- Kaleidoscope of Books

- Parties under the Cherry Blossoms in Edo

- Chapter 3: Hanami customs

- Introduction

- Chapter 1: Cherry blossom viewing spots

- Chapter 2: Varieties of cherry blossoms

- Chapter 3: Hanami customs

- References

- Japanese

Chapter 3: Hanami customs

It is notable that hanami was widely enjoyed as popular entertainment, regardless of social class or gender, in Edo. MITAMURA Engyo (1870-1952), an independent scholar of the culture in Edo, wrote as follows: “It is said that common people were placed in a lower status than samurais, or that workers lived from hand to mouth in Edo. Nevertheless, they knew the way to live happily and merrily.” (Mitamura Engyo, Edo nenchu gyoji, 1927, p.621. [565-52]). As he said, in the hanami that people enjoyed apart from their hard daily lives, we really see the essence of the common culture in Edo. This chapter takes up the customs of hanami in the Edo period, and guides you to the “joyful city Edo” (Mitamura).

Nezumi hanami

Although the picture above is from a facsimile book, the original woodblock print is thought to have been published in the Kyoho era (1716-1736). This work portrays three flower viewing spots in Edo: Kameido (where plum blossoms and wisteria flowers were popular), Asakusa and Ueno. It seems to be a kind of hanagoyomi, introduced later. We can see how the people in Edo enjoyed hanami because this work depicts the customs of hanami of every social class, although all the figures are drawn as mice. It is unclear why humans were depicted as mice, but one theory says that the painter praised the prosperity of Edo by likening it to the vigorous fertility of the small animals. The painter’s life, career and background are unknown today.

Eve of a hanami

It is hard to fall asleep at night before going on vacation. For the people in Edo, hanami was a once-a-year pleasure which they enjoyed in the suburbs for a day, away from the overcrowded city under the strict control of the shogunate officials. On the evening before a day of hanami, the whole family prepared for it with excitement.

Senryu nenchu gyoji

NISHIHARA Ryuu, edited, Senryu nenchu gyoji, Shunyodo, 1928. [911.4-N82ウ]

This anthology was edited by a notable scholar of senryu, a type of short poetry similar to haiku written in the Edo period. According to the preface, the editor intended to clarify annual events in Edo for around 100 years from the Horeki era (1751-1764) to the Tempo era (1830-1844) by compiling collected senryu on each subject. To that end, he researched thousands of works on senryu and collected without excluding stupid or bad pieces. From the section on hanami, we quote some works about the eve of hanami as follows.

◇ The eve of a hanami

Hanged monks are

Here, there and everywhere

―Of course this is not a scene of mass murder. Hanged monks refers to teru teru bozu, a talisman to bring good weather, shaped like the robe of a Buddhist monk and hung in a window.

◇ She says

“Let’s go to a theatre if it rains”

When she prepares a feast

―Along with hanami, plays were entertainment for a whole day for the people of Edo, and they went to theatres with luxury lunch boxes, like hanami.

◇ When a feast is ready

Beauty of woman is

Not ready yet

―Women took a lot of time to dress themselves carefully.

◇ Blossoms in the rain

They deeply regret

Because of makeup without sleeping

―If it rains, it will be a waste of time for women to have down their makeup.

◇ The morning of hanami

Even the female servants are

Also to be praised

―In the morning on the day of hanami, the family dressed even their servant beautifully and went out.

Hanagoyomi, the calendar of flowers

In the Edo period, many guidebooks were published. People went out for hanami with guidebooks such as meisho zue, literally an illustrated guide to highlights, which introduces highlights and historic sites and explains the history of temples and shrines in the city, or, hanagoyomi, literally a calendar of flowers, which introduces the best times and viewing spots of flowers in each season.

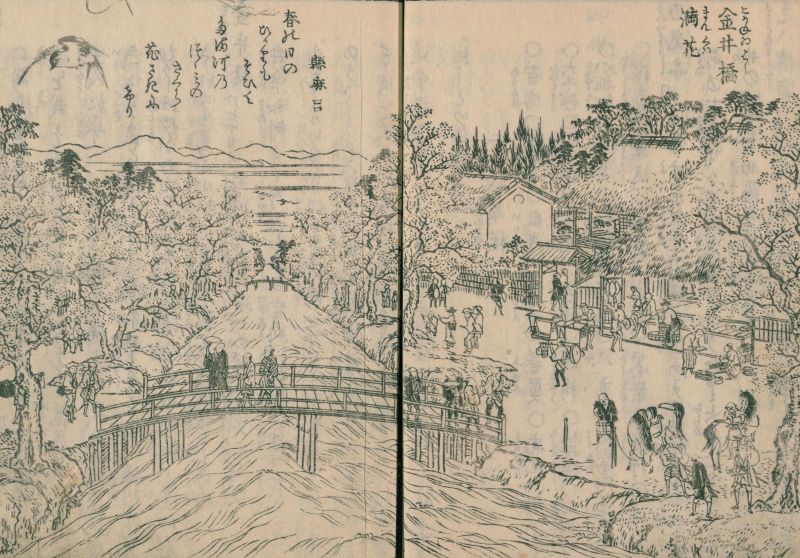

Edo yuran hanagoyomi (4 vols.)

This work was also mentioned in Chapter 2. It can be called the best hanagoyomi in the late Edo period. The section on cherry blossoms describes famous cherry trees such as Shushiki-zakura (leaf 11), which we explain later, introduces notable poems and stories about cherry blossoms, and even introduces restaurants and bars at each cherry blossom viewing spot. The content is comparable to a travel guidebook today. The picture shown above depicted a hanami at Koganei Bridge, as introduced in Chapter 1.

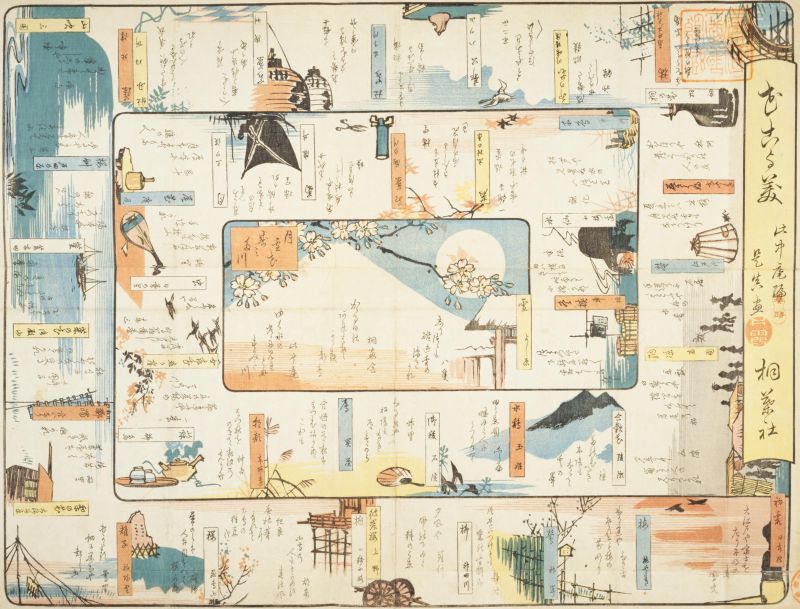

Hana koyomi

This is a sugoroku board game, which uses hanagoyomi as the subject. The painter is SHIBATA Zeshin (1807-1891), an artist from the final years of the Edo period to the Meiji era. Each square depicts a flower viewing spot, with poems on each one. In the bottom center, we can see cherry blossoms in Ueno and Asukayama. This board game is included in the collection of sugoroku housed in the NDL, which contains some other games depicting flower viewing spots, such as Edo meisho shiki yusan sugoroku, Shinban kyoka edo hanami sugoroku, and Edo meisho kakiwake hokku sugoroku.

Amusements along the road

The NDL provides the Historical Recordings Collection, digitized recordings produced up to the 1950s in Japan. You can listen to recordings of oral storytelling by notable performers of rakugo, a form of traditional verbal entertainment, via this internet service. A rakugo story in the collection, under the title Nagaya no hanami, depicts residents living in a nagaya (poor tenement houses in Edo) walking to hanami, carrying a barrel filled with tea instead of liquor, and jubako boxes filled with yellow radish pickles instead of omelets and sliced radish instead of kamaboko (processed seafood). Just as the poor people tried to make cheap food look like a feast in this comical story, the people in Edo brought elaborate feasts for hanami once a year.

A group going to hanami would have two people carry their liquor barrels and food, and played a game in which the people carrying them would change if they passed a monk along the way. When hand games became popular, people played them while walking.

Kiyu shoran (12 volumes and an appendix)

KITAMURA Nobuyo, Kiyu shoran: 12 kan fu 1 kan, pt.2, Kondo Kappansho, 1903. [031.2-Ki297k]

Would you like to know what were in those boxed feasts? This work may give a clue about them. It was written in the late Edo period and consists of 12 volumes and an appendix. The author excerpted and examined descriptions about daily customs in the Japanese and Chinese literature that he had read over many years. It is a useful work for understanding daily lives in the Edo period. The first half of volume 10 deals with cuisine, widely examining every aspect of the food culture such as ingredients, recipes, names of dishes, and even reviews of restaurants, party manners, and famous confectioneries. It also includes a description of caterers. The people in Edo may have also used catering services for a hanami feast.

Kensarae sumai zue (2 vols.)

The hand games in the Edo period, which originated from China and came to Japan via Nagasaki in the Genroku era (1688-1704), spread all over the country and were divided into various forms. The games involved simultaneously moving fingers while calling something out, and can be roughly divided into two types. One type is number guessing games, and the other is sansukumi games (deciding victory or defeat using three shapes). The janken (rock-paper-scissors) that we currently play is one of the latter. Although the games were played for amusement at drinking parties, after the games became popular people held hand game tournaments (kensarae sumo) resembling sumo tournaments (see pictures 9, 10, and 11).

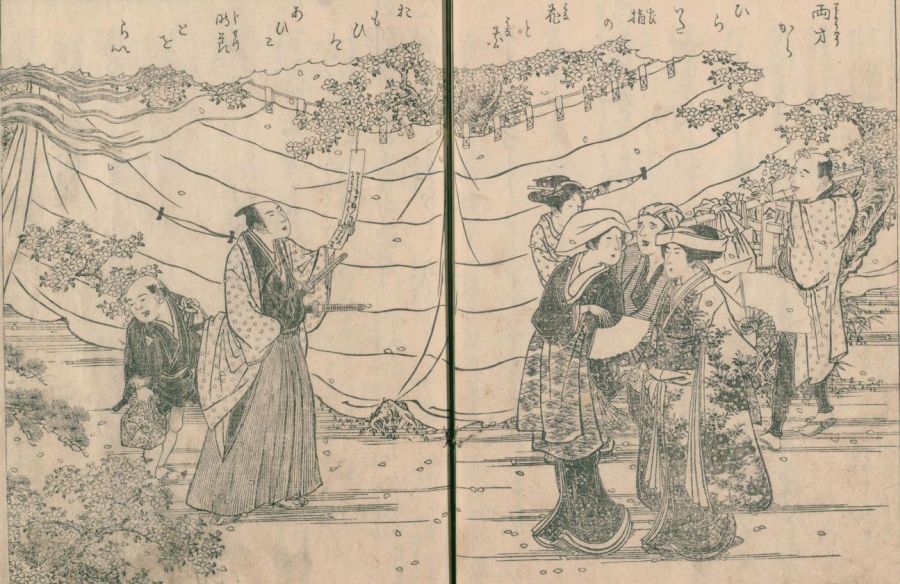

This work was an introduction to hand games, published in 1809, which described the attitude toward playing and the rules of the games. The content includes various game names, such as shoyaken (landowner game), mushiken (insect game), and taiheiken (peace game). In the hand game tournaments, players mainly played shoyaken. This game uses three shapes, called “landowner,” “hunter,” and “fox,” and is also known as kitsuneken (fox game) or tohachiken (game invented by Tohachi). The picture shown above is an illustration of hanami, inserted in the section on the attitude for playing hand games.

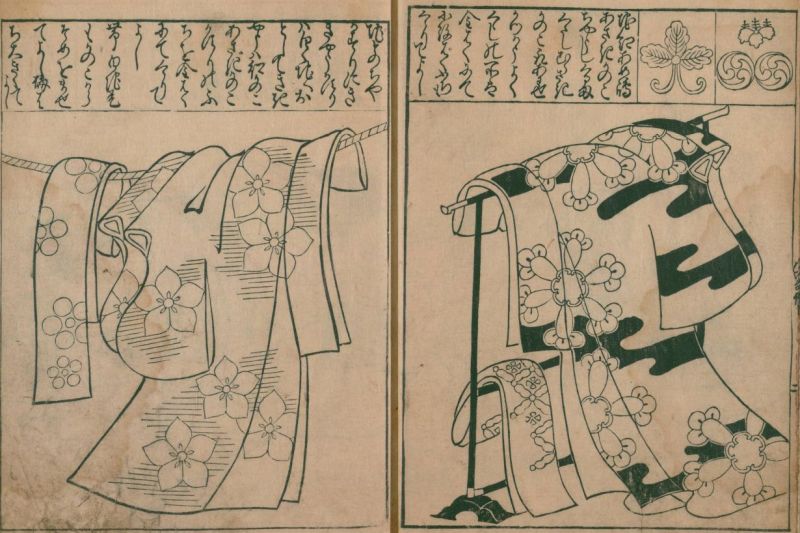

Hanami kosode, the outfit for hanami

Women dressed up to go out for hanami. Their outfits were called hanami kosode (hanami garment). According to a local Edo gazette in 1714, Murasaki no hitomoto [寄別5-2-3-1] by TODA Mosui (1629-1706), women dressed up more for hanami than for new year parties (leaf 47). The author explained that for the common people in Edo, if it rained at hanami, it was even stylish to let their gorgeous dresses get wet without using umbrellas. He also described that each hanami seat was separated by curtains, but some hanami visitors used to pass the rope used to tie up their luggage through the sleeve of their outerwear and hang it on the branches of the cherry trees instead of a curtain. Colorfully decorated clothes fluttering in the wind with scattered cherry blossoms... What a beautiful sight!

Tosei soryu hiinagata (2 vols.)

In the Edo period, many design collection books were published, which were called hinagata-bon (or, hiinagata-bon). These materials are valuable for understanding the fashion at that time. This work is a hinagata-bon on patterns for kosode outerwear in 17th century, which was painted by HISHIKAWA Moronobu (1618-1694), who is said to be the founder of ukiyo-e.

Cherry blossoms at the Sumida River by YOSHU Chikanobu

This nishiki-e painted in the Meiji era depicts the bank of the Sumida River crowded with hanami visitors. It seems to be a scene from the Edo period, based on the clothes worn by the people shown. Behind the beautifully dressed women, there are people drinking, playing instruments, dancing, and enjoying an amateur play. We can imagine the scenery of hanami in Edo from this picture.

School excursion for hanami

The children of the common people in Edo studied reading and writing in private educational institutions known as terakoya schools. Since the middle of the Edo period, the teachers of terakoya schools took their students out for hanami. They dressed up with uniform parasols and handkerchiefs, and some groups had over 100 students. In Edo at that time, the attendance rate in education was high and many terakoya schools competed to enroll students. It is thought that the school hanami excursion was to promote the school as well as a demonstration to gain an advantage over other schools. Later, teachers of singing and dancing, haiku masters, and even trainers of apprentice geishas in Yoshiwara began to take their disciples out for hanami.

Hanami at Asukayama, one of the highlights of Edo, by Hiroshige

Hiroshige, who was the most notable ukiyo-e artist in the late Edo period, is highly acclaimed for his depictions of landscapes, and drew many pictures of famous locations in Edo and its suburbs. The picture above is a scene of hanami at Asukayama, featuring young girls with uniform dresses and parasols, so it seems to depict a terakoya school excursion to hanami. Although a school excursion with uniform dresses would make them feel a sense of belonging to their group, some parents were dissatisfied because of the heavy cost.

Hanami at the Sumida River by Kuniyoshi

This picture was painted by UTAGAWA Kuniyoshi, a popular ukiyo-e artist in the late Edo period. He featured a group that seems to be parents and children with uniform parasols walking along the Sumida River and other hanami visitors watching the beautifully dressed group. It is unclear whether they were on a school excursion or not, but this picture helps us imagine hanami with a group.

Literary art at hanami

From ancient times, Japanese people entertained themselves at hanami with literary art such as waka (classical Japanese poetry), kanshi (classical Chinese poetry), or renga (Japanese collaborative poetry). For example, Section 82 of the Tales of Ise depicted ARIWARA no Narihira (825-880), a notable poet in the 9th century, going to hanami with his friends and enjoying exchanging waka poems on the subject of cherry blossoms without even looking at the ones blooming in front of them (Ise monogatari, 1608. [WA7-238]). The people in Edo also entertained themselves with literary art at hanami. The intellectuals composed classical Japanese and Chinese poetry, and the common people wrote haiku, the popular new style of Japanese poetry.

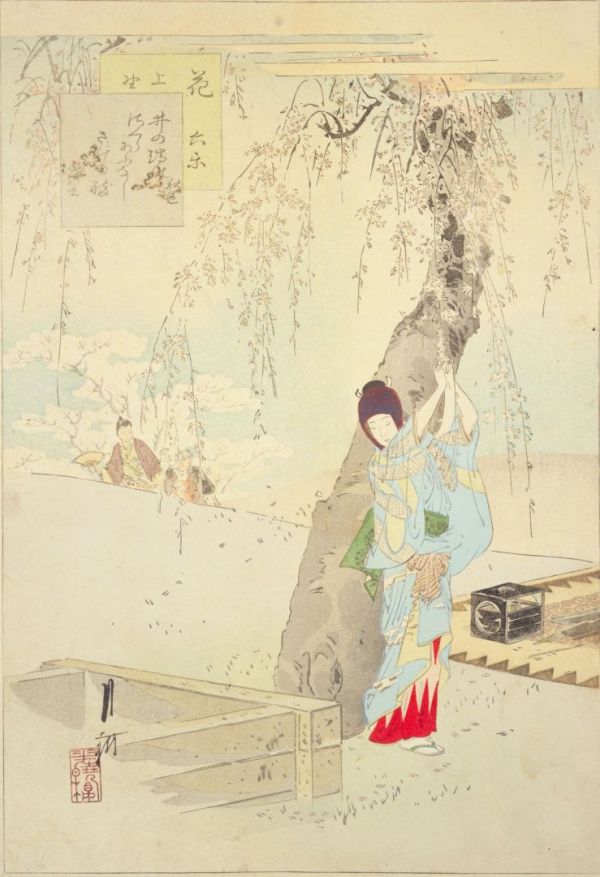

Cherry blossoms in Ueno by OGATA Gekko

This picture is a nishiki-e painted by OGATA Gekko (1859-1920), a famous artist in the Meiji era. It depicts the story of a cherry tree called Shushiki-zakura. This story is as follows: A long time ago, there lived a girl whose name was Oaki, a daughter of a confectioner in Nihombashi Koamicho (in present-day Chuo-ku, Tokyo). When she was 13 years old, she went to Ueno for hanami and wrote a haiku about a cherry tree beside a well.

Beside a well

Cherry blossoms are danger

Because of drunkenness

Her haiku became popular, since it was highly appreciated even by the abbot of Kan’ei-ji temple in Ueno, who was a prince of the imperial family from Kyoto and the most respected nobleman in Edo. Later, she became known as a famous poet whose pen name was Shushiki. Edo yuran hanagoyomi introduced her haiku in the section on cherry blossoms. It was first published in volume 3 of Edo Sunago, a local Edo gazette by KIKUOKA Senryo (1680-1747) in 1732 (Kikuoka Senryo, Tanji Shochi, rev., Edo Sunago, 1772. [840-1]).

Hanami in April, by KEISAI Eisen

This picture was painted by KEISAI Eisen (1791-1848), an ukiyo-e artist and writer in the late Edo period. A woman ties a tanzaku, a strip of paper with a haiku written on it, on a branch of a cherry tree. She may be a geisha. A man gets down on all fours and becomes her stepping stone. Women tying tanzaku were often used as the subject of ukiyo-e.

Chaban, amateur theatre

Chaban was a type of parody theatre, which originated from performances by apprentice actors during breaks in the final programs of kabuki theatre, and later came to refer to improvisational plays by amateurs. In the late Edo period, people widely performed chaban plays at hanami, not only to entertain their families and friends but also to surprise other hanami visitors and receive applause.

Mime on a chaban play at an indoor party, by Toyokuni III

In this picture, a man, wears a fake courtier’s cap made from a bowl with a long piece of paper pasted to it and wields a bamboo imitation sword, pretending to be a kabuki actor playing a famous scene. Although the picture depicted a chaban play at an indoor party, it seems that outdoor chaban plays at hanami were also similar. The painter UTAGAWA Toyokuni III (1786-1864), who first called himself Kunisada, is known for his prolificacy, and is said to be the ukiyo-e artist who left the most works.

Hanagoyomi Hasshojin

RYUTEI Rijo, FUKAGAWA Baien, revised, Hanagoyomi Hasshojin, Ito Kurazo, 1891. [特11-459]

This work was a series of kokkei-bon (comical novels), published from 1820 to 1849 and written by RYUTEI Rijo (died 1841), which was handed down after his death to other writers, such as Ippitsuan Shujin (Keisai Eisen’s penname as a writer). It is a comedy about eight layabouts who go to the highlights in Edo each season, perform chaban plays and make a funny failure of it. Volume 1 is about hanami at Asukayama. They perform a chaban play of vengeance, but the one who will play the role of arbitrator for the duel does not arrive, because his family has stopped him from leaving home. There is no choice but to continue the play, so the two duelists state their reasons for revenge and pretend to fight with imitation swords. A samurai misunderstands this as a real duel, and pulls out his sword to offer his assistance in taking revenge, so the chaban players run away in surprise. This story is the basis of a rakugo story called hanami no adauchi (Vengeance at hanami), or Sakuranomiya (Cherry Blossom Park).

Drinking at hanami

As it is today, drinking was the biggest pleasure at hanami. The people in Edo had endless fun drinking while playing instruments and watching funny chaban plays. Sometimes drunkards’ behavior was frowned on, as a poem collected in Senryu nenchu gyoji describes:

Like a spoiled child

A man is pulled away

Evening at hanami

MITAMURA Engyo said that since the Tokugawa shogunate had a policy of overlooking the behavior of common people at hanami, the officials did not try to actively keep an eye on them (Mitamura Engyo, Goraku no Edo, 1925, p.17. [546-37]).

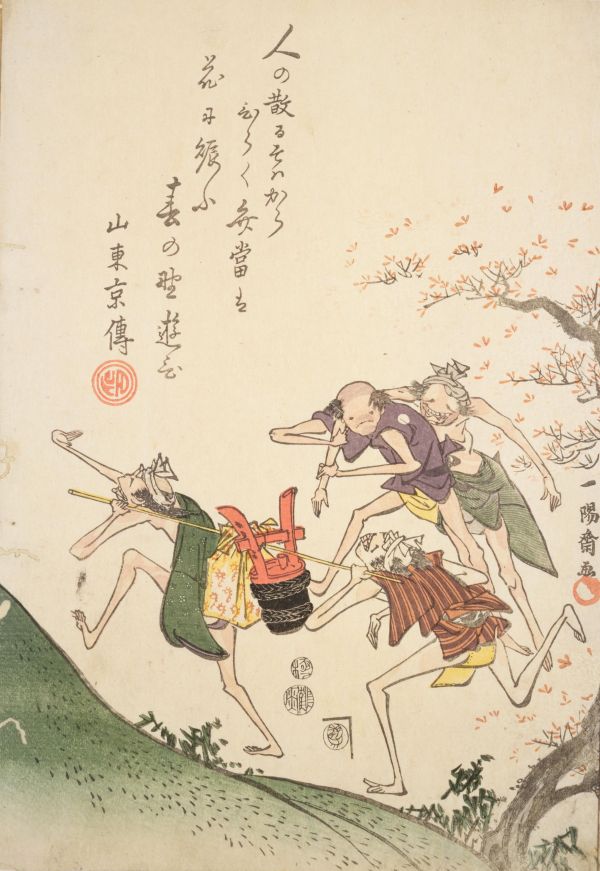

Hanami in April, by Toyokuni

In the classical rakugo story hanamizake (Drinking at hanami), there are two men who have no money. To sell liquor at a hanami spot and make money, they buy a barrel of liquor on credit. They don’t even have coins to make change, so they borrow them from the liquor store as well. On the way, one of them wants a drink, so he gives the borrowed coins to his partner and drinks a glass of liquor. The other one also wants to drink, so he returns the coins he received and drinks a glass too. The coins go back and forth between the two, and the liquor barrel becomes completely empty by the time they arrive at the hanami spot. Of course, they have only the coins they originally borrowed for change and the debt on the payment for the barrel. This funny picture makes us imagine this story. The painter UTAGAWA Toyokuni (1769-1825) signed one of his names, Ichiyosai, on this picture. He was a disciple of UTAGAWA Toyoharu (1735-1814), and became popular for his pictures of beautiful women and actors. The notable writer SANTO Kyoden (1761-1816) wrote text in the margin.

Bank of the Sumida River in April, by Hirokage

This picture is one of the nishiki-e series called Edo meisho doke zukushi (Collection of clowns in famous spots in Edo), which depicts people in Edo behaving comically. There are many pictures with hanami as the subject, probably because it was an opportunity for the common people to let themselves go. The painter is UTAGAWA Hirokage, who has no known detailed background but is said to be a disciple of Hiroshige. He left a few works including this series, known as his representative work.

Souvenir of hanami

Just like us today, the people in Edo were also familiar with sakuramochi, a traditional Japanese confection made with cherry leaves. The sakuramochi in the Kansai region (the region including Osaka and Kyoto) is a round rice cake made of coarsely ground sticky rice with red bean paste (anko) inside and wrapped in a pickled cherry leaf. Kiyu shoran, the cultural encyclopedia introduced above, called the Kansai-style one domyoji. On the other hand, the confection known as sakuramochi in the Kanto region (the region including Edo) is made by stretching wheat flour dough into long strips, sandwiching red bean paste between them and pasting a cherry leaf on top. In the Edo period, Kanto-style sakuramochi made by a confectioner in front of Chomei-ji temple in Mukojima, Sumida was popular, and it is still familiar as a specialty of Tokyo even today. It was made and sold by YAMAMOTO Shinroku, who was a gatekeeper of Chomei-ji temple, using cherry leaves from the bank of the Sumida River, and was often bought by hanami visitors as a souvenir.

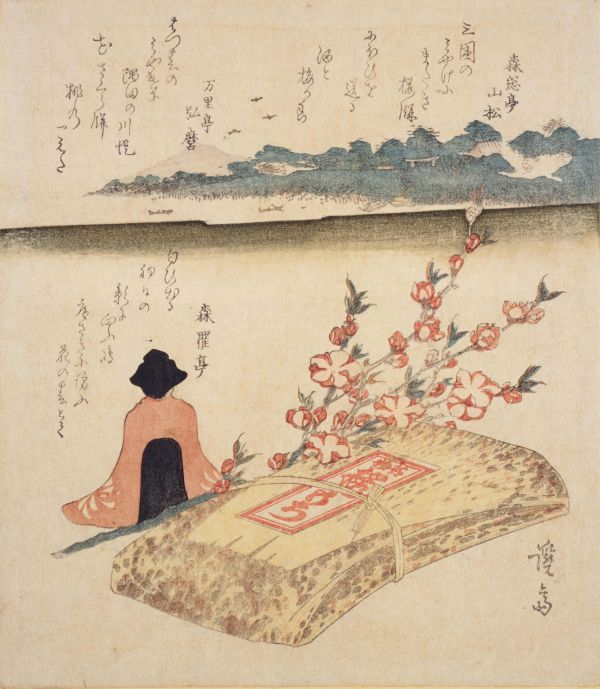

Sakuramochi as the souvenir from Mimeguri, by Keisai Eisen

This picture was painted by KEISAI Eisen. Mimeguri Inari is a Shinto shrine located beside the bank of the Sumida River and 300 meters southeast of Chomei-ji temple. The confection may be a souvenir from hanami. A branch of cherry blossoms is attached to it.

Next

References