Chapter 3 Diaries The Great Kanto Earthquake

The Great Kanto Earthquake

On September 1, 1923, an earthquake of unprecedented strength struck the southern Kanto region with a seismic intensity of Shindo 7. Here is how two different people recorded the events of that day in their diaries.

NAGATA Hidejiro, 1876-1943

Nagata was a government bureaucrat and politician during the Taisho and Showa eras. After terms as governor of Mie Prefecture and a member of the House of Peers, he served as mayor of the City of Tokyo and diligently worked to help the city recover from the Great Kanto Earthquake. He later served as both Minister of Overseas Affairs and Minister of Railways. He was a noted poet of haiku, who had been familiar with this 5-7-5 syllable form of poetry since his youth and published works under the pen name Seiran. A talented speaker, he often appeared on radio during the early days of that medium.

Nagata was a government bureaucrat and politician during the Taisho and Showa eras. After terms as governor of Mie Prefecture and a member of the House of Peers, he served as mayor of the City of Tokyo and diligently worked to help the city recover from the Great Kanto Earthquake. He later served as both Minister of Overseas Affairs and Minister of Railways. He was a noted poet of haiku, who had been familiar with this 5-7-5 syllable form of poetry since his youth and published works under the pen name Seiran. A talented speaker, he often appeared on radio during the early days of that medium.

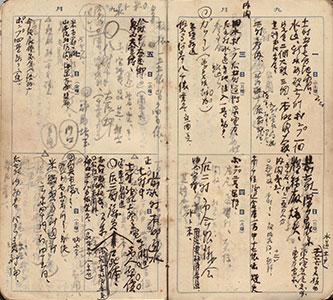

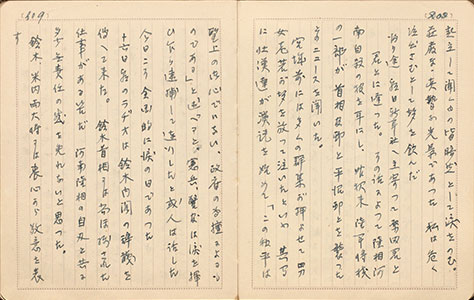

122 Nagata Hidejiro techo, September 1, 1923[Nagata Hidejiro, Ryoichi Papers: 1430]

This is a pocket notebook used by Nagata while he served as mayor of the City of Tokyo at the time of the Great Kanto Earthquake. The pages contain only matter-of-fact descriptions of the damage to the water system, reservoirs, and other parts of the infrastructure, vividly demonstrating his tense feeling as a person concerned.

SAITO Makoto, 1858-1936

Saito was a naval officer and politician, who lived during the Meiji, Taisho, and Showa eras, and served as Japan’s 30th Prime Minister. A Naval Academy graduate, he served as Minister of the Navy on five consecutive cabinets, was Admiral and Governor-General of Korea, and was appointed Prime Minister in 1932 after an attempted coup d’état by right-wing elements, known as the May 15 Incident. As Prime Minister, he oversaw the organization of a national unity cabinet, the creation of Manchukuo, and Japan’s withdrawal from the League of Nations. Later, a bribery scandal related to the Teijin Silk Company and known as the Teijin Incident led to the resignation of the Cabinet in 1934. He was later named Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal and assassinated during the February 26 Incident in 1936.

Saito was a naval officer and politician, who lived during the Meiji, Taisho, and Showa eras, and served as Japan’s 30th Prime Minister. A Naval Academy graduate, he served as Minister of the Navy on five consecutive cabinets, was Admiral and Governor-General of Korea, and was appointed Prime Minister in 1932 after an attempted coup d’état by right-wing elements, known as the May 15 Incident. As Prime Minister, he oversaw the organization of a national unity cabinet, the creation of Manchukuo, and Japan’s withdrawal from the League of Nations. Later, a bribery scandal related to the Teijin Silk Company and known as the Teijin Incident led to the resignation of the Cabinet in 1934. He was later named Lord Keeper of the Privy Seal and assassinated during the February 26 Incident in 1936.

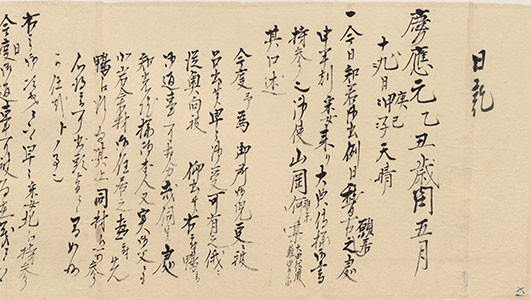

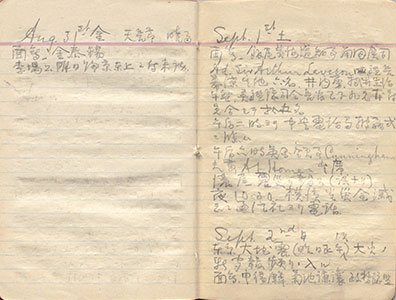

123 Saito Makoto techo, September 1, 1923[Saito Makoto Papers, Documents: 208-65]

This pocket notebook was used by Saito during his term as Governor-General of Korea at the time of the Great Kanto Earthquake. His entry for September 1 states that he received a report of an earthquake in the Nobi Region, which later proved to be false. Also, that at 10:30 p.m., a news service agency called and informed him that Yokohama had been “completely destroyed” by fire. Despite its brevity, his entry clearly shows how only conflicting information was available due to the great distance from the scene of the earthquake and how the staff of the Government-General of Korea attempted to gather information.

Chapter 3 Diaries The day after the war ended

The day after the war ended

August 16, 1945, the day after the Imperial Rescript on the Termination of the War was broadcast on the radio, is the day Japanese people took their first steps into the postwar period. Here are the entries for that day from the diaries of three different people.

ARIMA Yoriyasu, 1884-1957

Arima was a politician during the Taisho and Showa eras, who held the title of count as the heir of the former lord of the Kurume Domain, Arima Yoritsumu. After graduating from the Agriculture College of the Imperial University of Tokyo and serving as an assistant-professor there, he was elected to the House of Representatives in 1924 and was a supporter of the Zenkokusuiheisha (National Levelers Association) and the movement to unionize farmworkers. He was appointed to the post of Minister of Agriculture in the first Konoe Cabinet. After serving as the first Secretary General of the Taisei Yokusankai (the Imperial Rule Assistance Association) for nearly six months, he retired from politics and became President of Teikoku Suisan Tosei KK (the Imperial Fish Products Holding Co.) which was established as a central coordinating organization for the cold storage and sales of marine products. After the war, he became President of the Japan Racing Association and contributed to development of horse racing. The Arima Kinen (the Arima Memorial) was named in his memory.

Arima was a politician during the Taisho and Showa eras, who held the title of count as the heir of the former lord of the Kurume Domain, Arima Yoritsumu. After graduating from the Agriculture College of the Imperial University of Tokyo and serving as an assistant-professor there, he was elected to the House of Representatives in 1924 and was a supporter of the Zenkokusuiheisha (National Levelers Association) and the movement to unionize farmworkers. He was appointed to the post of Minister of Agriculture in the first Konoe Cabinet. After serving as the first Secretary General of the Taisei Yokusankai (the Imperial Rule Assistance Association) for nearly six months, he retired from politics and became President of Teikoku Suisan Tosei KK (the Imperial Fish Products Holding Co.) which was established as a central coordinating organization for the cold storage and sales of marine products. After the war, he became President of the Japan Racing Association and contributed to development of horse racing. The Arima Kinen (the Arima Memorial) was named in his memory.

124 Arima Yoriyasu nikki, August 16, 1945[Arima Yoriyasu Papers (No.1): 98-12]

Arima was president of Teikoku Suisan Tosei KK (the Imperial Fish Products Holding Co.) at the end of the war. His entry includes pragmatic descriptions for the day’s events, such as a meeting held at 9 a.m. that day at the Fisheries Office of people involved in the wartime regulation of the fishing industry to discuss the near future, immediate increases in production, and other proposals for the postwar fishing industry.

ASHIDA Hitoshi, 1887-1959

Ashida was a diplomat and politician as well as Japan’s 47th Prime Minister. After graduating from the Imperial University of Tokyo, he served in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In 1932, he left the Ministry to seek election to the House of Representatives and thereafter served 11 terms as a member of that organ. After the war, he served as Chairman of the Committee on the Bill for Revision of the Imperial Constitution in the House of Representatives. He helped found the Minshu-to (Democratic Party) and became its president in 1947, serving as both Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs in coalition cabinet the following year. He resigned six months later, however, in the aftermath of a bribery scandal involving the president of Showa Denko K.K. After joining the Kaishin-to (Japan Reform Party), he later moved to the Liberal Democratic Party.

Ashida was a diplomat and politician as well as Japan’s 47th Prime Minister. After graduating from the Imperial University of Tokyo, he served in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. In 1932, he left the Ministry to seek election to the House of Representatives and thereafter served 11 terms as a member of that organ. After the war, he served as Chairman of the Committee on the Bill for Revision of the Imperial Constitution in the House of Representatives. He helped found the Minshu-to (Democratic Party) and became its president in 1947, serving as both Prime Minister and Minister of Foreign Affairs in coalition cabinet the following year. He resigned six months later, however, in the aftermath of a bribery scandal involving the president of Showa Denko K.K. After joining the Kaishin-to (Japan Reform Party), he later moved to the Liberal Democratic Party.

125 Ashida Hitoshi nikki, (August 16, 1945)[Ashida Hitoshi Papers, Documents: 1]

Ashida was a member of the House of Representatives at the end of the war. His diary contains only a brief description for the day in question, stating that he could not shake the feeling that the mass resignation of the Suzuki Cabinet and the suicide of Minister of War Anami Korechika smacked of irresponsibility. Ashida was known as a diplomatic expert for the Rikken Seiyukai (the Friends of Constitutional Government Party), but was ostracized because of his critical attitude toward the military and the Taisei Yokusankai (the Imperial Rule Assistance Association).

Chapter 3 Diaries Diary collection

Diary collection

IWAKURA Tomomi

: See Materials 41.

126 Iwakura Tomomi nikki, May 18-25, 1865[Kawakami Naonosuke Papers: 12]

This is a fragment from a diary written on rolled letter paper by Iwakura Tomomi. Iwakura was an aristocrat who keenly promoted the marriage of the Komei Emperor’s sister, Princess Kazunomiya, to the Tokugawa family, but lost his standing in the imperial court when he fell under suspicion of conspiring with the Shogunate. He was expelled from central Kyoto and was placed under house arrest in Iwakura, a northern suburb of Kyoto in 1862, where he remained for five years. The inserted material contains a description from the intercalary fifth month of 1865, during the time of his house arrest. It contains an account of his third son, Chikamaru (later Iwakura Tomosada), who had resigned his position as a page at the imperial court due to his father’s situation, but who was recalled to his post at the Emperor’s personal insistence.

HAMAGUCHI Osachi 1870-1931

Hamaguchi was a politician and Japan’s 27th prime minister. After serving as the Minister of Finance, Hamaguchi joined the Rikken Doshikai (Constitutional Association of Friends) and became a member of the House of Representatives. Successively assuming the posts of Minister of Finance and Minister of the Interior, Hamaguchi was president of the Rikken Minsei-to (Constitutional Democratic Party) when he became Prime Minister in 1929. His achievements included achieving financial austerity, a gold embargo, and conclusion of the London Naval Treaty. He was seriously wounded at Tokyo Railway Station by a right-wing fanatic in 1930, and although he survived, he died less than a year later.

Hamaguchi was a politician and Japan’s 27th prime minister. After serving as the Minister of Finance, Hamaguchi joined the Rikken Doshikai (Constitutional Association of Friends) and became a member of the House of Representatives. Successively assuming the posts of Minister of Finance and Minister of the Interior, Hamaguchi was president of the Rikken Minsei-to (Constitutional Democratic Party) when he became Prime Minister in 1929. His achievements included achieving financial austerity, a gold embargo, and conclusion of the London Naval Treaty. He was seriously wounded at Tokyo Railway Station by a right-wing fanatic in 1930, and although he survived, he died less than a year later.

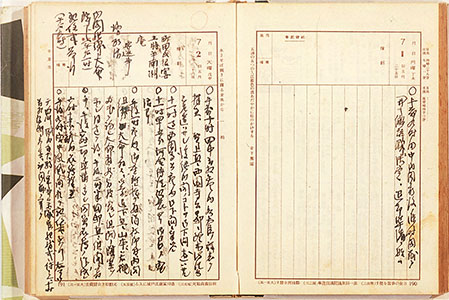

127 Hamaguchi Osachi nikki, July 2, 1929[Hamaguchi Osachi Papers: 2]

Hamaguchi wrote in a daily journal sold by Hakubunkan, the format of which includes a page for each day and is characteristically divided into sections for the weather, temperature, and the day’s events. The entry for July 2, 1929, contains comments on the mass resignation of Tanaka Cabinet and Hamaguchi’s own appointment as Prime Minister by imperial command.

The first commercial diaries

The first printed diaries to be produced in Japan were called kaichu nikki (pocket diary) and came from the Ministry of Finance Printing Bureau in 1880.

In 1895, Hakubunkan published a pocket diary for 1896 that was printed on better-quality paper than used by the Printing Bureau and even came with a pencil attached. The following year, Hakubunkan established itself as Japan’s leading publisher of diaries by releasing the first toyo nikki (daily journal). Hamaguchi Osachi used the toyo nikki to keep his journal.

*Page showing New Year’s Day from a 1888 toyo nikki, published by Ministry of Finance Printing Bureau, September, 1887[特71-905]![]()

ABE Katsuo, 1891-1948

Abe was a naval officer during the Showa era, who commanded several warships and rose to the rank of vice admiral. During World War II, he promoted the conclusion of the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy, often residing in Germany as Japan's representative to the joint technical commissions of the Tripartite Pact.

Abe was a naval officer during the Showa era, who commanded several warships and rose to the rank of vice admiral. During World War II, he promoted the conclusion of the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy, often residing in Germany as Japan's representative to the joint technical commissions of the Tripartite Pact.

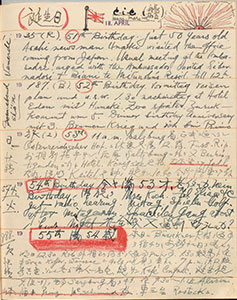

128 Abe Katsuo nikki, 1941-1945[Modern Japanese Political History Materials Room Collection: 1371-2]

Abe used a ren’yo nikki (a multiple-year diary), which allows a person to write about the same day of various years on a single page. The inserted material includes a five-year diary, which he inscribed with a vermilion-colored pencil on his birthday, April 18. The meticulous entries reveal an unexpected side of this elite naval officer. In the entry for September 27, 1941, his comments celebrate the 1st anniversary since the conclusion of the Tripartite Pact with Germany and Italy, while four years later, in 1945, he records his mixed feelings regarding the Emperor Showa’s visit to Douglas MacArthur, saying, “Ah, that can I possibly say”.

When did horizontal writing come into use?

Although the Japanese language was originally written from top to bottom, it is now commonly written and read from left to right. Prior to WWII, however, it was not uncommon to see Japanese script that was read from right to left.

The use of right-to-left or left-to-right script in Japan began during the late Edo period, when the Roman alphabet was introduced via the Netherlands. As it began to appear in ukiyo-e and other places, there were many who did not know in which direction to read it. To solve this problem, right-to-left script was officially adopted during the Meiji era for script on train tickets, bank notes, and other printed materials to match the direction in which top-to-bottom script was read. The use of left-to-right script was limited only to those engaged in the study of mathematics or other academic subjects.

Thereafter, right-to-left script and left-to-right script were often combined, and it was not until some time after WWII that right-to-left was officially declared obsolete.

The horizontal script in this digital exhibition include examples by Yoshio Joen, Udagawa Genzui, and Nishimura Shigeki in the section "Eye of science, struggle with Western language" and in diaries kept by Saito Makoto and Abe Katsuo written in both Japanese and English in the section "Diaries".