- Top

- > Part 1: Early modern times

- >1: Achievements of traditional pharmacognosists and birth of Dutch studies

Chapter 3 Eyes of science Achievements of traditional pharmacognosists and birth of Dutch studies

Achievements of traditional pharmacognosists and birth of Dutch studies

Pharmacognosy is pharmacology of Chinese origin which studied morphology, locality and effects of plants, animals, and minerals that can be used for medicinal purposes. It had its efflorescence in Japan during the Edo period, becoming more than just translating and interpreting of Chinese pharmacognosy texts and evolving into studies of animals and plants indigenous to Japan. Moreover, the Western studies brought in through the Netherlands, the only trading partner of the Western countries during the seclusion, was named rangaku and had tremendous influence on fields such as medical science, astronomy and military science.

ONO Ranzan, 1729-1810

A traditional pharmacognosist who was born in Kyoto. Ranzan engaged in research and fostering of younger generations at a private school until he was invited by the Shogunate to Edo at the age of 71 to become a lecturer in the Shogunate Medical School. The best-known literary work of Ranzan is the 48 volumes of Honzo komoku keimo (lit. Transcript of lectures on the Honzo Komoku, 1803-1805), which was a series of lecture transcripts on Honzo komoku (lit. Compendium of Materia Medica, Bencao gangmu in Chinese) written by Li Shizhen in the Ming dynasty, and is considered to be the most complete text for pharmacology during the Edo period. Ranzan’s co-authored work with Shimada Mitsufusa titled Kai (lit. Selected Flowering Plants) was considered to be the pioneer of scientific pictorial books of flora in Japan, and was later translated info French. Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold once described Ranzan as the “Carl von Linné of Japan”. Ranzan had over 1,000 pupils all over Japan, including Philipp Franz Balthasar von SieboldKimura Kenkado, Iwasaki Kan’en , and Mizutani Toyobumi (a.k.a. Sukeroku).

A traditional pharmacognosist who was born in Kyoto. Ranzan engaged in research and fostering of younger generations at a private school until he was invited by the Shogunate to Edo at the age of 71 to become a lecturer in the Shogunate Medical School. The best-known literary work of Ranzan is the 48 volumes of Honzo komoku keimo (lit. Transcript of lectures on the Honzo Komoku, 1803-1805), which was a series of lecture transcripts on Honzo komoku (lit. Compendium of Materia Medica, Bencao gangmu in Chinese) written by Li Shizhen in the Ming dynasty, and is considered to be the most complete text for pharmacology during the Edo period. Ranzan’s co-authored work with Shimada Mitsufusa titled Kai (lit. Selected Flowering Plants) was considered to be the pioneer of scientific pictorial books of flora in Japan, and was later translated info French. Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold once described Ranzan as the “Carl von Linné of Japan”. Ranzan had over 1,000 pupils all over Japan, including Philipp Franz Balthasar von SieboldKimura Kenkado, Iwasaki Kan’en , and Mizutani Toyobumi (a.k.a. Sukeroku).![]()

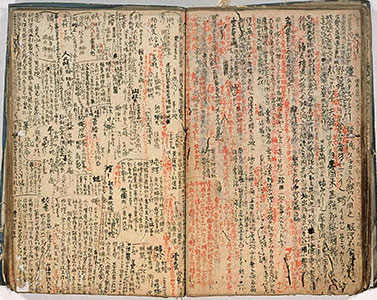

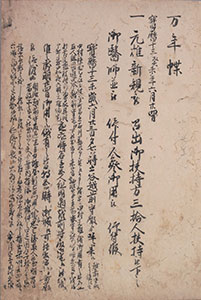

23 Honzo komoku soko, [mid-Edo period][WA1-10-6] Important Cultural Property

A collection of memoranda Ranzan had used for his lectures on Honzo komoku. Ranzan had written notes on every blank space and margin available and even cut open double-leaved pages to utilize the backs of each leaf, in addition to attaching a total of 346 slips of paper with memoranda on each. The initial creation continued until around 1780, and Ranzan kept on using these for about thirty years until his death, while revising with new supplements and corrections as they came up. Although records made by pupils who attended the lectures can be commonly found, memoranda for lectures created by and for the lecturer are rarely found.

KIMURA Kenkado, 1736-1802

A wealthy merchant in the brewing industry in Osaka, and was also known as a scholar and a naturalist. He utilized his wealth to collect books from both inside and outside Japan as well as specimens of shellfish of foreign origin. As for the traditional pharmacognosy aspect, Kenkado studied under the tutelage of Ono Ranzan, and authored works such as Ikkaku sanko (lit. Collected Information on Unicorn)

A wealthy merchant in the brewing industry in Osaka, and was also known as a scholar and a naturalist. He utilized his wealth to collect books from both inside and outside Japan as well as specimens of shellfish of foreign origin. As for the traditional pharmacognosy aspect, Kenkado studied under the tutelage of Ono Ranzan, and authored works such as Ikkaku sanko (lit. Collected Information on Unicorn)![]() and Kibai zufu (lit. Illustrations of Strange Shells)

and Kibai zufu (lit. Illustrations of Strange Shells)![]() . Known for his erudition and extensive knowledge as well as his large circle of friends, Kenkado associated with scholars such as Katsuragawa Hoshu and Otsuki Gentaku, as well as the lord of the Bungo Saiki Domain and the famous book collector Mori Takasue, and other feudal lords including Matsura Seizan, who was the lord of the Hirado Domain and the author of the essay collection titled Kasshi yawa.

. Known for his erudition and extensive knowledge as well as his large circle of friends, Kenkado associated with scholars such as Katsuragawa Hoshu and Otsuki Gentaku, as well as the lord of the Bungo Saiki Domain and the famous book collector Mori Takasue, and other feudal lords including Matsura Seizan, who was the lord of the Hirado Domain and the author of the essay collection titled Kasshi yawa.

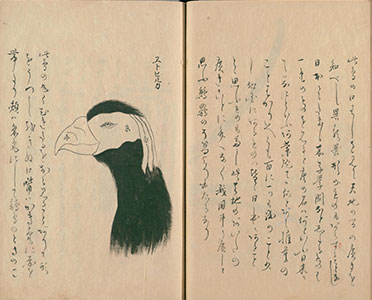

24 Kenkado zasshi, [mid-Edo period][WA21-16]

Kenkado zasshi consists of 48 articles on commodities, animals and plants, accompanied by short passages and illustrations. The inserted part depicts a bird from the northern region named “Etohiruka (Etopirika)”.

In 1785, an expedition was sent to Ezochi (present Hokkaido) by order of Tanuma Okitsugu, who was a roju (chief vassal of the Shogunate). In addition, Adam Kirilovich Laksman from Russia had visited Japan in 1792, increasing the interest towards Russia and the northern region at the time. Osaka had become the distributing center for the products from Ezochi, therefore Kenkado also collected maps and products of Ezochi and became well informed about Ezochi-related information.

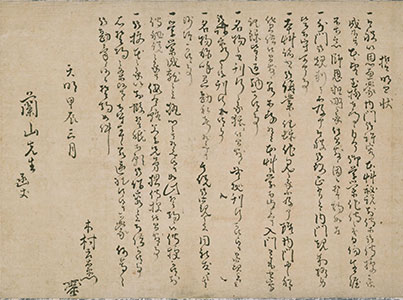

24 Related material: Kimura Kenkado seimeijo, 1784[WA1-10-7] Important Cultural Property

The oath written by Kenkado, when he was accepted as pupil by Ono Ranzan in 1784. The content is very strict, for example, requiring him to “return all notes and records copied since the admission in case of giving up the traditional pharmacognosy studies”. It is a similar type of document to Ukeigoto of Motoori Norinaga, but shows significant differences in its style of handwriting as well as contents. ![]()

TAMURA Ransui, 1718-1776

Ransui had started out as a town doctor, but his achievements in the cultivation of ginseng and other projects won recognition from the Shogunate, which then appointed him to be the director of the ginseng processing factory to be in charge of its domestic production. Ransui also took part in a nation-wide sampling of medicinal plants and surveys on products from numerous domains, which he visited by order of the Shogunate. People Ransui had close relationships with include Tanuma Okitsugu, who was a roju (chief vassal of the Shogunate), Shimazu Shigehide, who was the lord of the Satsuma Domain, and Kimura Kenkado. His first and second sons, Yoshiyuki and Kurimoto Tanshu, were both Shogunate doctors and naturalists. His pupils include Hiraga Gennai.

Ransui had started out as a town doctor, but his achievements in the cultivation of ginseng and other projects won recognition from the Shogunate, which then appointed him to be the director of the ginseng processing factory to be in charge of its domestic production. Ransui also took part in a nation-wide sampling of medicinal plants and surveys on products from numerous domains, which he visited by order of the Shogunate. People Ransui had close relationships with include Tanuma Okitsugu, who was a roju (chief vassal of the Shogunate), Shimazu Shigehide, who was the lord of the Satsuma Domain, and Kimura Kenkado. His first and second sons, Yoshiyuki and Kurimoto Tanshu, were both Shogunate doctors and naturalists. His pupils include Hiraga Gennai.

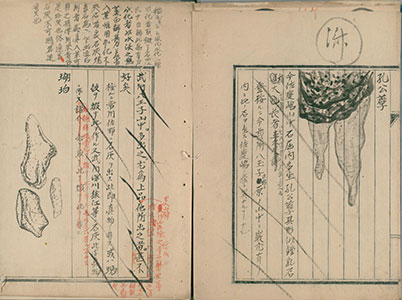

25 Nihon shoshu yakufu, [ca. 1751-1764][寄別11-5]

An excerpt from the draft of the book Ransui authored, titled Nihon shoshu yakufu. Ransui had put the character for “done” on the margin or wide slash lines, to mark where the revising and transcribing process are done on the draft. The contents only covers rocks, metals and hot springs, and no plants or animals. The book was passed down to the grandchild of Ransui’s son, Kurimoto Tanshu, and was eventually given to Ito Keisuke.

IWASAKI Kan’en, 1786-1842

An apprentice of Ono Ranzan. Kan’en was serving as a kachi, the lowest rank of samurai until he was discovered by Hotta Masaatsu, who was a wakadoshiyori (junior councilor of the Shogunate). Consequently, Kan’en was given opportunities to utilize his talent in projects such as writing for the vegetation part of Kokon yoranko (series of encyclopedic books that compiled and classified similar items from various literature), which was a government project ordered to Yashiro Hirokata, and being permitted to establish a medicinal-herb garden. Kan’en’s representative works include Japan’s first full-fledged colored pictorial book of flora titled Honzo zufu.

An apprentice of Ono Ranzan. Kan’en was serving as a kachi, the lowest rank of samurai until he was discovered by Hotta Masaatsu, who was a wakadoshiyori (junior councilor of the Shogunate). Consequently, Kan’en was given opportunities to utilize his talent in projects such as writing for the vegetation part of Kokon yoranko (series of encyclopedic books that compiled and classified similar items from various literature), which was a government project ordered to Yashiro Hirokata, and being permitted to establish a medicinal-herb garden. Kan’en’s representative works include Japan’s first full-fledged colored pictorial book of flora titled Honzo zufu.

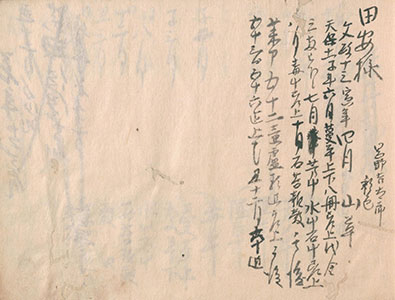

26 Honzo zufuki, [late Edo period][特1-2972]

A memorandum created on the occasion of the distribution of Honzo zufu. It records the dates and numbers of copies distributed to various places, including the copies presented to the Shogunate. The inserted part is the record of copies distributed to the Tayasu Family, which was one of the three junior collateral houses of the Tokugawa Family. ![]()

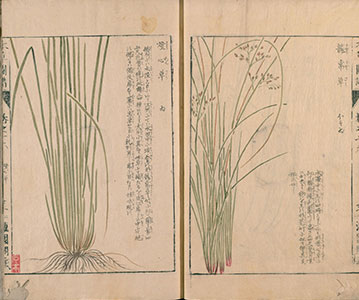

26 Related material: Honzo zufu, vol. 16 (out of vols. 5-96), late Edo period[に-25]

This volume of Honzo zufu was formerly a possession of the Tayasu Family. Honzo zufu was distributed by subscription. The first four books of the collection (meaning vols. 5-8, since vols. 1-4 are not published) were published by woodblock printing (except that the vols. 5-8 included in this digital exhibition are manuscripts made later). Possibly due to the difficulty in getting funds, volumes 9 to 96 thereafter were published as hand-copied and hand-colored books after a five-year interval. For multi-colored illustration books such as these, if making only a small number of copies, it would have been much simpler and more cost-effective to copy them by hand than to make wood blocks for printing. Consequently, there could be some differences in the quality of each copy, but this particular sample is the copy distributed to the Tayasu Family and is therefore carefully finished.

Traditional Pharmacognosy Collection of the National Diet Library

Traditional Pharmacognosy Collection of the National Diet Library

The National Diet Library holds one of the greatest collections of traditional pharmacognosy. The Ito Collection consists of approximately 2,000 traditional pharmacognosy-related books that were collected by Ito Keisuke, and organized and preserved by his grandson, Tokutaro. The collection includes precious reference materials such as Shokubutsu zusetsu zassan![]() which contains autographic articles of many naturalists, originals and copies of scattered books, single-prints, letters and related advertisements. Moreover, the Shirai Collection consists of approximately 6,000 volumes of traditional pharmacognosy-related old books from Japan, China and the West, which were old possessions of Shirai Mitsutaro. It includes most of the reference materials used in his best-known literary work titled Nihon hakubutsugaku nempyo

which contains autographic articles of many naturalists, originals and copies of scattered books, single-prints, letters and related advertisements. Moreover, the Shirai Collection consists of approximately 6,000 volumes of traditional pharmacognosy-related old books from Japan, China and the West, which were old possessions of Shirai Mitsutaro. It includes most of the reference materials used in his best-known literary work titled Nihon hakubutsugaku nempyo![]() . In addition, 89 pieces of Ono Ranzan-related articles were contributed to the library by his descendants in 2001

. In addition, 89 pieces of Ono Ranzan-related articles were contributed to the library by his descendants in 2001![]() . This collection includes Honzo komoku soko exhibited in this digital exhibition, as well as Ranzan-o gazo (lit. Portrait of Ono Ranzan)

. This collection includes Honzo komoku soko exhibited in this digital exhibition, as well as Ranzan-o gazo (lit. Portrait of Ono Ranzan) ![]() painted by TANI Buncho. These two items and nine other items were designated as Important Cultural Properties in 2015.

painted by TANI Buncho. These two items and nine other items were designated as Important Cultural Properties in 2015.

Materials related to traditional pharmacognosy continued to grow gradually after the addition of these major contributions. The letter of Sugita Gempaku introduced in the exhibition is a donative from the Kinoshita Family, the addressee of the letter. The descendants of HASEGAWA Hitoshi the entomologist, have donated Shirai Mitsutaro ate hagaki (postcards addressed to Shirai Mitsutaro) sent from Minakata Kumagusu. Moreover, the official duty records of Tamura Ransui and his son Yoshiyuki titled Mannencho![]() have joined the collection, thanks to the contribution from their descendants. These are wonderful examples of our collections attracting more materials, enriching the collection even more.

Furthermore, more detailed descriptions of the traditional pharmacognosy collection can be viewed at another digital exhibition titled “Fauna and Flora in Illustration: Natural History of the Edo period (Japanese)

have joined the collection, thanks to the contribution from their descendants. These are wonderful examples of our collections attracting more materials, enriching the collection even more.

Furthermore, more detailed descriptions of the traditional pharmacognosy collection can be viewed at another digital exhibition titled “Fauna and Flora in Illustration: Natural History of the Edo period (Japanese)![]() ”.

”.

SUGITA Gempaku, 1733-1817

An official doctor for the Obama Domain. Gempaku translated and published Kaitai shinsho, the first professional translated text on Western medicine, together with Maeno Ryotaku, Nakagawa Jun’an and Katsuragawa Hoshu in 1774. The book had a tremendous impact on the development of Japanese medicine. In the memoirs Rangaku kotohajime, which he published later in life, Gempaku described the hardship he experienced during the translation process. Gempaku also contributed in the development of Dutch studies, raising students such as Otsuki Gentaku at his homeschool.

An official doctor for the Obama Domain. Gempaku translated and published Kaitai shinsho, the first professional translated text on Western medicine, together with Maeno Ryotaku, Nakagawa Jun’an and Katsuragawa Hoshu in 1774. The book had a tremendous impact on the development of Japanese medicine. In the memoirs Rangaku kotohajime, which he published later in life, Gempaku described the hardship he experienced during the translation process. Gempaku also contributed in the development of Dutch studies, raising students such as Otsuki Gentaku at his homeschool.

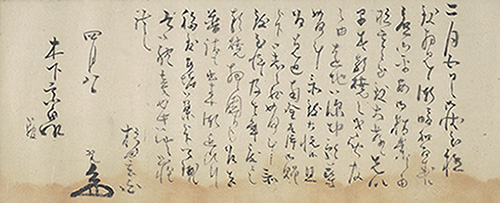

27 Sugita Gempaku shokan (from Kinoshita monjo), [1806][YR1-N23]

A letter written by Gempaku and addressed to Kinoshita Sohaku. Sohaku was also an official doctor for the Obama Domain, who studied under Gempaku. The contents of the letter consist of a reply to the letter from Sohaku and a thank-you note for the expression of sympathy after a fire. It is assumed that Gempaku had written this in 1806, at the age of 74. Kinoshita monjo, to which this letter belongs, is a compilation of letters from the Sugita Family and other documents organized in 1909 by Kinoshita Hiromu, who was a doctor and a descendant of Sohaku. Tomioka Tessai, a famous Japanese-style painter who had close relations with the Kinoshita, had scribed the note of authentication on the box and the preface for them.

KATSURAGAWA Hoshu, 1751-1809

An in-house doctor for the Shogunate, had taken a part in the translation of Kaitai shinsho, the first professional translated text on Western medicine. When the chief of the Dutch factory, Carl Peter Thunberg, had paid a visit to the Edo court, Hoshu had talks with him in an effort to absorb new knowledge. Hoshu had interviewed Daikokuya Kodayu about his experience and observation in Russia, and categorized and recorded them by order of the Shogun Tokugawa Ienari. The record titled Hokusa bunryaku became recognized as one of the greatest literary works.

An in-house doctor for the Shogunate, had taken a part in the translation of Kaitai shinsho, the first professional translated text on Western medicine. When the chief of the Dutch factory, Carl Peter Thunberg, had paid a visit to the Edo court, Hoshu had talks with him in an effort to absorb new knowledge. Hoshu had interviewed Daikokuya Kodayu about his experience and observation in Russia, and categorized and recorded them by order of the Shogun Tokugawa Ienari. The record titled Hokusa bunryaku became recognized as one of the greatest literary works.

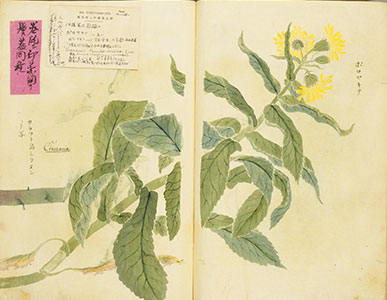

28 KOBAYASHI Toyoaki (Painter), Ezo somokuzu, transcribed by KATSURAGAWA Hoshu, 1793[寄別11-2]

An illustrated catalog of the flora in the western part of Ezochi (The Sea of Japan coastline of Hokkaido) and the southern part of Karafuto (Sakhalin) compiled by Kobayashi Toyoaki, a Shogunate official who explored the area in 1792 and made sketches of vegetation he witnessed and categorized them. The inserted material is a replica Hoshu had made in 1793 from the copy of the book that was presented to the Shogunate. The part depicted is poroyakina, or senecio pseudoarnica. The piece was formerly owned by Ito Keisuke, and his handwriting can be seen on the pink label attached. There is also a memo written by Ito Tokutaro, who was the grandson of Keisuke and a Doctor of Science. Moreover, the person who wrote down the botanical name “Cineraria” on this article is considered to be Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold himself.

KURIMOTO Tanshu, 1756-1834

The second son of Tamura Ransui, was later adopted by the Kurimoto Family, which was the family of the Shogunate physicians. Tanshu gave lectures on the traditional pharmacognosy and appraised medicines at the Shogunate Medical School as an official in-house doctor. Tanshu strove for the enhancement of zoological studies that were then thought little of, and left literary works including titles such as Kowa gyofu (lit. Encyclopedia of Fishes in Japan)

The second son of Tamura Ransui, was later adopted by the Kurimoto Family, which was the family of the Shogunate physicians. Tanshu gave lectures on the traditional pharmacognosy and appraised medicines at the Shogunate Medical School as an official in-house doctor. Tanshu strove for the enhancement of zoological studies that were then thought little of, and left literary works including titles such as Kowa gyofu (lit. Encyclopedia of Fishes in Japan) ![]() and Senchu-fu (lit. Thousand Insects picture book)

and Senchu-fu (lit. Thousand Insects picture book)![]() . He is also known for giving Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold copies of Kaikarui shashin (lit. Illustrations of Crustacean Species) and Gyorui shashin (lit. Illustrations of Fish Species), both of which were quoted by Siebold in his editorial work titled Fauna Japonica.

. He is also known for giving Philipp Franz Balthasar von Siebold copies of Kaikarui shashin (lit. Illustrations of Crustacean Species) and Gyorui shashin (lit. Illustrations of Fish Species), both of which were quoted by Siebold in his editorial work titled Fauna Japonica.

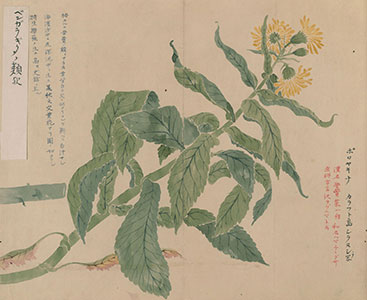

29 KOBAYASHI Toyoaki (Painter), Ezo somokuzu, transcribed by KURIMOTO Tanshu, 1797[亥-215]

In 1797, Hotta Masaatsu, who was a wakadoshiyori (junior councilor of the Shogunate), ordered Tanshu to add notations in both Chinese and Japanese along with explanatory notes to the copy of Ezo somokuzu in his private collection. The inserted material is a transcribed copy Tanshu had made for his own use on that occasion. Insertions written in vermillion ink were of Tanshu, whereas memos in indigo ink were written by another Shogunate doctor by the name of Saka Tankyu. Though publication utilizing woodcut prints was getting popular in the Edo period, copies-by-hand continued to be in circulation. Both Materials 28 and 29 are carefully duplicated and have a high resemblance to their original. However, the differences in the original copies the duplications were made from, and insertions made by each owner, have made the contents of the two already different from each other. ![]()