Chapter 2: Regarding literary works Gesaku writers

Gesaku writers

SANTO Kyoden, 1761-1816

Kyoden is a novelist from the late Edo period. Receiving praise from Ota Nampo, Kyoden became a very popular writer. Other than authoring various genres of literature, his achievement includes studies on antique utensils. He was also known as an ukiyo-e artist.

Kyoden is a novelist from the late Edo period. Receiving praise from Ota Nampo, Kyoden became a very popular writer. Other than authoring various genres of literature, his achievement includes studies on antique utensils. He was also known as an ukiyo-e artist.

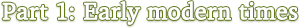

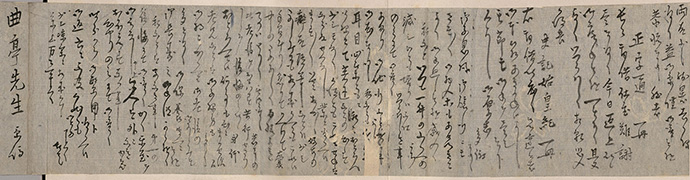

18 Santo Kyoden eiri shokan, April 6, [ca. 1813][WA47-13]

A letter sent from Kyoden to Sugawara Tosai, who was an artist and a connoisseur. Kyoden asks to make a replica of an ancient painting of “Mushi no tareginu (lit. Insect silk curtain, curtain that was hung around a woven hat)”, and inquires about the woven hats depicted in old picture scrolls. There is an article regarding a monograph on antique utensils by Kyoden titled Kottoshu, which suggests that the letter was written when Kyoden was collecting materials for the book.

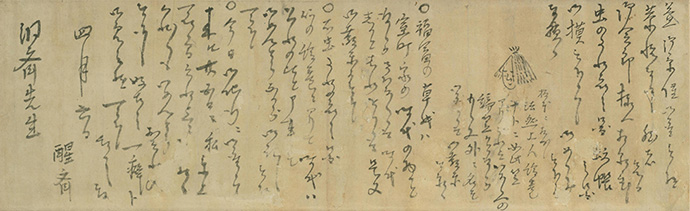

18 Related material: SANTO Kyoden, Kottoshu (copy), TSURUYA Kiemon, 1815[841-11]

Inserted part shows that dealt with “Mushi no tareginu kozu”, which is included in Book 2 of the Kottoshu volume 1. Printed examples from various literatures are gathered together.

19 Santo Kyoden shokan (from Kyokutei raikanshu), [ca. July to August, 1815][WA25-21]

A letter sent from Kyoden to another novelist, Kyokutei Bakin. He wrote that writing novels was something he must do but was seldom interested, whereas studying antique utensils was fun but took time and effort. He also went on to complain how he regreted the way he spent his younger days without experiencing any hardship, and nowadays his body was getting too weak to move as he wished it to. It provides an interesting insight into the feelings of the popular novelist that Kyoden had become.

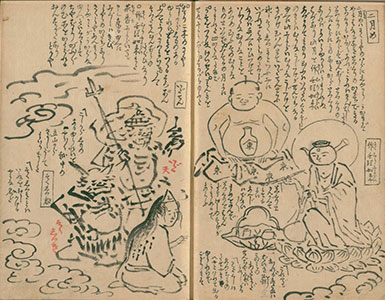

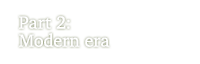

19 Related material: Sakusha tainai totsuki no zu (Kyoden's own handwriting), [1804][WA19-9]

An illustration of the stages of suffering for not having any ideas for writing kibyoshi, or an illustrated storybook, using a metaphor of ten months of pregnancy. This particular piece depicts the second month. The teapot-faced guardian deity on the right side is named Sakumuri (slump) Buddha, which is a parody of Shakamuni Buddha (Gautama Siddhartha). The teapot-face comes from his tendency to drink too much tea when having a hard time putting together the plot. ![]()

RYUTEI Tanehiko, 1783-1842

A novelist from the late Edo period, whose family had been direct vassals of the Shogunate. Tanehiko’s talent flourished in the genre of novel known as gokan. His work titled Nise murasaki inaka genji (lit. Bogus Murasaki, Bumpkin Genji) became especially popular, but was banned from publication.

A novelist from the late Edo period, whose family had been direct vassals of the Shogunate. Tanehiko’s talent flourished in the genre of novel known as gokan. His work titled Nise murasaki inaka genji (lit. Bogus Murasaki, Bumpkin Genji) became especially popular, but was banned from publication.

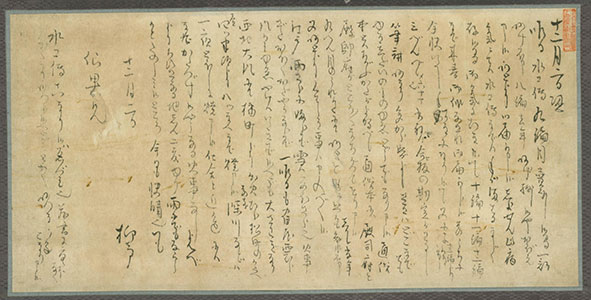

20 Ryutei Tanehiko shojo, December 2, [1830][WA25-93]

This letter was sent from Tanehiko, addressed to one of his apprentices named Ryutei Senka. In the letter, Tanehiko asks Senka to write for him parts 10 through 12 of Kanagaki suikoden. He also says that he intends to write part 13 himself, he prefers to have fewer people to make clean copies, and other related matters. Although Tanehiko did write part 13, from part 14 and on were again written by Senka and others.

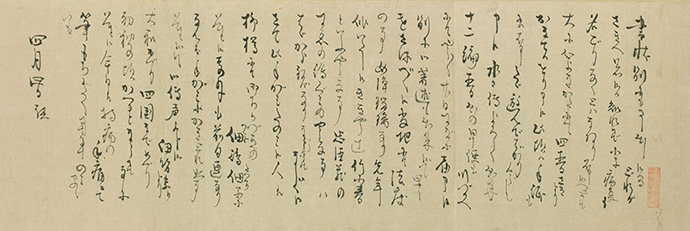

21 Ryutei Tanehiko jihitsu shokan, April 4, [1831][WA25-86]

Six months after the Materials 20 was sent, Tanehiko again wrote and sent this letter to Senka. Tanehiko wrote about his illness and the arrival of Kanagaki suikoden part 12, which Senka had written for Tanehiko. The latter half of the letter is spent on the introduction of the person Tanehiko had asked to deliver this letter.

21 Related material: RYUTEI Tanehiko, UTAGAWA Kuniyoshi (painter), Kanagaki suikoden (copy), NISHIMURAYA Yohachi, 1830, Repository: Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library (特別文庫 特649)

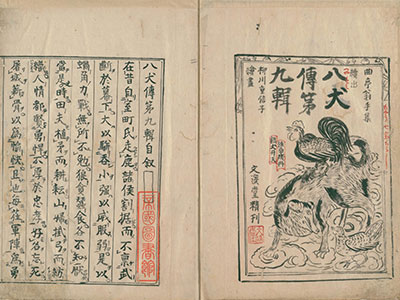

The book that appeared in the preceding letter. It is the abridged translation of a Chinese novel from the Ming dynasty titled Chugi suikoden, making it easier for the public to comprehend. Since the National Diet Library does not own a copy, the photograph shown is provided by the Tokyo Metropolitan Central Library and is taken from Book 2 of Part 8.

KYOKUTEI Bakin, 1767-1848

TAKIZAWA Michi, 1806-1858

A novelist from the late Edo period. His representative works include Chinsetsu yumiharizuki and Nanso satomi hakkenden. Bakin started to lose his sight from 1834, and was nearly blind by 1840. Thereafter, Michi, the widow of Bakin’s deceased first son, had helped him by taking dictations for his manuscripts and letters.

A novelist from the late Edo period. His representative works include Chinsetsu yumiharizuki and Nanso satomi hakkenden. Bakin started to lose his sight from 1834, and was nearly blind by 1840. Thereafter, Michi, the widow of Bakin’s deceased first son, had helped him by taking dictations for his manuscripts and letters.

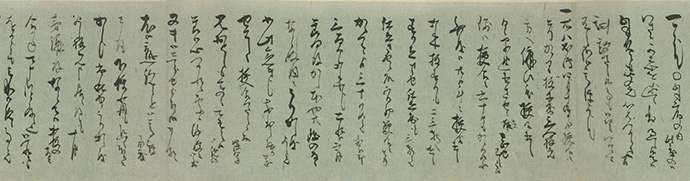

22-1 Kyokutei Bakin shokan (Bakin’s own handwriting)(from Kyokutei Bakin shokan), May 21, [1832][WA25-27]

A letter written by and sent from Bakin to his friend and admirer, Tonomura Josai. It continues for about 300 lines. Bakin writes about books which he borrowed as well as works of Bakin among other topics. Other topics Bakin describes include how 260 out of 300 copies of his new book, Nanso satomi hakkenden were sold on the first day alone, and how he was able to check the print against his manuscript in about 20 days, which usually takes about 60 days.

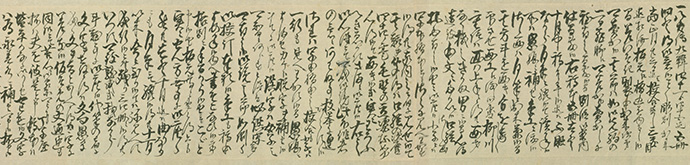

22-2 Kyokutei Bakin shokan (TAKIZAWA Michi wrote for Bakin, Bakin wrote the additional notes)(from Kyokutei Bakin shokan), January 28, [1841][WA25-27]

This letter is another long letter sent from Bakin to Tonomura Josai, which contains about 450 lines. Though Michi wrote the main text for him, Bakin wrote the additional notes put at the beginning himself. The letter contains a New Year’s greeting and some thoughts on his own work among other topics. Bakin also mentions his experience of having Michi take dictation for him when he was writing Nanso satomi hakkenden, criticizing to her that “if I concentrate on teaching her how to write each character, sentences get ignored, and if I focus on sentences, she cannot write characters”. In the part Bakin wrote with his own hand, he comments on Michi’s writing, saying that “there will be many misspellings and some parts cannot be read”. ![]()

22 Related material: Nanso satomi hakkenden(Bakin’s own handwriting), Vol. 9, [1834][WA19-15]

This draft is in Bakin’s own handwriting. This is when he was still able to write on his own. ![]()