Chapter 8 Writers (1)

SAN'YUTEI Encho, 1839-1900

Encho was a rakugo storyteller. He took the name Koenta and gave his first Japanese vaudeville performance when he was 7 years old. Later, he changed his name to Encho and became popular with stories about human nature or emotions and ghost stories. He is called the founder of modern rakugo. He was also enthusiastic about creating rakugo stories and wrote new rakugos including his representative works, Shinkei Kasanegafuchi, Kaidan botan doro which are still performed today. Kaidan botan doro which was published with the purpose of disseminating stenography had great influence to establishing gembun icchitai (unification of the spoken and written language).

Encho was a rakugo storyteller. He took the name Koenta and gave his first Japanese vaudeville performance when he was 7 years old. Later, he changed his name to Encho and became popular with stories about human nature or emotions and ghost stories. He is called the founder of modern rakugo. He was also enthusiastic about creating rakugo stories and wrote new rakugos including his representative works, Shinkei Kasanegafuchi, Kaidan botan doro which are still performed today. Kaidan botan doro which was published with the purpose of disseminating stenography had great influence to establishing gembun icchitai (unification of the spoken and written language).

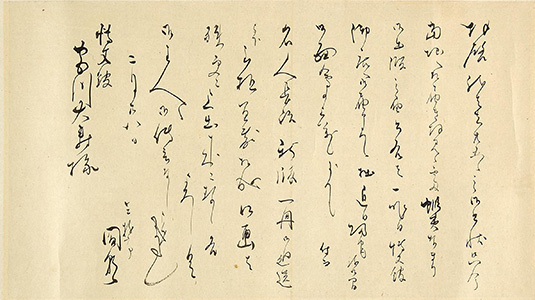

84 San’yutei Encho shokan, February 28, [ca. 1896][Yanagihara Sakimitsu Papers: 2-8]

This is a letter written by Encho to a person at Hakubunkan, a publishing company. In the letter, Encho informs the person that he has sent the application for publishing Chinsetsu ezo namari, and the frontispiece for Meijin Choji, which was readdressed to him, was well drawn. Encho published both Chinsetsu ezo namari and Meijin Choji in March 1896, and the letter is thought to have been written around that time.

OZAKI Koyo, 1867-1903

Ozaki was a novelist. He established Ken’yusha (literary coterie) when he was in the University of Tokyo Prep School. He left the Imperial University in 1890, and devoted himself to writing. His representative works include Tajo takon (lit. Passions and regrets), Konjiki yasha (The golden demon) and others. He died at the age of 37. As an authority in literary circles in the Meiji era, he taught many pupils including Izumi Kyoka and Tokuda Shusei. He was said to be an accommodating person and well-liked by his friends and pupils.

Ozaki was a novelist. He established Ken’yusha (literary coterie) when he was in the University of Tokyo Prep School. He left the Imperial University in 1890, and devoted himself to writing. His representative works include Tajo takon (lit. Passions and regrets), Konjiki yasha (The golden demon) and others. He died at the age of 37. As an authority in literary circles in the Meiji era, he taught many pupils including Izumi Kyoka and Tokuda Shusei. He was said to be an accommodating person and well-liked by his friends and pupils.

IZUMI Kyoka, 1873-1939

Kyoka was a novelist. He decided to be a novelist after reading Ozaki Koyo’s novels in 1890. The following year, he started living with Koyo as a janitor at the age of 19. It is said that when his father died and he was in financial difficulty, Koyo encouraged him to continue writing. When Koyo died, Kyoka wrote a eulogy, and published reminiscences about by Koyo several times. His representative works include Koya hijiri (The Koya priest), Uta andon (lit. A Song by Lantern-light).

Kyoka was a novelist. He decided to be a novelist after reading Ozaki Koyo’s novels in 1890. The following year, he started living with Koyo as a janitor at the age of 19. It is said that when his father died and he was in financial difficulty, Koyo encouraged him to continue writing. When Koyo died, Kyoka wrote a eulogy, and published reminiscences about by Koyo several times. His representative works include Koya hijiri (The Koya priest), Uta andon (lit. A Song by Lantern-light).

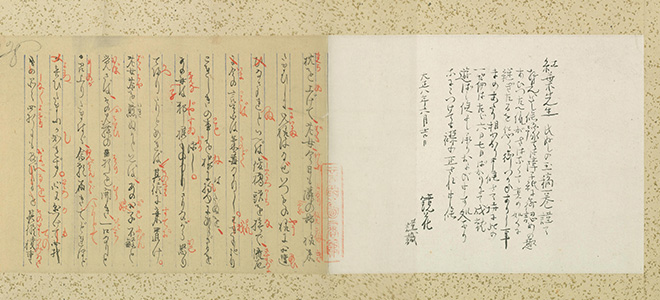

85 Kono nushi, [1890][WA22-2]

This is a part of Koyo’s autograph manuscripts and Kyoka’s shikigo (description of the manuscript or printed book which is placed before or after the text and explains about the copy, how it was obtained, dates concerned, etc.). Kono nushi was published from Shun’yodo in 1890 as the second Shinsaku juniban series. Koyo was still a student at the Imperial University, and the manuscript was written in 7 days before the examination. Years later, Koyo said, “The result of the examination was not very good” (Koyo “Sakka kushindan (No.7)”, 1897).

Kyoka became Koyo’s pupil a year after Kono nushi was written. Shikigo by Kyoka dated in June 1919, which is 16 years after Koyo’s death, shows Kyoka’s yearnings for his master Koyo.

YAMADA Bimyo, 1868-1910

Bimyo was a novelist. He established the Ken’yusha (literary coterie) with Ozaki Koyo and others. He published his representative works including Musashino which was written in colloquial style. He is called a pioneer of novels unifying the spoken and written language along with Futabatei Shimei. Later, he opposed Koyo and left Ken’yusha. He became a hero in the literary world when he was around 20, but was not accepted by the public in his later years. He wrote many fine historical novels.

Bimyo was a novelist. He established the Ken’yusha (literary coterie) with Ozaki Koyo and others. He published his representative works including Musashino which was written in colloquial style. He is called a pioneer of novels unifying the spoken and written language along with Futabatei Shimei. Later, he opposed Koyo and left Ken’yusha. He became a hero in the literary world when he was around 20, but was not accepted by the public in his later years. He wrote many fine historical novels.

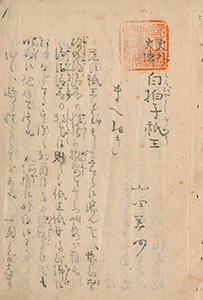

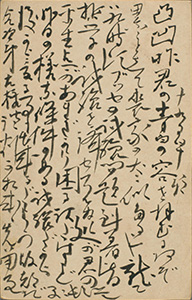

86 Shirabyoshi Gio[本別3-67]

This is an autograph manuscript by Bimyo. It was not published while Bimyo was alive, but was published with the name Gio in 1934. It is not clear when it was written, but is thought to be in his later years. Bimyo wrote several historical novels which featured the Taira Family including Taira no Kiyomori and Taira no Shigehira, and they are highly valued. This Shirabyoshi Gio is also about Kiyomori and Shirabyoshi (a prostitute disguised as a man, which was common in the Heian period) who was loved by Kiyomori, and their surroundings.

MASAOKA Shiki, 1867-1902

Masaoka was a haiku and tanka poet. He had a close communication with Natsume Soseki in the First Higher Middle School. He left the Imperial University and entered the Nihon Shimbun newspaper company. He made the reform movement of haiku poetry and tanka with “Dassai shooku haiwa” and “Utayomi ni atauru sho (lit. A Book Bestowed on Composers of Poems)” serialized in the newspaper Nippon. After suffering from disease for 7 years, he died at the age of 36.

Masaoka was a haiku and tanka poet. He had a close communication with Natsume Soseki in the First Higher Middle School. He left the Imperial University and entered the Nihon Shimbun newspaper company. He made the reform movement of haiku poetry and tanka with “Dassai shooku haiwa” and “Utayomi ni atauru sho (lit. A Book Bestowed on Composers of Poems)” serialized in the newspaper Nippon. After suffering from disease for 7 years, he died at the age of 36.

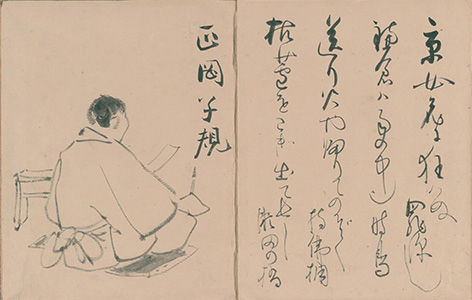

87 Haikai jurokka, 1893[WB12-23]

Representative poems of 16 haiku poets with Shiki as the center with portraits of poets drawn by Shimomura Izan. Shiki chose 4 poems, one for each season, for each haiku poet. Izan is a friend of Shiki who was from Matsuyama, like Shiki. He later achieved great success as an artist for haiga art (haiga art features sketches in light color or India ink with haiku appreciation).

The portrait of Shiki drawn by Izan is shown on the left page, and haiku which was made by 19-year-old Takahama Kyoshi (included in the shown Materials 116) who was a friend of Shiki and written by Shiki is shown on the right page.

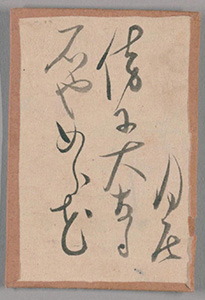

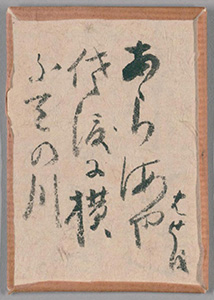

88 Shiki tesei haiku karuta[WB41-55]

Haiku karuta (playing cards) Shiki created with 100 haiku poems written by 100 poets. According to Kawahigashi Hekigoto, Shiki’s friend whose hometown was the same as Shiki’s, it was made around 1894 to 1895. He says Shiki wrote haiku poems on the cards his mother and his younger sister Ritsu made from medicine envelopes (Shiki koji shimpitsu haiku karutacho[158-118-77]). To play, someone reads out a poem and participants compete to be first to find the matching card just like hyakunin isshu karuta. However, haiku does not have kami-no-ku (the first line) and shimo-no-ku (the second line) like waka does, and participants will have to take the card with the words exactly same as the ones the reader reads. This card game may not had been very interesting because Hekigoto says, “It seemed that this card game was rarely played”.

NATSUME Soseki, 1867-1916

Soseki was a novelist. He started communicating with Masaoka Shiki around 1889, and their communication increased as they evaluated each other’s writings. After graduating from the Imperial University, Soseki became an English teacher and went to London to study. After returning to Japan, he published novels while working as an instructor at the Imperial University of Tokyo. He entered the Asahi Shimbun newspaper company in 1907, and published masterpieces including Kojin (The wayfarer) and Kokoro in the newspaper. He is one of the greatest writers in Modern Japanese literature.

Soseki was a novelist. He started communicating with Masaoka Shiki around 1889, and their communication increased as they evaluated each other’s writings. After graduating from the Imperial University, Soseki became an English teacher and went to London to study. After returning to Japan, he published novels while working as an instructor at the Imperial University of Tokyo. He entered the Asahi Shimbun newspaper company in 1907, and published masterpieces including Kojin (The wayfarer) and Kokoro in the newspaper. He is one of the greatest writers in Modern Japanese literature.

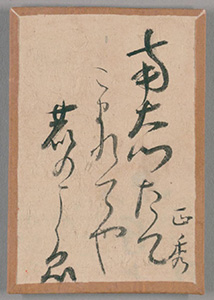

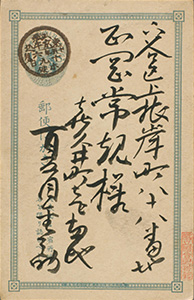

89 Soseki shokan, [1892][本別3-85]

This is a postcard written by Soseki to Masaoka Shiki with the postmark of June 19, 1892. They were both studying at the Imperial University of Tokyo. Soseki mentions a philosophy test they just took, and he is suggesting to Shiki who took the low grade to retake the test. But Shiki did not retake the test and failed the annual test, dropping out of school. In his later years, Shiki looked back on those days in his essay, “Bokuju itteki (A drop of ink)” (1901) and says whenever he started studying for exams, haiku came up in his mind and he could not study for the exam.

SHIMAZAKI Toson, 1872-1943

Shimazaki was a poet and a novelist. He started publishing Bungakukai (lit. The Literary World) with Kitamura Tokoku and others. He started his career as a Romantic poet by publishing a collection of poems, Wakanashu (Collection of young herbs), but after going to the Komoro Gijuku, a private school in Komoro, Nagano Prefecture, he mostly wrote novels. Hakai (The broken commandment) became the first Japanese naturalist novel. His other representative novels include Haru (lit. Spring), Ie (The family), Shinsei (lit. New Life) and Yoakemae (Before the dawn).

Shimazaki was a poet and a novelist. He started publishing Bungakukai (lit. The Literary World) with Kitamura Tokoku and others. He started his career as a Romantic poet by publishing a collection of poems, Wakanashu (Collection of young herbs), but after going to the Komoro Gijuku, a private school in Komoro, Nagano Prefecture, he mostly wrote novels. Hakai (The broken commandment) became the first Japanese naturalist novel. His other representative novels include Haru (lit. Spring), Ie (The family), Shinsei (lit. New Life) and Yoakemae (Before the dawn).

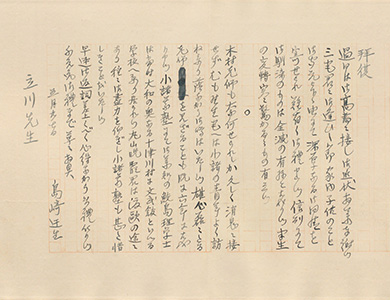

90 Shimazaki Toson shokan, May 27, 1911[Tatsukawa Umpei Papers: 1-7]

This is a letter written by Toson to Tatsukawa Umpei. Tatsukawa was a politician in the Meiji era with a basis in Nagano who pursued democratization. He is said to have been the model for Ichimura in Toson’s Hakai (The broken commandment). In the letter, Toson mentions people at the Komoro Gijuku in Nagano whom they both were friends with and gives their updates. Komoro Gijuku was a private school which was opened by a pastor, Kimura Kumaji, who was Toson’s old teacher. In the letter, Kimura is called “Master Kimura”. Toson was invited to the school by Kimura and taught English and Japanese from 1899. He wrote his representative works including Hakai and Chikumagawa no sukecchi in the 6 years he stayed at the school.