- Kaleidoscope of Books

- Dawn of Mountaineering - Mountains and People in Modern Japan

- Chapter 3: Establishment of the Japanese Alpine Club and promotion of mountain climbing

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: New-style mountain climbing

- Chapter 2: Two major climbers in the spread of mountain climbing

- Chapter 3: Establishment of the Japanese Alpine Club and promotion of mountain climbing

- Appendix: Mountains and Food

- References

Chapter 3: Establishment of the Japanese Alpine Club and promotion of mountain climbing

In the latter part of the Meiji period, people started climbing mountains under the influence of SHIGA Shigetaka and Walter Weston, who were introduced in Chapter 2. They wanted to enjoy mountain climbing purely for the sake of it, not for religion, making a living, research, or other reasons. The number of people who like mountaineering gradually grew, and the Japanese public's perception of mountains changed, so eventually climbing mountains became not such a special event. In this chapter, we will look at the circumstances surrounding the establishment of the Japanese Alpine Club, where climbers gathered. Also, we will introduce literature and paintings depicting mountains, mention instructions on mountain climbing in school education, and trace the spread of climbing mountains for pleasure.

Establishment of the Japanese Alpine Club

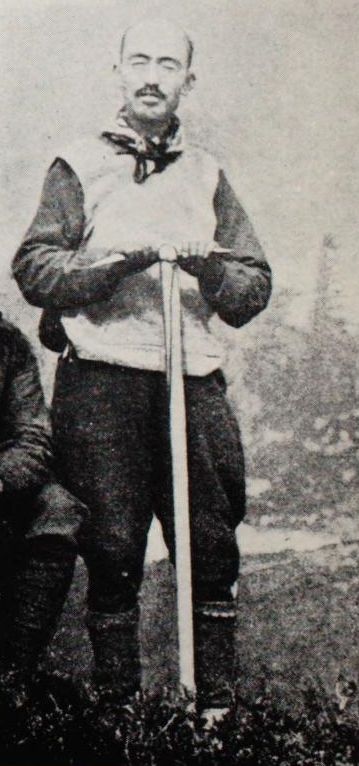

Japan's first mountaineering group (in the early days, it was just called the "Alpine Club"), the Japanese Alpine Club, was established in 1905 by KOJIMA Usui and others. While working at Yokohama Specie Bank, he enjoyed mountain climbing in his spare time and left many travel essays and reviews. He was also known as a collector of ukiyo-e (Japanese woodblock prints) and other works of art.

7) KOJIMA Usui, Alpinist no Shuki (アルピニストの手記, lit. Alpinist's Memoirs), Shomotsu Tenbosha, 1936 [712-60]

This is a journal left by Usui in his later years. It is one of his most well-known works and is considered a masterpiece among Japanese mountain books. He was well versed in art, so he was particular about the binding of his own book. The limited edition, which was sold only in limited quantities, has beautiful lacquer work on it and is highly prized by book lovers. The contents consist of the background behind the establishment of the Alpine Club, critical biographies of various people like SHIGA and Weston who Usui knew, memories of books about mountains, and his personal history. It is an indispensable primary material to trace the history of mountain climbing in the Meiji period.

In 1902, inspired by Nihon Fukei Ron [45-67], he tried climbing Mt. Yarigatake with his friend. They finally reached the top of an unknown steep path with difficulty. He felt a great sense of accomplishment, as he became a pioneer of mountain climbing. The following year, however, he stumbled upon Weston's book, Mountaineering and exploration in the Japanese Alps, which was introduced in Chapter 2. He learned of the existence of Westerners who had climbed Mt. Yarigatake before him. He even found out unexpectedly that Weston was staying in Yokohama in the meantime. He visited Weston with his friend and learned that there were alpine clubs for mountain climbers in other countries all over the world. Two years later, Weston invited Usui to his hotel a few days before his return to England. At the hotel, he enthusiastically encouraged Usui to establish an alpine club. At a later date, Weston assisted him in receiving a letter from the Alpine Club of England encouraging him to establish an alpine club. Encouraged by this support, Usui felt as if "the lightning ripped the paper he was touching and ran through his body." It drove him to work energetically to establish the Alpine Club.

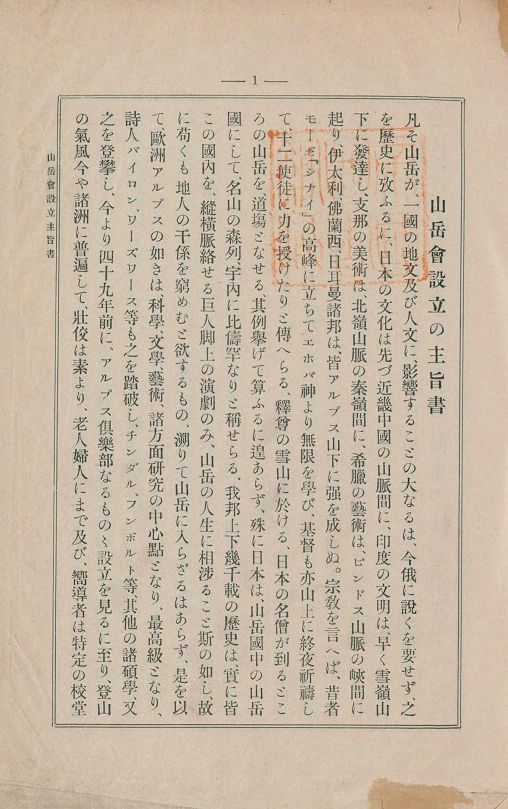

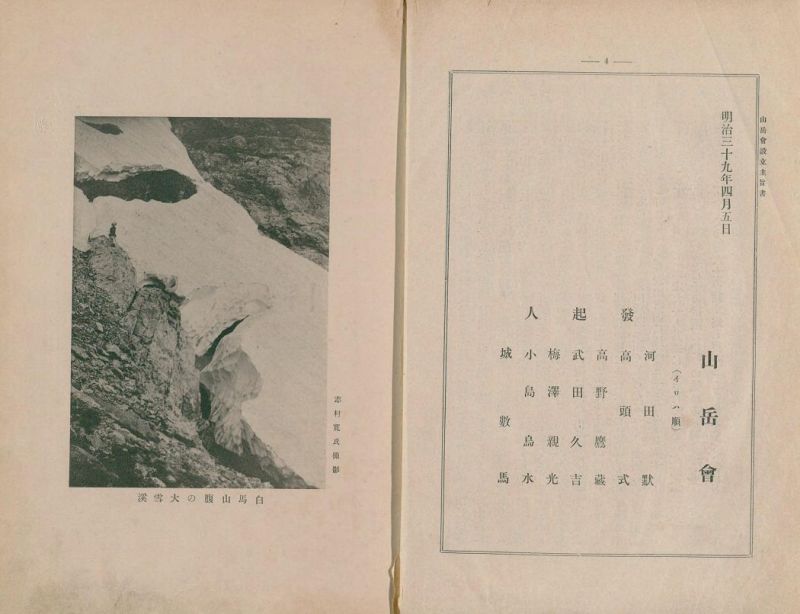

8) “Sangakukai Setsuritsu no Shushisho”(山岳会設立の主旨書, lit. Statement of intent for the establishment of Alpine Club), Sangaku (山岳), Year 1, Issue 1, 1906 [Z11-375]

This declaration was published in the first issue of Sangaku, the journal of the Japanese Alpine Club. Reprints were also distributed to newspaper and publishing companies in order to attract members. In the same way as Nihon Fukei Ron, this declaration explained the beauty of mountains and their close connection to the land and culture. In addition, it clarified the significance of mountain climbing and called for solidarity among climbers. The beautiful writing style is similar to that of Nihon Fukei Ron, but this is also a characteristic of the early writings of Usui. It is a text that symbolizes the Japanese Alpine Club, and was also included at the beginning of Nihon Sangaku-kai Hyakunen-shi (日本山岳会百年史, lit. 100 Years of Japanese Alpine Club History) [FS4-H107], published in 2007, along with a revised modern version.

Many young people, including TAKEDA Hisayoshi, cooperated in establishing the Alpine Club. The second son of Ernest Satow, TAKEDA later became a botanist and was called the "father of Oze." The purpose of their climbs was to collect plants and insects, and many natural history articles appeared in the early issues of Sangaku.

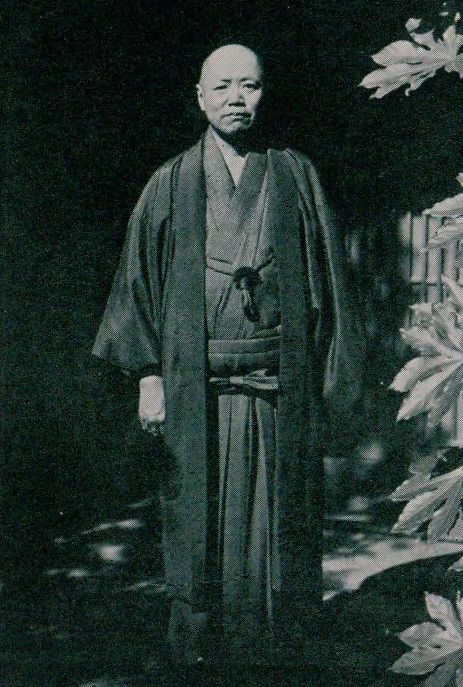

Also, TAKATO Shoku supported the early Alpine Club financially. TAKATO was a large landowner in Niigata Prefecture, and he paid the membership fees for 1,000 people for 18 years after the establishment of the Alpine Club. There is a theory that the reason why the number of people from Niigata Prefecture stood out among the members in the early days of the Alpine Club is that TAKATO paid the membership fees and had local acquaintances join the club. TAKATO was inspired by Nihon Fukei Ron, and with the help of SHIGA and Usui, he published Nihon Sangaku-shi (日本山岳志, lit. The mountains of Japan) at his own expense.

9) Nihon Sangaku-shi, edited by TAKATO Shoku, Hakubunkan, 1906 [23-254]

This is the first encyclopedia of mountains in Japan, and it is very substantial, covering 2,130 mountains in 1,360 pages. According to TAKATO, before the publication, prospects seemed bleak, saying "When I was about to publish Sangaku-shi in March of last year, some people advised me to reduce the number of copies because it was far from a good seller." Upon its release, he was surprised by the unexpected response. He said, "However, there were more than a dozen special volunteers who pointed out the fallacies in Sangaku-shi. I did not expect that there were so many people who like mountains." The sales of this book predicted the future of the Alpine Club. It was published before the publication of Sangaku (journal), and Nihon Sangaku-shi readers got a supplement of a reprint of the “Statement of intent for the establishment of the Alpine Club.” Conversely, the supplement of this book was attached to Sangaku (journal) as an appendix. As this is a special book for the Japanese Alpine Club, as part of the 100th anniversary of the founding of the Association in 2005, a new version of the book, Shin Nihon Sangaku-shi (新日本山岳誌, lit. New Version of the Mountains of Japan) [GB645-H332], was published.

The Alpine Club developed steadily, and Weston and SHIGA were nominated as honorary members. Early members included literary men such as SHIMAZAKI Toson, TAYAMA Katai, SHIMAGI Akahiko, YANAGITA Kunio, OSANAI Kaoru, and IRAKO Seihaku, and painters such as TAKASHIMA Hokkai, OSHITA Tojiro, MARUYAMA Banka, and IBARAGI Inokichi. This is due to Usui's connections, but it also shows their affinity for literature and art. Unique mountaineering groups were established in various places, and the momentum of mountain climbing grew.

Mountain climbing depicted in literature and art

Even in the Meiji period, many men of culture liked mountains. There were many unique people, such as great writers whose works are suggestive of the Edo period, poets who climbed mountains as seriously as professional mountain climbers, and mountain painters who loved mountains so much they disappeared in them. Here, we introduce people of culture who were fascinated by mountains, and their works.

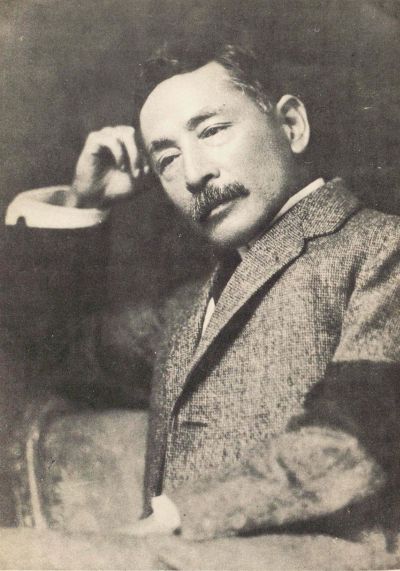

NATSUME Soseki (1867-1916)

"As I climbed the mountain path I ponder..." This is the beginning of NATSUME Soseki's Kusamakura (草枕, lit. Grass Pillow), which is well known in Japan. It is believed that Soseki first climbed Mt. Fuji in 1887, when he was only 20 years old. It was the year before Weston came to Japan. Four years later, he climbed Mt. Fuji for the second time, and the following year he also climbed Mt. Hiei and Mt. Myogi. He often climbed mountains when he was a teacher at the Fifth High School in Kumamoto. In particular, his experience of climbing Mt. Aso with his friend in 1899 and getting lost due to bad weather led to the creation of Nihyaku Toka (二百十日, lit. The 210th day).

10) NATSUME Soseki, Nihyaku Toka (二百十日), included in Uzurakago (鶉籠), Shunyodo, 1907 [26-375]

This piece first appeared in Chuokoron (中央公論) [Z23-9] in October 1906, and was published immediately after that in the novel collection Uzurakago (鶉籠, lit. Quail Cage). This collection also included Botchan (坊ちゃん) and Kusamakura, and became a best seller. Nihyaku Toka (二百十日) means the 210th day from Risshun (the first day of spring), which falls around September 1. According to the traditional Japanese calendar, typhoons tend to come this time of year, and it was on this day that Soseki was caught in a storm in Aso. The characters are young people called Kei and Roku, and the story is about two people climbing Mt. Aso to the crater while having a light conversation similar to rakugo (traditional comic storytelling). It has a happy-go-lucky and optimistic atmosphere, but here and there, you can see Soseki's unique theme of the nature of modernization.

Other Meiji literary masters who enjoyed climbing are KODA Rohan, TAYAMA Katai, and TOKUTOMI Roka. TOKUTOMI wrote a record of mountain climbing in Aso from a different point of view from Soseki in Natsu no Yama (夏の山, lit. Summer Mountain) (Seizan Hakuun (青山白雲, lit. Blue Sky and White Clouds)) [679-51]). TERADA Torahiko also wrote a letter to his mentor Soseki while he was visiting Europe in 1910. According to the letter, he was asked suddenly "Aren't you Japanese?" on a mountain path on the way back from a visit to a glacier in the Alps, and the person who asked was Weston(![]() Sensei eno Tsuushin (先生への通信, lit. Letters to the Mentor), Aozora Bunko).

Sensei eno Tsuushin (先生への通信, lit. Letters to the Mentor), Aozora Bunko).

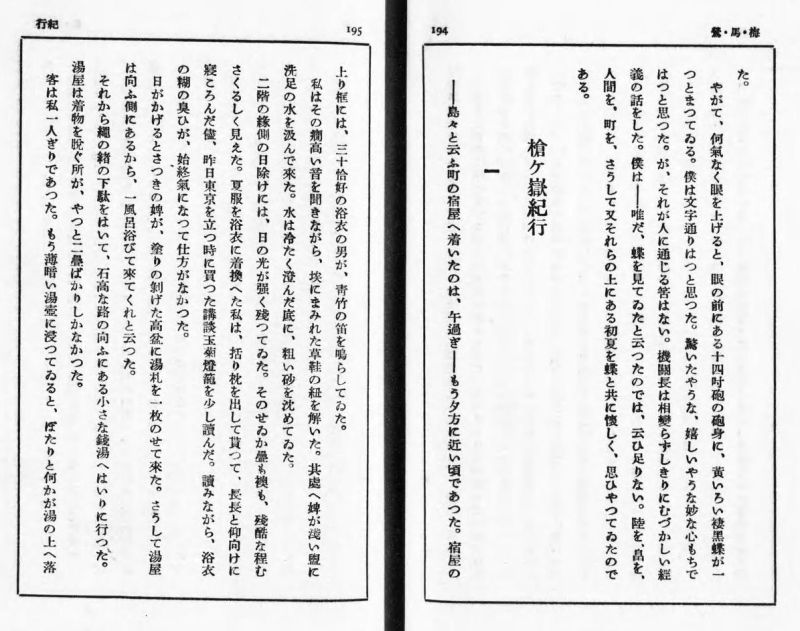

AKUTAGAWA Ryunosuke (1892-1927)

AKUTAGAWA Ryunosuke wrote a well-known travel journal titled Yarigatake Kiko (槍ヶ嶽紀行, lit. The Travel to Mt.Yarigatake). You can see this sentence: "This was the famous Kamonji hut where the climbers of Mt. Yarigatake often lodged since the time of KOJIMA Usui."(Ume, Uma, Uguisu (梅・馬・鶯, lit. Plum, Horse, Nightingale) [536-240]). It is believed that AKUTAGAWA actually climbed Mt. Yarigatake in 1909 when he was 17 years old, four years after Usui and others established the Japanese Alpine Club. Moreover, the experience of these young days is reflected in the portrayal of Kamikochi in his later novel Kappa (河童, lit. Water imp) [貴7-98]. In addition to Mt. Yarigatake, he is known to have climbed Mt. Akagi, Mt. Haruna, and Mt. Ontake. You can get a glimpse of an unexpected side of AKUTAGAWA, who has an image of being delicate.

TAKAMURA Kotaro (1883-1956), KUBOTA Utsubo (1877-1967)

Sculptor TAKAMURA Kotaro wrote in a passage of Chieko Sho (智恵子抄, Chieko’s sky) that he stayed with the Westons at a hot spring inn in Kamikochi. In 1913, TAKAMURA traveled with Chieko before their marriage, and it was reported in the newspaper as “sanjo no koi (山上の恋, lit. Love on the mountain).” When Weston questioned him about his relationship with her, he answered, “My friend.” (Chieko Sho [911.56-Ta45aウ]). KUBOTA Utsubo, a poet, and IBARAGI Inokichi, a painter who will be described later, were also staying at the same hotel. When they were talking and laughing loudly, Weston, in the next room, warned them to be quiet (Utsubo, Nihon Alps e (日本アルプスへ, lit. To the Japanese Alps) [360-441]). Born in Nagano Prefecture, Utsubo was familiar with mountains since childhood and left many mountain poems. The anthology Chosei Shu (鳥声集, lit. Collection of Bird Sounds) [特106-524] includes an impressive poem: “Yarigatake: Clinging to the rock at the top of the mountain, I stood in the middle of the sky.”

OMACHI Keigetsu (1869-1925)

OMACHI Keigetsu, known as a poet and essayist, learned of Weston in a manuscript he received from Usui in 1905 when he was editing magazines at Hakubunkan Company. In his reply to Usui, he wrote about his desire to climb Mt. Yarigatake, Mt. Akaishidake, and Mt. Shiramine (Mt. Kitadake) as Weston did.

11) OMACHI Keigetsu, Kanto no Sansui (関東の山水, lit. Mountains and Waters in the Kanto Area), Hakubunkan, 1909 [17-449]

The first travelogue of landscapes compiled as Nihon Sansui Kiko (日本山水紀行, lit. Travelogue of Japanese Mountains and Waters) after the death of Keigetsu. It introduces the mountains throughout the Kanto area which were familiar to Keigetsu, such as Mt. Tsukuba, Mt. Koshin, Mt. Buko, Mt. Akagi, Mt. Ontake, and Mt. Takao. In the past, people climbed only a limited number of mountains. However, he was very enthusiastic about climbing all the famous mountains in Japan, saying, "I want to explore all over Japan." In addition, he said, "I won't give up going wherever people can go. If there is a landscape to look at, I will definitely find it." The preface also tells us that Keigetsu was making use of the 1:20,000 and 1:50,000 topographical maps of the Japanese Imperial Land Survey, and documents such as Nihon Fukei Ron and Nihon Sangaku-shi. Also, descriptions of trains and steamships can be seen here and there, and you can feel the existence of railways and sea transportation that were rapidly developing at that time.

Keigetsu traveled around the country and wrote more than 500 essays about his travels. He became one of the main characters in the "sansui (mountains and waters) boom," which began in the late Meiji and Taisho periods. In addition to Keigetsu, many other writers wrote a variety of travel essays on the theme of "mountains and waters," stimulating the reader's passion for travel.

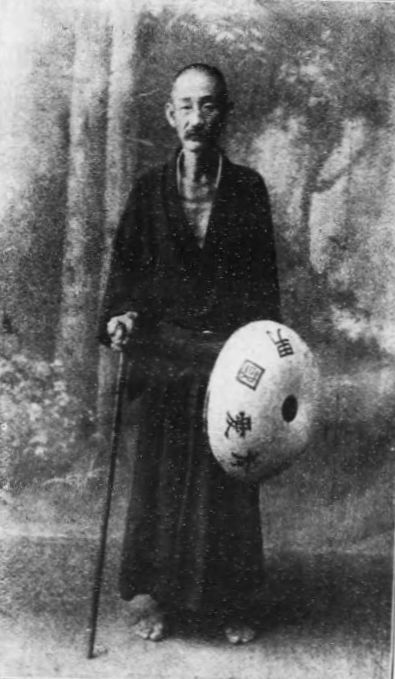

KAWAHIGASHI Hekigoto (1873-1937)

Like Keigetsu, the haiku poet KAWAHIGASHI Hekigoto also had a strong attachment to mountain climbing. He described his traverse from Harinoki Pass to Tateyama, Mt. Yarigatake and Kamikochi in 1915 in Nihon Alps Judanki (日本アルプス縦断記, lit. The Japanese Alps Traverse Records) [363-222] (co-authorship). In Nihon no Sansui (日本の山水, lit. Mountains and Waters in Japan) [356-105], written in the same year, while acknowledging the achievements of Weston, SHIGA, and Usui, he expressed his ambition to create new theories of landscape in its preface.

OSHITA Tojiro (1870-1911)

OSHITA Tojiro, who spread watercolor painting in Japan with his technique book Suisaiga no Shiori (水彩画之栞, lit. A Guide to Watercolor Painting) [29-258], repeatedly made sketching trips to the mountains of Mt. Hotaka, Mt. Kitadake and Mt. Komagatake. He deepened his friendship with SHIGA and Usui, joined the Japanese Alpine Club, and made cover paintings and contributions for Sangaku [Z11-375]. In 1905, he launched the art magazine Mizue (みづゑ, lit. Watercolor Painting) [Z11-181] and tried to popularize watercolor painting. However, he died young at the age of 41. Afterward, Usui together with MORI Ogai and others, helped to keep the magazine alive. Ogai was on close terms with OSHITA and wrote the preface to Suisaiga no Shiori. After OSHITA’s death, Ogai wrote the novel Nagashi (included in Somatoh (走馬灯, lit. A Revolving Lantern) [338-188]) in which he appeared as the main character.

YOSHIDA Hiroshi (1876-1950)

YOSHIDA Hiroshi, who was known as a world-famous landscape painter in the Meiji, Taisho, and Showa periods, also made many mountain paintings and woodblock prints. He loved mountains so much that he named his second son Hodaka. His book Kozan no Bi wo Kataru (高山の美を語る, lit. Talking about the beauty of high mountains) [595-341] discussed the beauty of the mountains from the perspective of a painter. However, it is unique in that it has the aspect of personal mountain climbing records and mountain climbing instruction. In 1936, he established Nihon Sangakuga Kyokai (日本山岳画協会, Association des Artistes Alpins) together with IBARAGI and others.

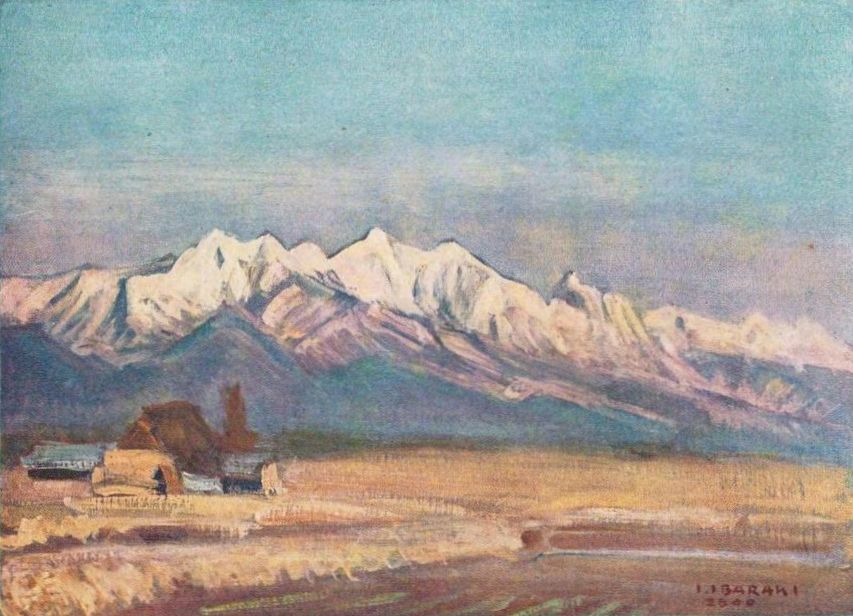

IBARAGI Inokichi (1888 -1944)

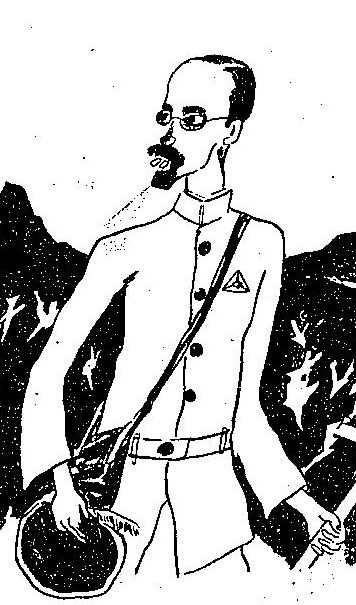

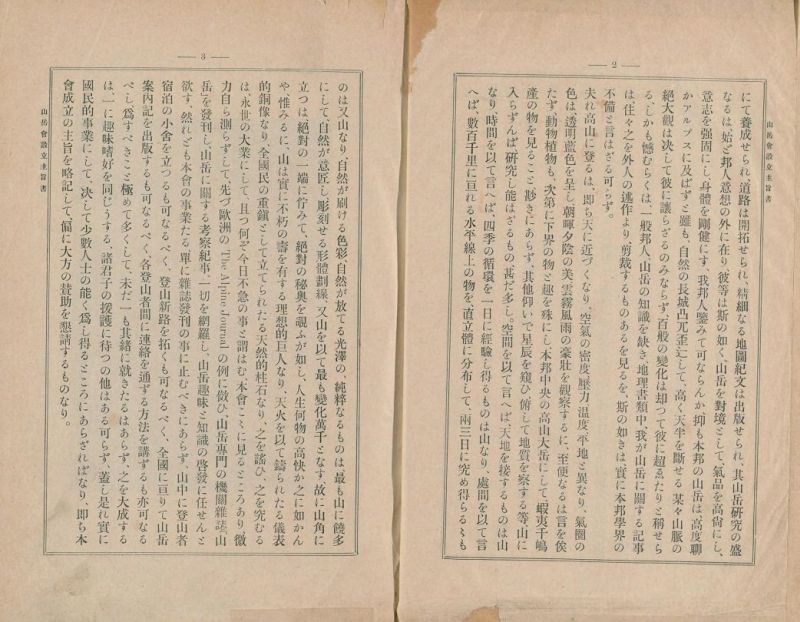

It might be IBARAGI Inokichi who was loved the most by early mountain climbers as a painter. He lived near Usui and was invited to start mountain climbing in earnest. The picture at the beginning of Alpinist no Shuki [712-60] was painted by him, and he often painted the cover of Sangaku [Z11-375]. There is also an anecdote that he secretly removed the relief of the Weston Monument in Kamikochi and brought it back to the Japanese Alpine Club during the war to protect it from being contributed as metal during WW II. He went missing on Mt. Hotaka and was never heard from again.

IBARAGI Inokichi, "In the morning, you can see Mt. Jiigatake, Mt. Kashima-Yarigatake and Mt. Goryu, which make up the Ushirotateyama mountain range. The view to the northwest from the Jonen trail, entering Karasugawa Village from Toyoshina, Minami Azumi district, Shinshu."

Climbing in schools

SHIGA wrote, “School teachers must strive to greatly cultivate the spirit of mountaineering among students" in his book Nihon Fukei Ron [45-67] in 1894. Mountain climbing was introduced into the curriculum in many schools in the 1900s. In Gakko Taiso Kyoju Yomoku (学校体操教授要目, lit. Syllabus of School Physical Education) [特113-486] established by the Ministry of Education in 1913, "excursions and mountain climbing" were included as a variety of exercises to be carried out outside of physical education teaching hours. The Ministry of Education’s Taisho 7, 8, 9 3kanen ni okeru Zenkoku Kaki Taiikuteki Shisetsu (大正七、八、九、三箇年間に於ける全国夏季体育的施設, lit. National Survey of Facilities for Summer Physical Exercises for Three Years, 1918, 1919, and 1920) [276-302] shows examples of summer physical education activities by several schools. Here are some examples of Nagano Prefecture, which is famous as an educational prefecture and is blessed with high mountains.

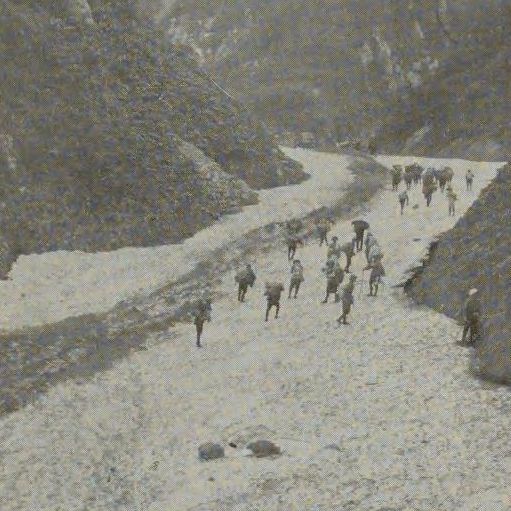

From 1902 to 1925, all fourth graders at Nagano Prefectural Nagano Girl's High School (now Nagano Prefectural Nagano Nishi High School) conducted annual group mountaineering trips to Mt. Togakushi and other mountains. Mt. Togakushi has a famous rough spot called "Ari no Towatari (proceeding like ants over a steep cliff)." We can picture the scene of female students in those days encouraging each other and calling up all their courage to get through the difficulty. This group climbing was started by WATANABE Hayashi, the first principal of the school. He is known as a pioneering educator. For example, he conducted unique open scientific experiments using flasks ( Kin’i Butsuri Ichibin Hyakken (近易物理一壜百験, lit. Easy Physics Experiments with Flasks) [特24-450]). On the other hand, he also left a mark in the world of mountain climbing, having climbed Mt. Hakuba as early as 1883. (Kyoiku Korousha Retsuden (教育功労者列伝, lit. The lives of distinguished educators) [255.1-127])

SHIMAGI Akahiko, a poet, wrote a travelogue called Joshi Kirigamine Tozanki (女子霧ケ峰登山記, lit, The Girl’s Mt. Kirigamine Mountaineering Record) under the name of KUBOTA Kakimuraya (久保田柿村舎) for the first issue of Sangaku [Z11-375]. At that time, he was a teacher in Nagano and led female students to climb Mt. Yatsugatake and Mt. Kirigamine. The preface, which begins with "I strongly support female climbing," states that "around 1902, groups of girls' schools in various regions began to try to climb Mt. Fuji." This description indicates the growing momentum for women to climb mountains. It was around this time that a female student, HIRATSUKA Raicho, who became a well-known activist for the women's liberation movement in the future, became obsessed with climbing Mt. Fuji.

While school mountaineering became more popular, some tragic accidents occurred. The disaster on Mt. Kisokomagatake on August 26, 1913, was the subject of Seishoku no Ishibumi (聖職の碑, lit. The Clerical Monument) [KH437-85] by NITTA Jiro.

SHIMAGI Akahiko, Joshi Kirigamine Tozanki (女子霧ヶ峰登山記)

SHIMAGI Akahiko, Joshi Kirigamine Tozanki (女子霧ヶ峰登山記)

12) Kamiina gun Kyoiku kai (上伊那郡教育会, lit. Kamiina district educational society), Shinshu Komagatake Sonan Shimatsu (信州駒ケ嶽遭難始末, lit. Shinshu Mt. Komagatake Incident) (Sangaku, Year 8, Issue 3, 1913 [Z11-375] p.518-538)

This is a report of an accident that killed 11 people, including teachers and students of Nakaminowa Senior Elementary School (present-day Minowa Town Minowa Chubu Elementary School, and Minowa Junior High School), in Nagano Prefecture. You can also see the details of the school climbing plan at that time, such as the purpose, schedule, itinerary, clothes, food, personal effects, and precautions. The cause of the accident was the damage to the mountain hut where they were planning to stay and the worsening weather. At first, the school was severely criticized for its inadequacies. However, because the school had made careful preparations for the mountain climbing every year, it seems that the philosophy of school mountain climbing itself was not denied. People said, "This should not diminish the spirit of mountaineering." (Nagano Shimbun (長野新聞, lit. Nagano Newspaper) September 2, 1913).

The next year, a disaster memorial monument was built. After that, mountain trails and stone chambers for evacuation were set up. At the school, climbing Mt. Komagatake was resumed in 1925, the 13th anniversary of the victim's death. The event has been carried on through to the present day.

Some students were not satisfied with mountain climbing as school events and tried to climb mountains of their own volition. At the Second Higher School (later, the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, Tohoku University), students who admired mountains formed an alpine club in 1914, and climbed Mt. Zao and the Japanese Alps. They hosted lectures by inviting organizers of the Japanese Alpine Club (Shoshi kai Zenshi (尚志会全史, lit. All History of Shoshikai) [283-69] edited by the Second Higher School Shoshikai). Many of these students joined the Japanese Alpine Club after graduation and continued climbing. It is easy to imagine that the spread of school climbing greatly expanded the base of mountain enthusiasts.

Conclusion

In 1915, ten years after the founding of the Japanese Alpine Club, Weston, already a celebrity among mountaineers, returned home after his third (and final) visit to Japan. It was also in this year that Usui left the center of activities of the Japanese Alpine Club due to his 11 and a half years of overseas assignment. However, starting with the alpine club of Keio University, other university alpine clubs were established one after another in the same year. University students became new leaders in spreading mountain climbing. The later generation of mountaineers enjoyed mountaineering in a variety of ways, from pushing the limits of their skills and physical strength by challenging the high peaks, such as the Alps and the Himalayas, to seeking spiritual fulfillment by quietly going deep into the mountains.

In recent years, mountains have become more familiar due to the growing popularity of leisure activities, the development of infrastructure such as ropeways and mountain huts, and the spread of inexpensive, high-quality mountaineering equipment. While anyone regardless of age and gender can enjoy mountain climbing with ease now, various media are calling for risk awareness and the need to improve good manners. We would be happy if, while listening to such topics about mountains, you could think about the people of the Meiji era who started our familiarization with mountains.

Next

Appendix: Mountains and Food