- Kaleidoscope of Books

- The Rimpa School and Its Influence as Seen in Books

- The Rimpa school crosses the sea

The Rimpa school crosses the sea

The Rimpa school is an aspect of Japanese culture that had a strong effect on artists in Europe, particularly those involved in Japonisme, which in turn was an antecedent of Art Nouveau.

Art Nouveau was an art movement characterized by botanical patterns and flowing curves that was popular in Europe from the end of the 19th century to the beginning of the 20th century, mainly in France. Japonisme is an interest in Japanese art which was seen in Europe in the 19th century as represented by international expositions displaying Japanese art and design. With Japanese culture being held in such high regard throughout Europe, the Rimpa school was soon reevaluated in Japan, as well.

In this chapter, "The Rimpa school crosses the sea," we introduce some of the individuals who discovered the Rimpa school during the late Edo and Meiji periods.

Spreading overseas

Philipp Franz von Siebold

Although Japan had closed itself off to most of the world during the late Edo period, it did maintain a trade relationship with the Netherlands through the small, artificial island of Dejima in Nagasaki. Thus, the Netherlands played a major role as an overseas window to Japanese culture.

A doctor dispatched to Japan by the Netherlands, Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold (1796-1866), conducted a scientific survey of Japan and wrote Japan as the culmination of his research. He brought back from Japan a collection of materials, including multiple volumes of Korin Hyakuzu, part of which is still held by the Museum Volkenkunde (Netherlands, Laiden). (TANABE Yoshitaro, Siebold collection (bunken) no genjo – Oranda, igirisu, furansu - (lit. Current Situation of the Siebold Collection (Literature): Netherlands, England, France-), Sanko Shoshi Kenkyu (Reference Service and Bibliography) No. 22, 1981.6. [Z21-291])

There are also records of selling some of the Japanese literature from the collection to England and France. The Korin Hyakuzu which is possessed by the Bibliothèque nationale de France is one of these collections.

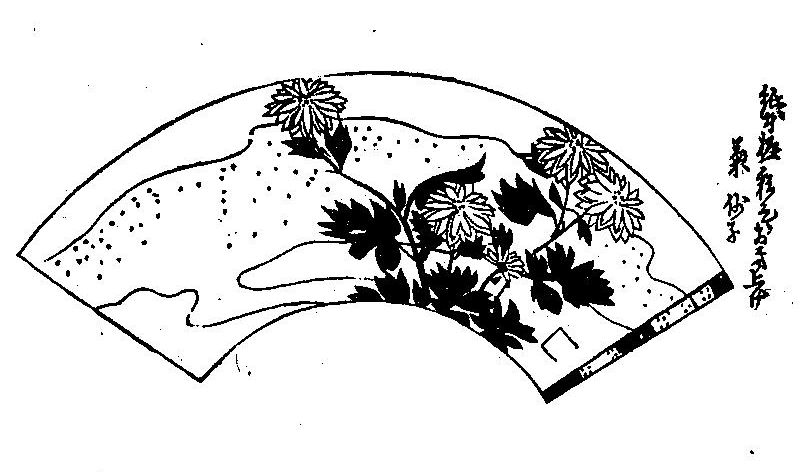

9) Korin Hyakuzu first part, OGATA Korin (paint), SAKAI Hoitsu (ed.) , Hakubunkan, 1894 [特67-136]

A collection of Korin's designs published by Sakai Hoitsu at the time of the 100th anniversary of OGATA Korin's death in 1815. Korin gained acclaim in Europe while Japonisme was in vogue, and artists there took ideas from his fan designs.

Ernest Fenollosa

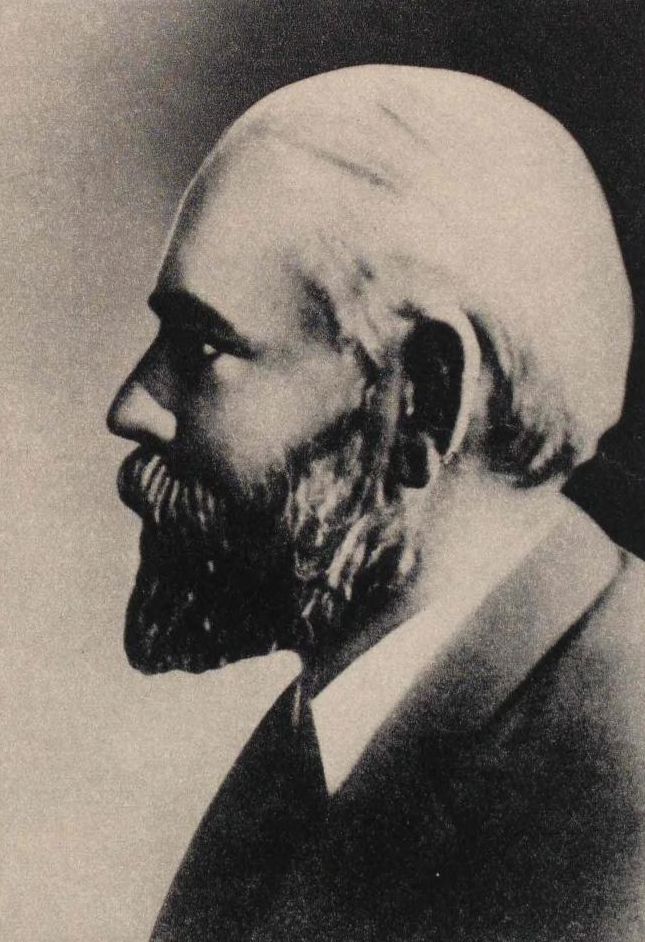

Ernest Francisco Fenollosa was one of a number of foreign engineers and professors who were invited to Japan by the Meiji government. At that time, they were projecting a rapid modernization by absorbing Western cultures.

He was very interested in oriental art since he lived in Boston, USA. He not only taught politics, economics, and philosophy at university, but also researched Japanese painting and wrote a general treatise on oriental art, entitled Epochs of Chinese and Japanese Art or Toa Bijutsushi ko. Regarding Rimpa, he highly appreciated the juxtaposition of craft and art, that the Japanese people were not aware of.

He collected Japanese paintings, and later sold these collections on the condition that they were deposited at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston. This museum holds part of his collections as the "Fenollosa-Weld Collection," with the name of the purchaser as well, which includes the Matsushimazu Byobu (Waves at Matsushima), a folding screen by Korin that is worthy of the national treasure designation.

10) Toa Bijutsushi ko, second part, Ernest Francisco Fenollosa et al. Fenollosa Shi Kinenkai, 1921 [509-1]

Photos on a page about the Rimpa school and Kano school: a painting by Korin and pottery by Kenzan

The original title is Epochs of Chinese & Japanese art : an outline history of East Asiatic design [K141-A16], which was translated by Fenollosa's students into Toa Bijutsushi ko.

He was a pioneer who systematically organized works from the Rimpa school, evaluating them highly as the Japanese school of impression.

The book explains that HON'AMI Koetsu, OGATA Korin, and OGATA Kenzan were famous in Europe and the United States at that time as founders of the Rimpa school. However, Fenollosa himself believed that TAWARAYA Sotatsu, who was unknown in Europe and the United States, also helped in forming the Rimpa school.

Fenollosa, who valued "the art of the common people" more than "aristocratic art," especially praised Koetsu among the Rimpa school artists, saying that he was the only artist in the Edo period who ranked with the great artists of the past, although the Rimpa school and the Kano school came from the art of "aristocrats," great feudal lords (daimyos) and their vassals. He thought "the school commonly spoken of as the ‘Коrin'...should be headed more properly with the name of Korin's teacher", Koetsu.

Impact on Japonisme and Art Nouveau

Japanese fine art spread to Europe thorough a series of international expositions held in Vienna and Paris during the latter half of the 19th century, and Japonisme was soon a popular trend. Composition using patterns of plants and the use of patterns using natural forms had a tremendous impact on European artists and were soon evident in the works of Impressionists. The decorative nature of works from the Rimpa school can be seen in the developments in European art that led to the emergence of the new form of design that became Art Nouveau.

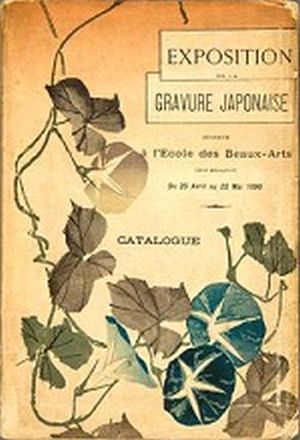

Catalog of the exhibition "Exposition de la gravure japonaise (Exposition on Japanese woodcuts)" planned by Samuel Bing (real name: Siegfried Bing, 1838-1905), central figure in the development of Art Nouveau

Art Nouveau and Rimpa school in modern Japan

ASAI Chu

Asai Chu (1856-1907) was a prominent painter who helped introduce European painting techniques to Japan during the Meiji period.

When he studied Western painting in Paris, he was fascinated by the Paris International Exposition and Art Nouveau. He understood that Japonisme was a factor in Art Nouveau, and found the Rimpa school at the root of it.

After moving to Kyoto in 1902, in addition to producing European-style paintings, he also created numerous handicraft designs.

He came up with designs not only in the Rimpa style, but also the Kano school style and yamato-e style, passing away before establishing his own design style.

11) Asai Chu gashu oyobi hoyden, ISHII Hakutei (ed.), Unsodo, 1929 [553-116]

This is a collection of ASAI's art with commentary by ISHII Hakutei, who studied painting under ASAI Chu. It was published 23 years after ASAI's death.

Asai's life from his birth to his later years in Kyoto is introduced, along with his works. According to this book, after returning to Japan, he lived in Kyoto as a Western-style painter, Japanese-style painter, and handicraft designer.

His handicraft designs show the influence of the Rimpa school in their motifs and rounded patterns.

KAMISAKA Sekka

KAMISAKA Sekka (real name: KAMISAKA Yoshitaka), who is considered the founder of the modern Rimpa school, felt different about Art Nouveau despite seeing the modernization of the West as ASAI did. KAMISAKA focused more on design than painting. In the process of modernizing traditional crafts, he studied HON'AMI Koetsu and OGATA Korin, and was very impressed by the uniqueness of the Rimpa school in terms of modeling. He encountered Art Nouveau during his visit to Paris and Glasgow, but maintained a negative view of it. He regarded Art Nouveau and Westerners' sense of Rimpa as fashion as a temporary fad, due to "the nature of Europeans, who run after novelty."("Kamisaka Sekka shi no Isho Kogei Dan (lit. Design Craft Talk By Kamisaka Sekka)", Zuan (図按) 2nd, 1902.2.25 [雑34-6])

Kamisaka inherited the sensibilities of the Rimpa school, traditional Japanese beauty characterized by soft colors and concise line drawings. As a handicraft designer, he displayed great skill in decorative design of products for everyday use, including kimonos, pottery, and lacquerware, and naturally carried out collaborations. It is said that Sekka has always aimed to collaborate when making products.

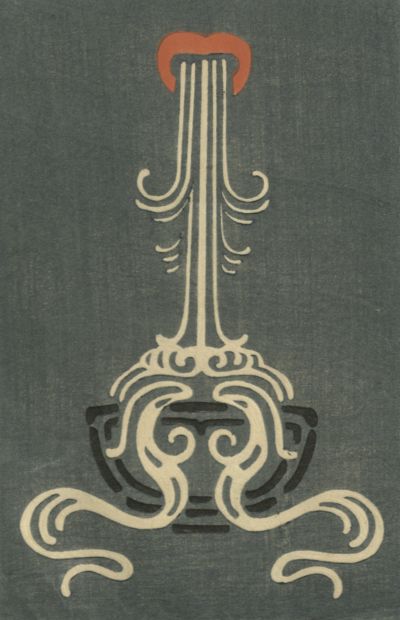

12) Kokkei Zuan (Collection of Humorous Designs), KAMISAKA Sekka, Yamada Unsodo, 1903 [83-230]

This book is a collection of multicolor woodblock prints published after his return from Europe. This collection reflects his view of Art Nouveau.

The titles of his designs are named after disparaging terms for Art Nouveau in Europe, such as "noodle style" and "macaroni art nouveau."

He himself called Art Nouveau "udon art," and in the design Macaroni art, he wrote, "This is not a fountain. Look at the udon noodles gushing out of the bowl like a fountain." He was ridiculing Art Nouveau.

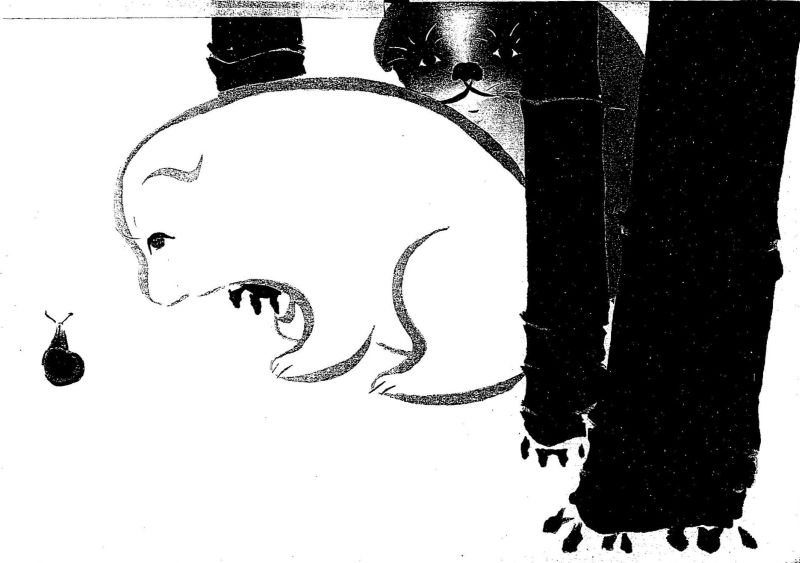

13) Momoyogusa (A World of Things), KAMISAKA Sekka, Yamada Unsodo, 1909-1910 [406-32]

Momoyogusa (A World of Things)is a collection of illustrations from which you can feel Kamisaka's progressiveness and warmth.

He was known as a pioneer in modern woodblock prints, and this design album is considered the culmination of his design work. The three volumes of this book contains his characteristic woodblock print designs, featuring sophisticated composition, exaggeration, and a wide variety of subject matter, including animals, plants, and scenes from daily life.

He studied the Rimpa school and incorporated its treatment of brush strokes and motifs in an orthodox manner.

In Morning glory, he employed a Japanese paint blurring technique called "tarashikomi." The composition of the morning glory peeking out from behind a bamboo lattice is unique. Compared to Bing's morning glory (catalog of the exhibition "Exposition de la gravure japonaise"), you can understand what he thought about the Rimpa school as a true form of traditional Japanese art.

Next

Appendix

Cute works of Rimpa in books