- Kaleidoscope of Books

- A Historical Tour of Department Stores in Japan

- Chapter 3: See, Eat, and Experience

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Let's Go to a Department Store: Where the Fashion is!

- Chapter 2: Shopping at Department Stores: A Place to Discover People and Things

- Chapter 3: See, Eat, and Experience: The Ways that Department Stores Make Shopping Fun

- Afterword/References

- Japanese

3 See, Eat, and Experience: The Ways that Department Stores Make Shopping Fun

- Wouldn’t you know it! Department stores are not just for shopping.

The upper floors house all kinds of attractions that will keep you entertained all day long.

Cultural Events

- Department stores often sponsor art exhibits, product fairs, concerts, and other cultural events all year-round.

Check it out!

Exhibitions that Bring Art into Your Daily Life

By the end of the Meiji era, department stores had begun to sponsor exhibitions of paintings, tea ceremony utensils, kimonos, local delicacies, and other products. These events were intended not just to attract customers but to promote sales by displaying merchandise in an attractive manner.

The first art exhibition hosted in a department store was an exhibition of Japanese paintings held in November 1908 at the Osaka Mitsukoshi.

The November issue of Mitsukoshi Times includes not only an advertisement for the exhibition but also a catalog with prices. The most expensive work shown was IMAO Keinen’s Kawasemi ni ashi (kingfisher in the reeds), which was priced at 24 yen. This was at a time when the starting salary for an elementary school teacher was between 10 and 13 yen.

The First Fashion Show in Japan

Japan’s first fashion show ever was held in Mitsukoshi Hall on the 6th floor of the Nihombashi Mitsukoshi in September 1927. According to Mitsukoshi magazine, three popular actresses, including the original MIZUTANI Yaeko, served as models and performed dances wearing kimonos with designs that were selected from patterns that were submitted by the public. Their kimonos were also displayed in an Exhibition of Fine Textiles, which was held at the same time.

Mitsukoshi Hall was the venue for numerous cultural events, including lectures and kabuki plays as well asl traditional Japanese dance and drama. Now known as Mitsukoshi Theater, it continues to host theatrical and musical performances even to this day.

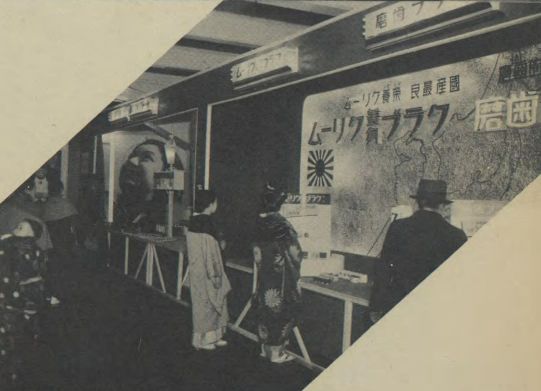

An Exhibition of Advertisements Reflecting the Times

Given the relative scarcity of libraries, museums, and other cultural facilities in Japan during the first half of the 20th century, it is not surprising that department stores began to play an important role in providing public access to cultural and artistic events as well as to other events related to topical subjects.

These photos are of an exhibition entitled Tomorrow’s Advertisements, which was held at the Matsuzakaya Ueno Store in 1938. The showroom window displays, advertisements, and posters that were exhibited garnered much public attention, Before the exhibition even opened, the displays were screened by a panel of judges, including stage designer ITO Kisaku, and prominent showroom window displays from major exhibitors were awarded prizes, including the Ministry of Commerce and Industry Cup.

It was the middle of the Second Sino-Japanese War, and it appears that the sponsors were concerned that a prolonged war would weaken the economy, so the exhibition was held to stimulate the interest of consumers.

Delicious Food in Department Stores

- There is nothing that works up an appetite like walking around a department store, is there?

So, it’s not surprising that many department stores also offer places to enjoy some delicious food while talking the things you’ve seen and purchased.

Free Samples to Help You Decide

After Shirokiya opened the first restaurant in a Japanese department store in 1911, it wasn’t long before more and more stores followed suit. And over time, as the floor space devoted to dining became larger, so too did the menus become more varied. By the end of the Taisho era, large dining areas occupying multiple floors appeared. And as these businesses evolved, they devised many technique that remain in use today.

For example, when Shirokiya opened the first restaurant, they implemented two innovations that are still common today. One is free samples of their food and the other is the use of meal tickets to purchase food. Shirokiya took a hint from delicatessens elsewhere in the world and began to displaying sample meals in glass cases near the entrance to the restaurant. Additionally, customers entering the restaurant were asked to pay in advance and received a meal ticket to give to their server. This resulted in a faster turnover rate of customers and four times as many sales. Shirokiya’s methods were quickly adopted not only at other department stores but in restaurants all over Japan.

The book Tokyo meibutsu tabearuki is an anthology of reviews of the food at restaurants and department stores in Tokyo. These popular reviews were originally published serially in the Jijishimpō, predecessor of today’s Mainichi Shimbun, and often contained humorous descriptions of customers who stand before the display cases at the front of the Matsuya Ginza store and wonder absentmindedly what to order.

As Tokyo was rebuilt in the aftermath of the Great Kanto earthquake, the number of restaurants, especially those in department stores, increased rapidly. Here is a photograph of a department store restaurant with an insert of its sample display case. The elegant atmosphere and realistic food samples give testament to just how eagerly department stores focused on developing their food businesses.

Rules for Serving Staff

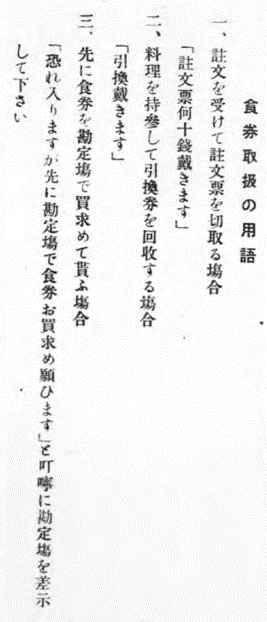

This excerpt from Dai Hankyu shows the section on meal tickets from a training manual for the waitstaff at Hankyu Department Store restaurants.

The manual describes a variety of situations involving customers are to be handled, including serving meals and retrieving meal tickets, customers who order food without first purchasing meal tickets, and being asked to cash in meal tickets. At the time, waitstaff were considered the face of Hankyu Department Stores and underwent strict training, because their actions directly affect customer satisfaction.

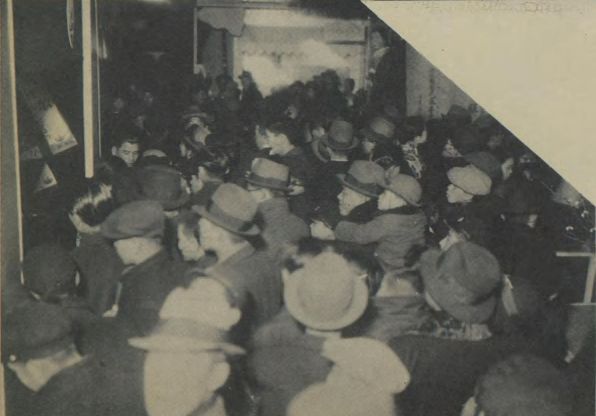

The Hankyu restaurants were so popular in those days that a 3,000-seat restaurant would be filled with customers on holidays. This manual is evidence of just how important polite service was considered even during crowded hours.

A View of the City from the Rooftop

- Once your stomach is full, it’s time for some fresh air.

There is many a great view of the surrounding cityscape from the rooftops of Japanese department stores. At the end of the day, there’s relaxation and pleasure to be had in equal measure up on the roof.

Relaxation in the Rooftop Garden

In 1907, Mitsukoshi became the first department store in Japan to open its “rooftop garden” to customers. The western-style garden included flower beds, wisteria trellises, ponds, and fountains as well as a shrine dedicated to Mimeguri-Inari, which was closely associated with the founder of the Mitsui family.

At the same time, other department stores began to utilize their rooftop space, such as the refreshment stand and bonsai garden that formed Shirokiya’s rooftop garden.

Given that high-rise buildings were still a rarity at the time, the view from the rooftop was a great selling point for department stores.

The Osaka Mitsukosi had a tea house on its roof garden. Known as the Ryoun-tei, it was built on the 9th floor roof, facing Osaka Castle, and people could see as far as east Osaka.

NOZAKI Kota was not only the person responsible for the expansion and renovation of the Osaka Mitsukoshi, but he was also an expert on the tea ceremony. Known by the name “Gen-an,” he kept careful notes about the many tea ceremonies in which he participated.

Vigorousness and Delightfulness: Rooftop Amusement Park

The advent of steel-framed, reinforced-concrete construction made it possible to better use rooftop space. Department stores each installed unique facilities on their rooftops, including amusement parks, roller skating rinks, event stages, and even concert halls.

The Matsuya Asakusa, which opened in 1931, was very successful attracting families to its rooftop “Sports Land,” which included a small zoo, a bowling alley, a baseball field, a shooting gallery, and other sports parks and gathered a lot of family groups.

This photo shows a cable car that ran from one ends of the rooftop to the other at the Matsuya Asakusa. Designed in imitation of the cable cars at Niagara Falls, it featured an impressive view of the surrounding city and a key attraction.

The mini locomotive shown here cost 10 sen (one-tenth of a yen) for two times around the park and was the most popular attraction with children. The crowd of people at trackside are no doubt adults watching their children riding the locomotive.

Next

Afterword/References