State) Proclamation No. 98, March 1872

"Temples and shrines must abolish bans on women and allow mountain climbing."

2) E. P. Hughes (Translated by OGATA Ryusui), Tozan no Setsu (登山の説, lit. About climbing mountains) in Eikoku no Fuzoku (英国の風俗, lit. English Life), Chishin-kan, 1902 [96-138]

This is a translation of a lecture given by Elizabeth Philip Hughes (1851-1925), a British female educator, at the general meeting of the Great Japan Women Hygiene Association when she visited Japan to observe the education situation. It was serialized in three issues of Kokumin Shimbun (国民新聞) [YB-188] starting from March 11, 1902.

Hughes had enjoyed climbing mountains since she was in Europe, and she once climbed the Alps with her Japanese friends. Even after she came to Japan, she climbed Mt. Fuji, Mt. Asama, and other mountains. In this lecture, she said, "I hope you will try climbing mountains more" because Japan is full of wonderful nature. Explaining the benefits of mountaineering, she recommended it especially for women who do not do much physical work. It is true that climbing mountains puts a burden on the body, but it is good for your health.

Also, "oil" is listed as equipment for mountain climbing. It says, "As you climb the mountain, the sun gets closer, and you get sunburned, so please spread that oil on your face," and you can see the worries of women that have not changed since a long time ago.

Mountaineering for research

In the Meiji period, many people started to climb mountains for research and investigation. People who learned modern science through studying abroad and the guidance of foreign government advisers such as Gowland conducted surveys and research on topography, weather, geology, mining, and botany.

Surveying

The Military Land Survey (forerunner of the Geospatial Information Authority of Japan), which was responsible for creating the national land map, dispatched personnel to mountains throughout Japan for survey work(Japanese Official Gazette (官報) No.1459 [YC-1]). This is because triangulation points used for surveying needed to be seen from a distance and were often set up in high places such as near the top of a mountain. The Sankaku Sokuryo Hoshiki (三角測量法式, lit. Triangulation) [特25-127], which defined the method of measurement at the time, says "the selection point should be as flat a mountain or as high a volcanic mountain as possible" and explains the need to climb mountains.

Perhaps the most well-known mountain climbing by land surveyors is the surveyor SHIBAZAKI Yoshitaro's ascent of Mt. Tsurugidake. The Sankaku Sokuryo Hoshiki mentioned above lists "towering rock formations" as an obstacle to mountain climbing, and Mt. Tsurugidake is a typical example of this, a steep mountain that is not easy to climb. The journey is well known because it was portrayed in the novel Tsurugidake Ten no Ki (剣岳 点の記) [KH718-J141] by NITTA Jiro. In order to climb Mt. Tsurugidake, not only the efforts of SHIBAZAKI and other land surveyors were indispensable, as was the cooperation of UJI Chojiro and others, who acted as mountain guides.

This kind of help from local mountain guides can be seen in other mountains. YAMAMURA Motoki's Hajime no Nihon Alps (はじめの日本アルプス) [GK11-J28] includes a drawing by TATE Kiyohiko, a member of the land survey team, climbing Mt. Hotaka in the Hida Mountains to select triangulation points. It depicts TATE in Western clothes, dressed in a suit with an umbrella, and KAMIJO Kamonji, a mountain guide, in traditional attire. The great task of surveying the whole of Japan required the patience of mountain surveyors as well as wisdom and traditions that had been cultivated locally.

The National Diet Library has many maps made by the Military Land Survey.

Meteorological observation

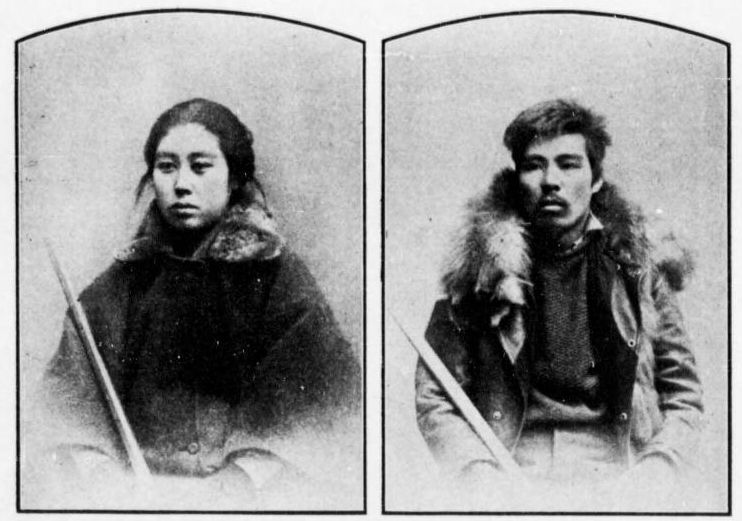

In Japan, weather forecasts started in 1884, but at that time, observation data was insufficient and not very reliable. In 1895, a meteorologist, NONAKA Itaru, built a simple observation hut on the top of Mt. Fuji at his own expense to make winter weather observations and demonstrate the possibility of high-altitude weather observations. After 82 days of struggle, NONAKA's attempt to pass the winter at the summit was thwarted by cold weather and strong winds. This story was later compiled as Fuji Annai (富士案内, lit. Guide to Mt.Fuji).

3) NONAKA Itaru, Fuji Annai (富士案内), Shunyodo, 1901 [88-192], Corrected reprint edition, Shunyodo, 1907 [88-192イ]

Part of this book is a guidebook for climbers. However, it has dramatic content with detailed descriptions of the significance of the high-altitude weather observation at the top of Mt. Fuji, the history of the construction of the observatory, actual records of observation, various obstacles due to the harsh environment, and symptoms of altitude sickness and malnutrition. NONAKA tried to climb Mt. Fuji twice in the midwinter before performing observations, which itself can be said to be a great achievement in the history of mountain climbing because until then no one had climbed Mt. Fuji in the middle of winter. The first time, NONAKA turned back at the fifth station, and the second time, they succeeded in reaching the summit thanks to newly prepared pickaxes and shoes with cleats they made themselves. At the end of the book, there is a passage saying, "I recommend mountain climbing in the winter." This challenge was a very much ahead of its time as both a mountaineering record and as meteorological observation.

NONAKA’s weather observation was originally planned to be carried out by a single person. However, soon after it started, his wife, Chiyoko, came to visit out of concern for her husband and unexpectedly it became a joint effort by the couple. Although the plan itself failed, it became a popular topic as a great achievement. It was featured in many literary and visual works. It was in 1932, 37 years later, that a meteorological station was established on the top of Mt. Fuji, and year-round observation was achieved.

Column: MATSUURA Takeshiro, the pioneer of mountain climbing

When Japan opened the country to the rest of the world, there was already a person who had climbed various mountains and left many travel writings. That person was MATSUURA Takeshiro. He was known for exploring the inland areas of Ezo at the end of the Edo period and making the original suggestion for the name "Hokkaido."

MATSUURA was born in Sugawa, Ichishi in Ise Province (present-day Onoe-Cho, Matsusaka City, Mie Prefecture) in 1818. His records contain 66 climbing trips in total, from his first climb of Mt. Togakushi in Shinshu at the age of 16, to climbing Mt. Fuji at the age of 70. When he was 16 years old, he ran away from home to travel to the shogunate capital, Edo, and climbed Mt. Togakushi on his way home. In his autography, he said, "The landscape of Kiso and the scenery of Tokaido drove me to wander," which indicates his strong passion for traveling.

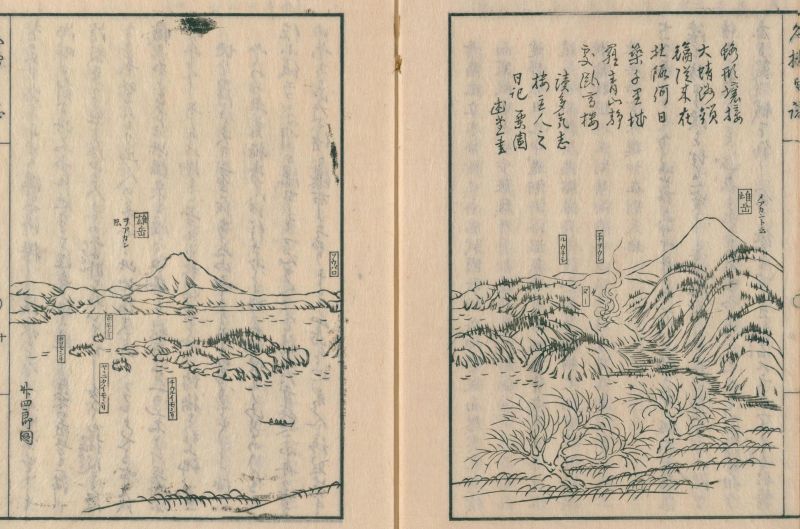

In 1845, at the age of 28, he went to Ezo, and since then, he traveled to Ezo six times in 14 years. MATSUURA, who felt sad about the harshness of the Ainu policy adopted by the Japanese, wrote detailed records of the situation in the area and published various books including Kinsei Ezo Jinbutsushi (近世蝦夷人物誌, lit. Account of the people of Ezo in recent times) (Nihon Shomin Seikatsu Shiryo Shusei (日本庶民生活史料集成, lit. Collection of Historical Materials on the Life of Common Japanese people), Volume 4 [382.1-N6882]).

In 1858, he surveyed Kushiro, Abashiri, Shari, Mashu, Nishibetsu, Teshikaga, and Lake Akan to investigate the geography of eastern Hokkaido, before returning to Kushiro again. He compiled these travels in Kusuri Nisshi (久摺日誌, lit. Kusuri Diaries) [特1-73] ("Kusuri" means Kushiro). During the trip, he took eight Ainu people who were strong walkers and climbed several steep mountains. When climbing Mt. Kamui, it seemed difficult to climb past the eighth station due to rock slides and falls. He asked his Ainu companions if they really could go further, and one of the Ainu said, "No one has ever climbed to the top of this mountain. And yet, because you were going up first, we had no choice but to follow you." MATSUURA himself thought that he could climb because the Ainu followed without trying to stop him. He laughed at this unexpected answer. When he gave up and tried to descend the mountain, one of the Ainu took the lead and began to climb the mountain again. The group followed him tenaciously and finally reached the top of the mountain.

Teigai Zenki (丁亥前記) [GB391-75] has the description of MATSUURA meeting Gowland on May 2, 1887, and we can guess they had a lively discussion about mountains.

Next Chapter 2:

Two major climbers

in the spread of mountain climbing