- Kaleidoscope of Books

- WAGASHI

- Part 1: A short history of wagashi

Part 1: A short history of wagashi

Part 1 traces the history of wagashi and describes the confectionery merchants of the Edo period, when wagashi culture blossomed.

A time when the word “kashi” referred to fruit

Although the word kashi means “sweets” in modern Japanese, it originally referred to fruits and nuts. The Japanese–Portuguese dictionary Nippo jisho [869.3-N728], which was published in 1603, says the word “quaxi” (kashi) refers to “fruit, especially after meals.” Today, for example, the word mizugashi (literally, water fruit) can refer either to fruit-based desserts or fresh fruit and harkens back to the days when kashi meant fruit.

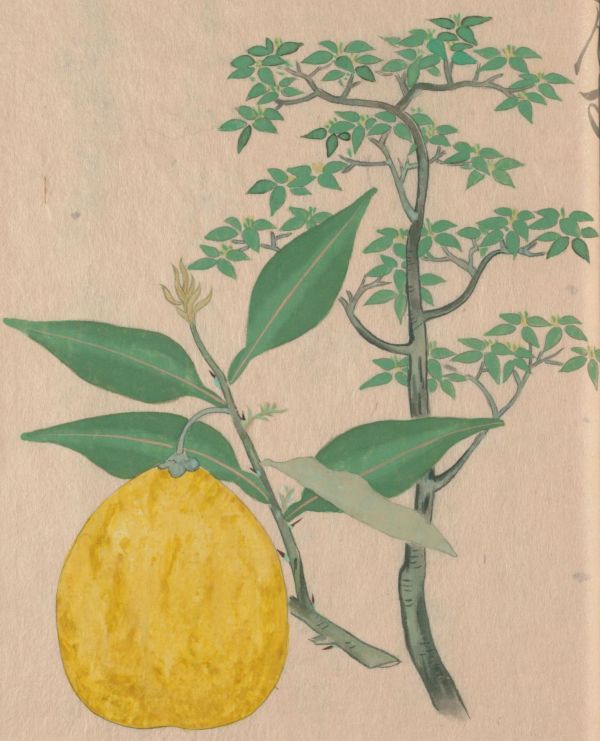

A picture of fruit from Kishubun sanbutsu ezu (Illustrated Dictionary of Products from Kishu).

Fruit is listed as “karui” (confectionery).

Although the word kashi originally referred to fruit, sometime around the 8th century, during the Nara period, kashi began to be used to refer to processed sweets. A major influx of foreign culture from Tang-dynasty China and elsewhere resulted in the introduction of exotic cuisine, such as karakudamono (Tang fruit). These “fruit” were made by adding flavoring and sweetener to rice powder, which was then cooked in frying oil. These confections came in a great many shapes and flavors, and although some are still made today, they are generally used only as offerings.

The emergence of wagashi in the Heian period

The Wakana chapter of Genji monogatari [新別け-2], which is set in the Heian period, includes mention of a food called tsubaimochii, which was served to Imperial courtiers after a game of kemari (a ball game). Kakaisho [本別3-26] is a book of commentary on Genji monogatari that was written during the Muromachi period, and which explains tsubaimochii was made by adding a sweetener called amazura to sticky rice flour and wrapping it with camellia leaf. Although originally a Tang fruit, tsubaimochii was gradually absorbed into Japanese culture, and is one of the earliest examples of wagashi.

The latest foreign culture introduced by Buddhist monks

Wagashi developed rapidly during the Kamakura period and thereafter, often thanks to impetus provided by Buddhist monks who studied in Song-dynasty China and brought back the latest recipes in addition to religious doctrine. To modern Japanese, green tea and wagashi are inseparably associated with each other, but this custom arrived in Japan around this period. Kissaorai [辰-44] is an anthology of letters about tea drinking that was assembled during the 14th century, and which provides one of the earliest descriptions of serving green tea and sweets together.

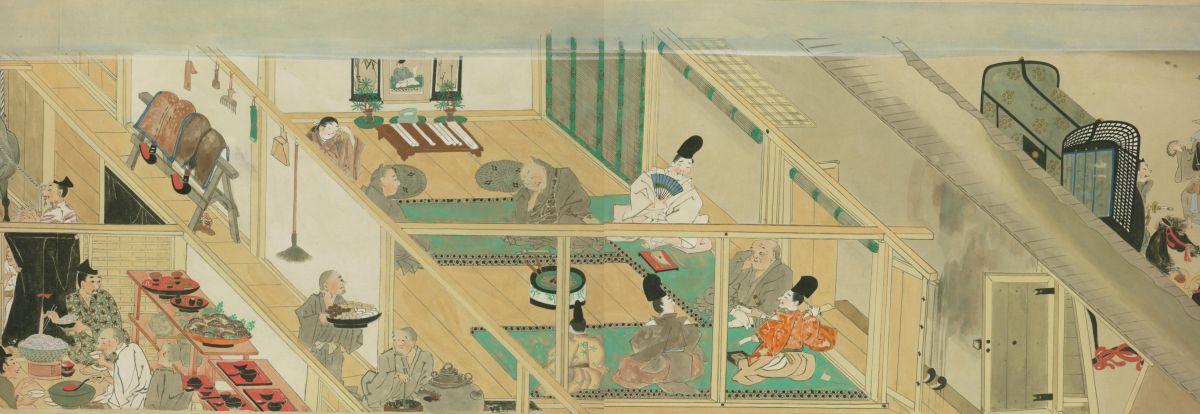

1) Bokie ekotoba by Jishun [ん-169]

This scene depicts a poetry reading held during the Nanbokucho period in the mid-14th century, and is from Bokie ekotoba, which depicted the life of Kakunyo, the third caretaker of Honganji Temple. In the kitchen across the corridor, servants are preparing for the tea ceremony that will be held afterwards. A Buddhist monk is walking along the corridor with a big tray in his hands, which is assumed to be full of confectionery to be served with green tea. Although it is not known exactly what kinds of wagashi were served during tea ceremonies at this time, records from the Sengoku period (16th century) indicate that fruit and knotted kelp were served, among other things.

No discussion of the foods that were introduced by Buddhist monks and led to the development of wagashi can be complete without mentioning tenjin. In China, light meals taken between regular meals were called tenjin, which in modern China is now pronounced dim sum. In Japan, where people took only two meals a day, in the morning and in the evening, tenjin soon came to refer to a light lunch. At the same time, tenjin also refers to the specific types of food that were served. In Teikin'orai written by Gen'e [WA16-69], yokan, udon and manju are described as tenjin. Yokan and manju, of course, are now two of the best known types of wagashi.

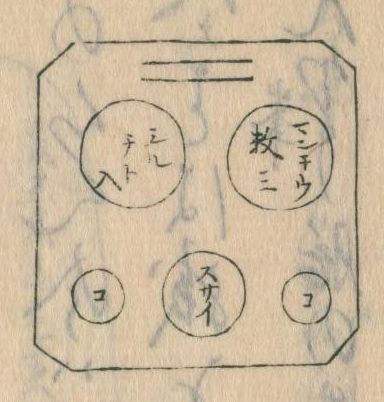

The original style of manju that came to Japan as tenjin was quite different from the present-day wagashi. It was most likely not as sweet and contained no bean jam. There is a schematic diagram in “Sogooozoshi” [127-1], a very detailed manual of table manners and other etiquette from the Muromachi period, that shows the proper placement on a serving tray of chopsticks as well as individual bowls containing three small manju, soup, and pickled vegetables.

This illustration shows the placement on a serving tray of chopsticks as well as individual bowls of three manju, soup, and pickled vegetables.

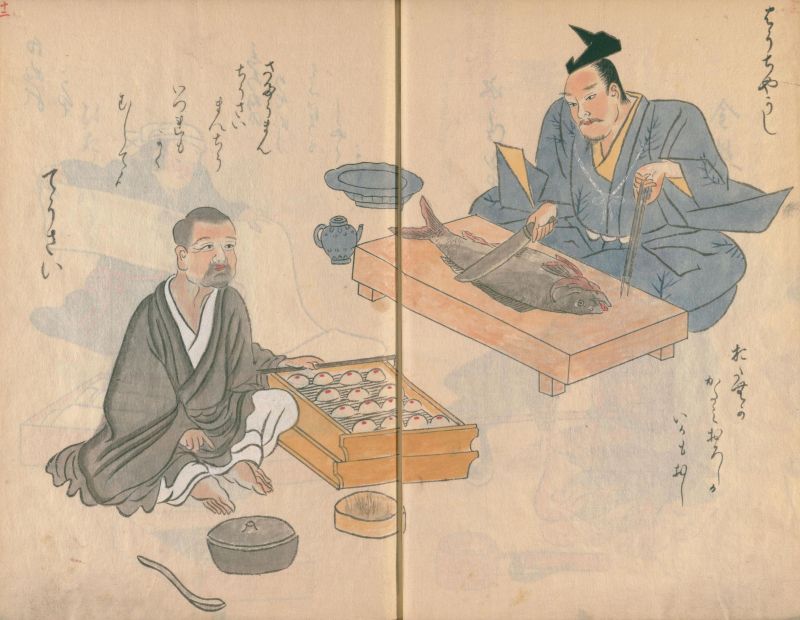

Shokunin utaawase ehon [よ-12] contains an illustration of a manju vendor from the Muromachi period. The text over his head describes his wares as “sugar manju and vegetable manju, well steamed.” Vegetable manju is made by filling a Chinese steamed bun with vegetable jam, and resembles very closely modern dim sum. On the other hand, sugar manju, as the name suggests, is thought to have been a steamed bun made with sugar paste, and is considered one of the original forms of wagashi manju. This is how wagashi gradually developed from what was originally dim sum.

This picture of a manju vendor is thought to be a duplication of the one in Shichijuichiban shokunin utaawase.

Wagashi and the Portuguese

The Portuguese played an essential role in the development of wagashi. During the Age of Discovery, merchants and missionaries from Portugal and other European countries came to Japan to initiate trading and spread the Christian religion. At the same time, they were the first to bring to Japan European confections, such as a type of sponge cake that became known as castella and is still popular in Japan today. One major impact of this was a loosening of the prevailing religious taboo against the eating of chicken eggs. In fact, the only modern exception to the rule that wagashi must be made of plant-based ingredients is the use of chicken eggs.

The Portuguese were also involved with the development of the modern idea that wagashi are sweet. Until the Muromachi period, sweeteners were limited to honey; amazura, which was produced from sweet arrowroot; and mizuame, which was a glutinous starch syrup made from rice and other grains. From 1543 to 1641, when trade with Spain and Portugal was at its peak, the Portuguese began to import sugar into Japan on a regular basis. Later, during the Edo period, sugar was increasingly imported from China and Holland. The use of black sugar from the Ryukyu Islands and wasanbon—sugar produced in the Sanuki region in Japan—also increased at this time, as Japanese people continued to enjoy the taste of wagashi produced with this precious imported commodity. Thus, the flowering of this part of Japanese culture can be traced back to the coming of merchants from Portugal.

Wagashi and the Rinpa school of fashionable design

The Edo period was a time when a wide variety of wagashi gained popularity. During the period from 1596 to 1644, different types of wagashi were given poetic names. And from 1688 to 1704, as this practice reached its peak under the influence of the Rinpa school of design, new forms of wagashi were created with poetic names based on classic literature and flavors related to the four seasons. Onmushigashizu [を二-85], a sample book published by a wagashi shop, features many new designs of wagashi with poetic names, such as “Mine no akebono” (Mountain Peaks at Dawn). These names and designs will be introduced in the column “5 designs of wagashi.”

Dagashi is also wagashi—the world of ame-uri (candy vendors)

In the Edo period, the culture of dagashi (cheap sweets) blossomed among the public. It is said to have been a part of the wagashi culture. This paragraph focuses on dagashi candy. Candy in the Edo period differs slightly from modern candy, and is said to have been made primarily from grain-derived sweeteners, rather than sugar, which was rare at that time. The various aspects of the merchants who sold such candy have been preserved in many documents, with the help of the existence of unique candy vendors who will be described below.

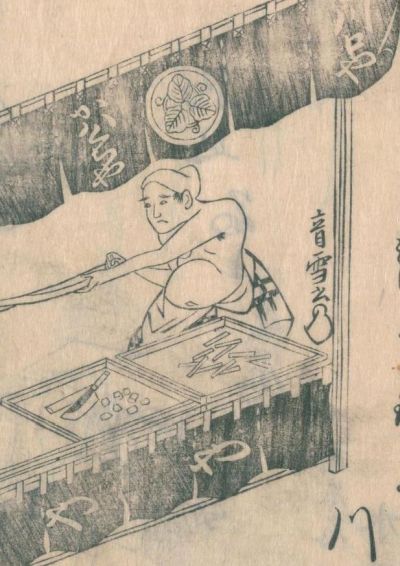

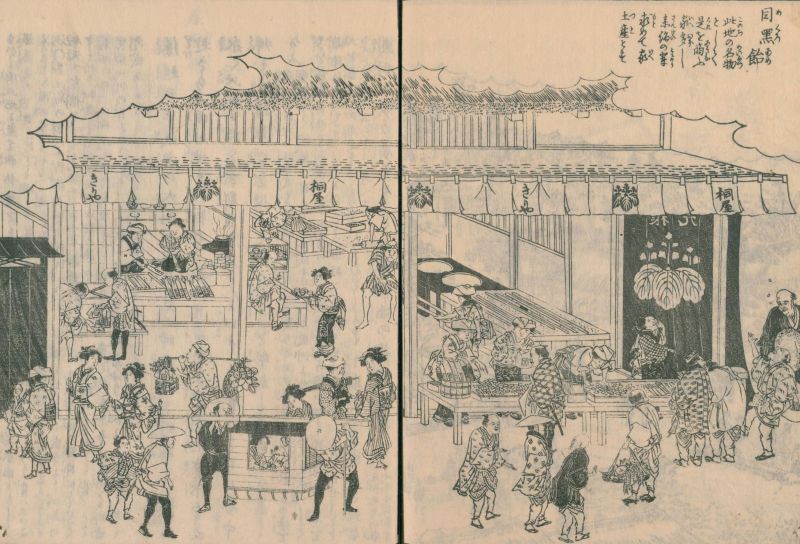

Candy shops in Meguro

A shop front view of Kiriya in Meguro.

Two people are stretching out candy on the right side of the shop, while others are bagging it at the front of the shop.

Candy is one of the specialties of Meguro, and candy shops such as Kawaguchiya and Kiriya were famous. Edo meisho zue introduces Kiriya, which sold Meguro ame. Meguro Fudoson (Ryusenji Temple) in the suburbs of Edo was a popular holiday destination in those days, and visitors to the temple bought it as a souvenir. A large paulownia crest can be seen on the front of the store and the name Kiriya can be seen on the shop curtain.

The name of Kiriya and the paulownia crest were famous as the symbol of a candy shop. In the scene of a teahouse in the picture story Meidai higashiyama dono [208-792], in which the characters are confectionery, you can see a paulownia crest on the shop curtain and the shop name Kiriya. This is also a rendition using the image of Kiriya as a candy shop.

2) Toyokuni, Ame-uri Sentaro, published by Etsuka in 1861 (in Azuma nishiki-e) [寄別8-5-2-3]

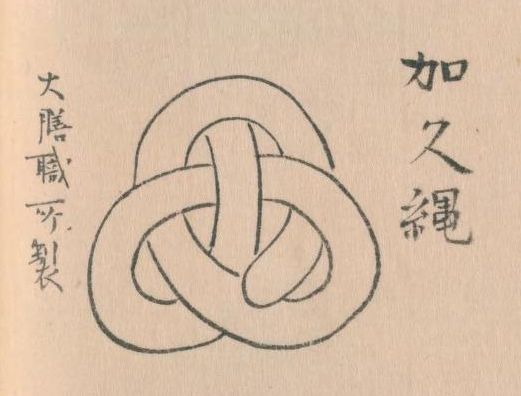

This is a nishiki-e by Toyokuni depicting the thirteenth ICHIMURA Uzaemon, a kabuki actor dressed as a Kamakura-bushi ame-uri (see below), whose costume has a pattern of tachibana and spirals. As well as the paulownia pattern mentioned above, the swirling pattern was known as the symbol of a candy shop. In the late Edo period, the Morisada manko [寄別13-41], which describes the customs in Edo, also introduced that all the candy shops in Edo displayed swirling patterns, and that some of the vendors nowadays also use them. Tachibana and the swirling patterns were originally the family crest of the Ichimura family, but here the swirling patterns overlap with the symbol of a candy shop.

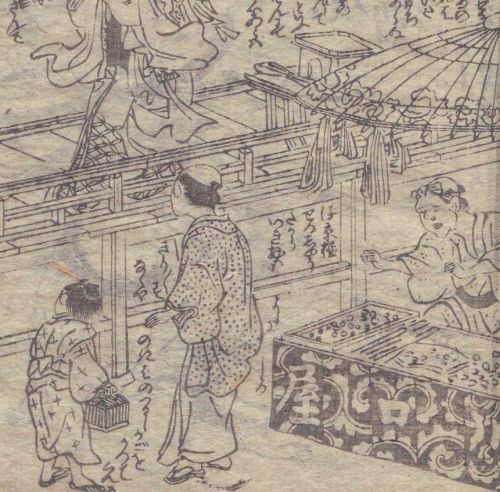

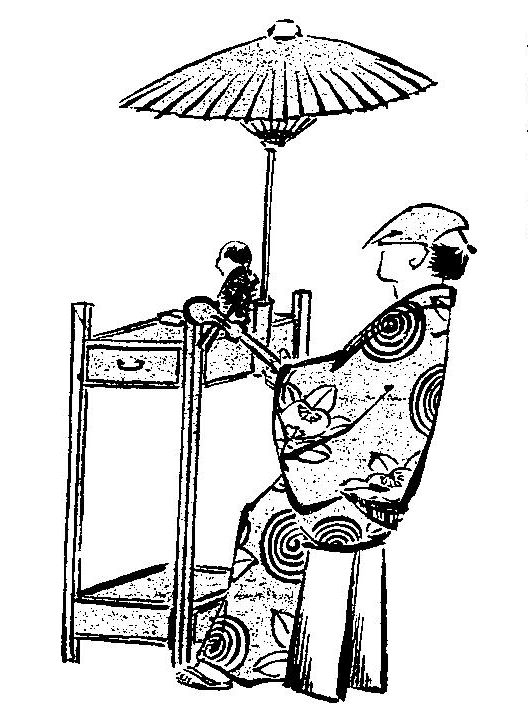

Kasa no shita shonin (merchants under umbrellas)

While there were some shops like Kiriya that sold candy on the main street, there were also many small-scale candy shops. According to Morisada manko [寄別13-41], wayside merchants called “kasa no shita shonin” could be found in the three cities: Kyoto, Osaka and Edo. They set up large umbrellas in busy streets and sold candy and other goods under them. It is said that the reason for holding an umbrella was to keep candy from melting in the sun or getting wet in sudden rain. It is thought that a painting in Doke hyakunin isshu [208-240] depicts it, and the person in the painting also sells something that looks like candy. In addition, the word "Kawaguchiya" is written on the front of the product stand, though it is slightly out of character.

The name Kawaguchiya was one of the two major brands of candy in the An'ei Era (1772-1781), along with Kiriya. In Buko nenpyo [213.6-Sa222b], it is mentioned that Kiriya in Meguro and Kawaguchiya in Zoshigaya were in fashion. According to Gofunai bikou [593-8], a geography of Edo compiled by the Edo shogunate, a person selling handmade candy appeared in the precincts of Kishimojin during the Shotoku era (1711-1716), and he named himself Kawaguchiya. It became so popular that even unrelated families started selling candy under the name of Kawaguchiya. In Ehon Edo-miyage [わ-54], a candy shop called Kawaguchiya is also depicted at the foot of Ryogoku Bridge, suggesting that the image of Kawaguchiya as a candy shop was widespread.

Ame-uri geinin (candy vendors performing feats)

Some of the vendors did not just walk around selling candy, but also tried to differentiate themselves by dressing in women's clothing or showing off karakuri dolls in order to attract customers.

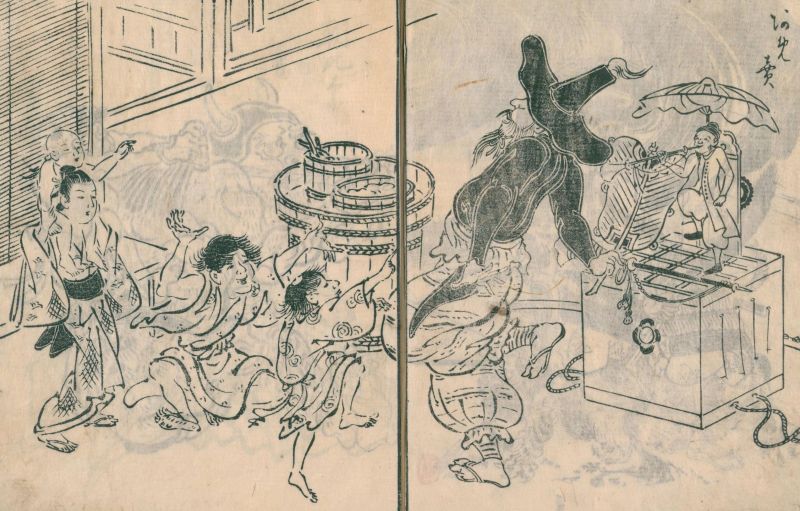

A painting in Hanabusa Iccho gafu [京-9イ] by HANABUSA Iccho (1652-1724) depicts a Tojin ame-uri who is thought to have appeared at the beginning of the 18th century, in the middle of the Edo period. The candy vendor, dressed in a Western-style costume, dances with children. The box on the right side of the candy vendor is a tool for attracting customers, nozoki karakuri, which shows foreign landscapes using paintings and dolls. To the left of the candy vendor is vats filled with candy. It is said that candy vendors often sold mizuame or jiosen-ame which was boiled down from mizuame.

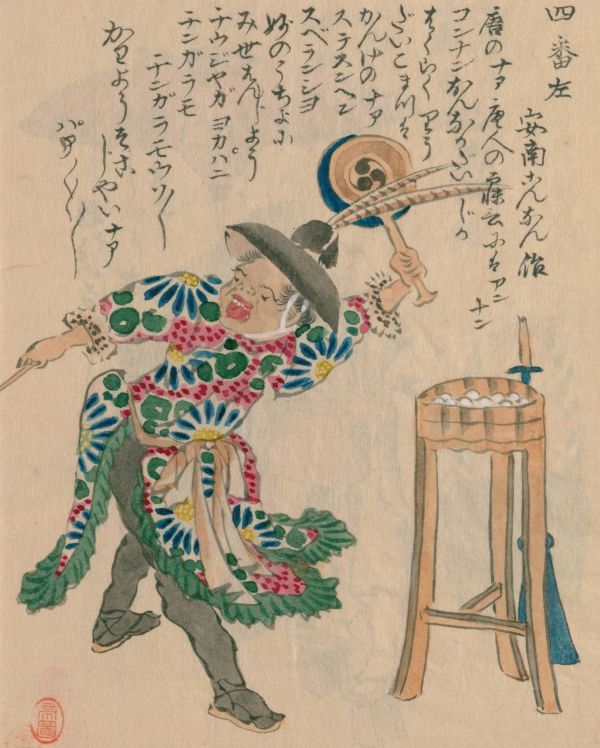

Next is Tojin ame-uri in the late Edo period. They gained popularity by singing funny songs about strange things, such as “annan konnan” (this and that), in Asian-style attire. Later, parodies appeared, and there were children in the town who sang songs by imitating them (Kinsei akinai zukushi kyoka awase [丑-44]).

There were other ways in which a single candy-selling performance like this could create a boom in the street. One of the most famous was Kamakura-bushi ame-uri (Edo funai ehon fuzoku orai [249-50]). It is said that in the Kan’ei era (1848-1854), a candy vendor singing and playing a shamisen on the streets appeared, and it was a great success: There was no time to lift up a load once it was unloaded, and there was a never-ending stream of requests for songs. When the 13th Ichimura Uzaemon (later the 5th ONOE Kikugoro) heard about this, he invited a candy vendor to his house to learn about it and performed it at the Ichimura-za, which was well received. It is said that the candy vendor was given a costume with the Ichimura family's crest on it and worked wearing it afterwards. The candy vendor in the painting also wears a costume with the Ichimura family crest of Tachibana and Uzumaki (a swirling pattern). The picture of the actor in the swirling pattern costume, Ame-uri Sentaro, introduced earlier, was played by Ichimura Uzaemon as the Kamakura-bushi ame-uri (Ame-uri Sentaro [寄別8-5-2-3]).

Different kinds of sweets vendors

In Baio zuihitsu [US1-E7], it is written that only candies such as mizuame and sakuraame had been sold by vendors, but that now a wide variety of confections was sold, including dried confections, manju, yokan, and uiromochi. At this time, various kinds of wagashi were already delivered to ordinary people by confectionery vendors.

Next Column:

5 designs of wagashi