- Kaleidoscope of Books

- WAGASHI

- Part 3: Wagashi in Japanese literature

- Introduction

- Part 1: A short history of wagashi

- Column: 5 designs of wagashi

- Part 2: Traditional events and customs involving wagashi

- Part 3: Wagashi in Japanese literature

- Epilogue/References

- Japanese

Part 3: Wagashi in Japanese literature

Part 3 introduces tales, poems, and theatrical works that depict wagashi, as well as tidbits related to them through their authors.

Man’yoshu poets writing about “kashi”

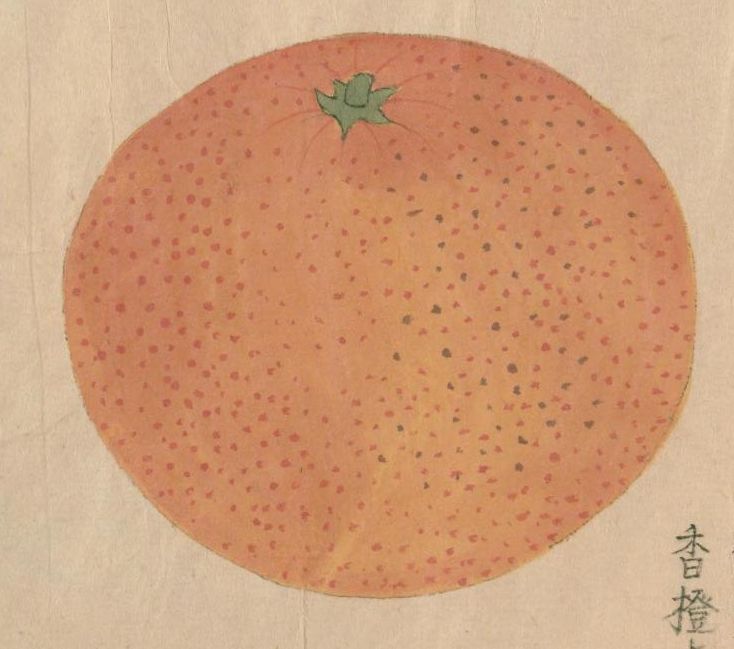

As mentioned in Part 1, before confectionery was made with bean paste, sugar, rice, and wheat, “kashi” referred to fruit. The Man’yoshu, Japan's oldest poetry collection, contains poems about old Japanese fruit trees such as peaches, persimmons, ume, plums, pears, loquat, tachibana, bayberry, jujube, and akebi.

吾妹子(わぎもこ)に 逢はず久しもうましもの 阿倍橘の羅(こけ)むすまでに

Wagimoko ni awazu hisashi mo umashi mono abetachibana no koke musu madeni

(It has been a long time since I have seen my beloved. The moss has grown on that Abetachibana tree.)

Man’yoshu [WA7-109]

There are various theories as to which species of citrus the Abetachibana refers to, such as citrus nobilis or bitter orange. The image shows citrus nobilis (香橙) painted by the late Edo period herbalist, MORI Baien.

In particular, tachibana was loved as the highest quality kashi to the extent that Emperor Shomu (701-756) said that tachibana is the top of kashi and liked by people, according to Shoku Nihongi [839-2]. As for traditions related to tachibana, there are descriptions in Nihonshoki [839-1] and Kojiki [830-151], and it is said that when Emperor Suinin (years of birth and death unknown) fell ill, Tajimamori (years of birth and death unknown) was sent to the tokoyo (a world without time, an unchanging ideal world) in search of tokijikuno kaguno konomi (tachibana). When he got it and returned, the emperor had already passed, so it is said that he died mourning in front of the mausoleum.

OTOMO no Yakamochi (718-785), a famous poet of the Nara period, used this tradition as a subject for his poem “Tachibana no uta isshu” (Man’yoshu No.4111), and saw eternity and prosperity in the tachibana, whose leaves did not fall throughout all the seasons.

Heian nobles liking “kashi”

Confectionery appears occasionally in the literature of the Heian period, and the descriptions not only appear delicious, but also describe gorgeous parties and elaborate preparations that give an impression of the Heian dynasty.

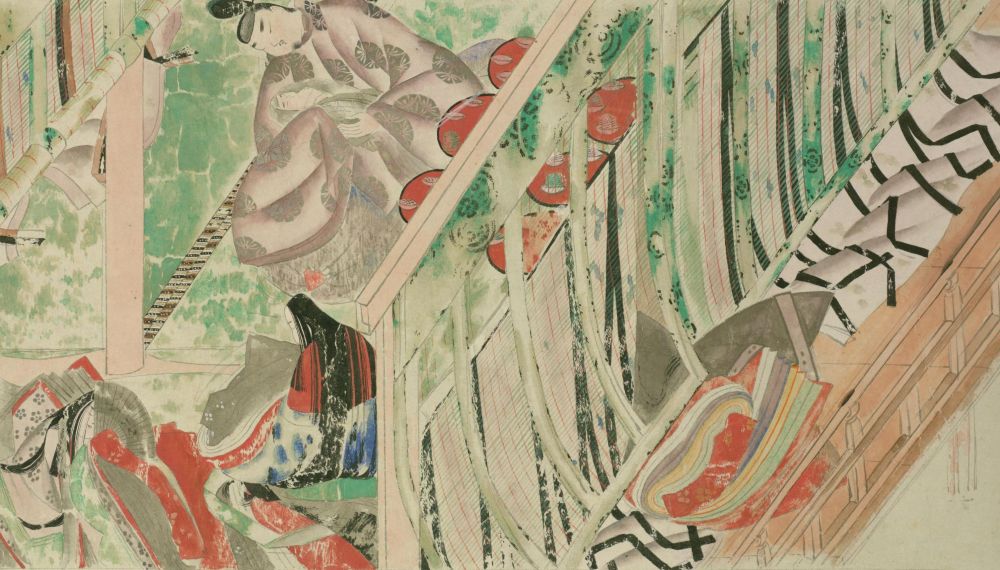

In “Yadorigi” in Genji monogatari (The Tale of Genji) [WA7-279], there is a scene in which Onna Ninomiya presents a confectionery called fuzuku to nobles. According to the recipe in Genchu saihisho [127-1], a commentary on Genji monogatari, it is a confectionery like rice cakes, made by grinding rice, wheat, beans, and other grains into powder and coloring them in five colors: blue, yellow, red, white, and black. It has a sweetness by itself, but is also served with amazura scented with musk in silver or lapis lazuli bowls, suggesting gorgeousness and luxury.

A scene from the celebration of Kaoru's 50th day after his birth in Genji monogatari: Kashiwagi. This ceremony to celebrate good health and well-being was considered important as “Ika no iwai (fifty-day celebration).” A variety of dishes and sweets are laid out beside Hikaru Genji, who is holding Kaoru.

In Makura no soshi (The Pillow Book) [WA7-141], another confectionery appears. Sei Shonagon (years of birth and death unknown) wrote the following about an episode in which “aozashi” was delivered to her when she was preparing to celebrate tango no sekku.

五月の菖蒲輿など持ちてまゐり。(中略)あをさしといふものを人の持てきたるを、青き薄樣を艶なる硯の蓋に敷きて、「これませこしにさふらへば」とてまゐらせたれば、

みな人は花やてふやといそぐ日もわがこころをば君ぞ知りける

と、紙の端を引き破りて、書かせ給へるもいとめでたし。

(I brought a palanquin of irises for Tango no sekku. (snip) A person took aosashi. I laid the thin, blue sheet of paper on the lid of the inkstone. I put aosashi on it and gave her it. I said “because it is over the fence,” and gave it. Then she tore the edges of the paper and wrote.

“Minahito wa hana ya cho ya to isogu hi mo waga kokoro oba kimi zo shirikeru”)

Aozashi is said to be a confectionery made by frying green barley, grinding it with a mortar, and twisting it into a thread. The lid of a beautiful inkstone box was covered with a thin piece of blue paper, and aozashi was placed on it to be presented to Chugu Teishi (Empress Teishi) (976-1000), an example of Sei Shonagon's thoughtfulness.

MATSUO Basho (1644-1694) wrote a haiku about this confectionery, “Aozashi ya, kusamochi no ho ni idetsuran,” which shows that it was eaten even in the Edo period. In the mid-Edo period, Japanese classical scholar ONO Takahisa (1720-1799) wrote in his essay Natsuyama zatsudan [860-36] that aozashi is a confectionery made from green barley, which was in ancient times eaten by nobility, and is the same kind of confectionery eaten by people today.

Enjoying mochi in Edo

Glutinous rice cakes, or mochi, are a ubiquitous element in celebrations of the New Year and other auspicious occasions in Japan, that are said to have been introduced from South East Asia together with rice cultivation. In ancient times, mochi was a favorite snack among the aristocracy, and during the Edo period, mochi or mochigashi became a popular food even for ordinary people. There are many instances of rakugo (comedy routines), kyogen (short comedic drama), and kabuki scripts that mention the various mochigashi produced at the time.

At the end of the year, ordinary people placed orders for mochi with wagashi shops, while samurai or wealthy merchant families pounded mochi at home.

In the kyogen Narihiramochi [6-364], ARIWARA no Narihira writes a poem about rice cakes on his way to the Tamatsushima-myojin Shrine as payment for the rice cakes. The poem is full of mochi: “Hito no yubizashi warabimochi, haji o kakimochi. Kanashimi no namida wa ame ya samegaimochi. Taki no shiromochi kannomochi, furu wa yukimochi korimochi, miroku no shusse ni awamochi to, kuriko no mochi to kurigoto o, yute wa mohaya yomogimochi...”. Incidentally, the samegaimochi that appears in the poem is a specialty of Samegai (in Omi-no-kuni), which prospered as a post town on the Nakasendo highway in the Edo period.

Warabimochi appears in the kyogen Oka dayu [329-287]. The story goes that a man, having forgotten the name of a delicious confection served to him by his father-in-law, wants his wife to recite Wakan roeishu [午-4], which reminds him of warabimochi from the passage “Shijin no wakaki warabi hito te o nigiri.” “Oka dayu” is another name for warabimochi, and it is said that its origins are based on a Chinese legend in Shiji or the fact that Daigo Tenno (Emperor Daigo) in the Heian period favored warabimochi and bestowed the rank of “tayu” (fifth rank) to it.

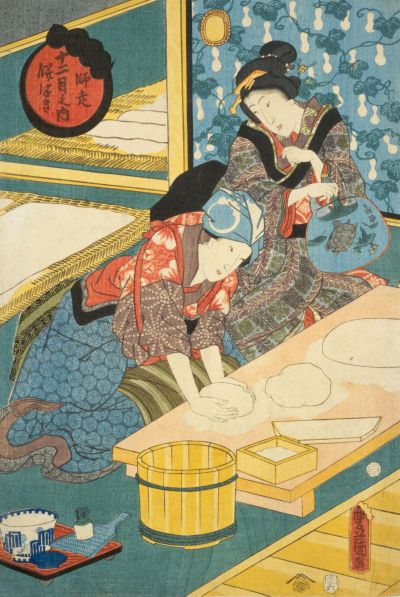

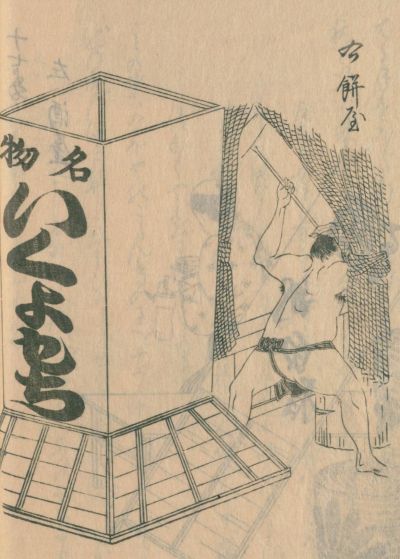

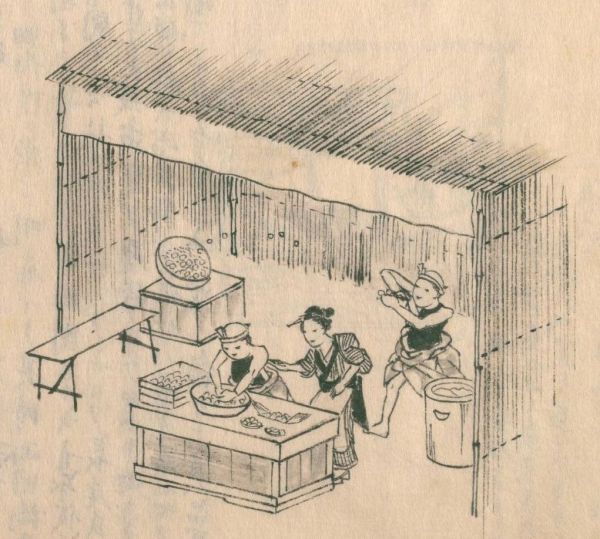

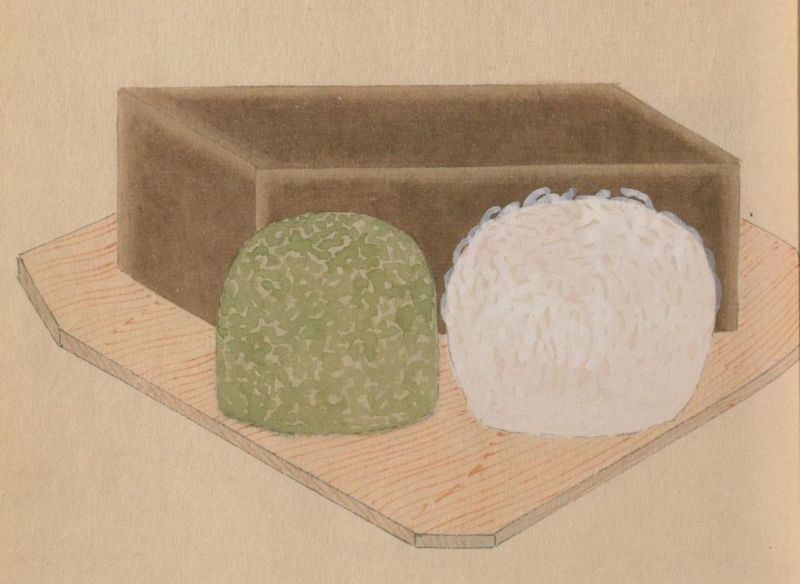

Ikuyomochi, which was the subject of a popular rakugo, is a type of anmochi which was a specialty of Edo, popular during the Genroku era (1688-1704). The name is said to have come from the fact that Ikuyo, who was a prostitute in Yoshiwara, was bought out by Komatsuya Zenbei, the head of a group who pulled shariki carts, and then sold this mochi at Komatsuya in Nishi-Ryogoku Hirokoji. In the rakugo story, Zenbei is replaced by Seizo, an earnest apprentice who works at a rice polishing shop, and Ikuyo is replaced by Ikuyo Tayu of Sugataebiya.

Awamochi is another type of rice cake that was loved by the common people in Edo. It is a yellow rice cake made from glutinous millet, and can be eaten by covering it with kinako or wrapping it in bean paste. In the kibyoshi Kinkin sensei eiga no yume [207-2] by KOIKAWA Harumachi (1744-1789), an awamochi shop in front of Meguro Fudoson appears as the setting for the story where the main character nods off and has a long dream while awamochi is being pounded.

In the late Edo period, there was an awamochi vendor who became quite well known for his humorous performances, called kyokuzuki, while pounding mochi with a mallet. A book on everyday life during the Edo period, Morisada manko [寄別13-41], tells of a kyokuzuki performer who amazed audiences with acrobatic performances that included chanting as he swung the mallet and throwing pieces of mochi into a dish from a distance. Kabuki performances featuring the pounding of mochi are still seen even today with titles such as Hana no hoka niwaka no Kyokuzuki, Chigiru Koi Haru no Awamochi, Awamochi, and Koganemochi.

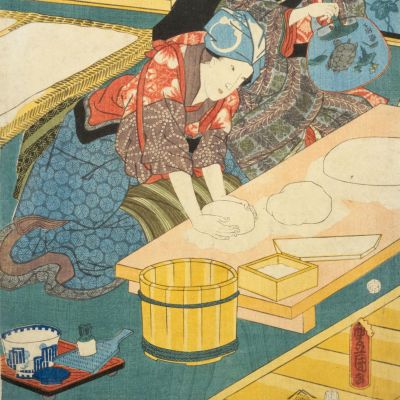

5) Toyokuni, Misuji no Tsunayoshi Kawarasaki Gonjuro, Awamochi no Antaro Nakamura Shikan, Awamochi no Kinazo Ichimura Uzaemon, published by Tsujiokaya in 1861 (in Azumanishikie) [寄別8-5-2-3]

This nishikie depicts the kabuki program Hana no hoka niwaka no kyokuzuki which was performed at Ichimura-za, a major kabuki theater in Edo, in February 1861. The picture vividly depicts the two awamochi vendors pounding mochi in matching costumes.

Great writers and poets loving wagashi

In the Meiji period (1868-1912), Western confectionery such as chocolate and caramel began to be imported from abroad, and domestic confectioners began to produce biscuits and drops. Cafe shops that served coffee and Western sweets also appeared, and they flourished during the Taisho period. On the other hand, it seems that there were many people who liked wagashi. The works of the writers who were active at the time show their characters enjoying wagashi, while essays and memoirs show us the writers themselves enjoying wagashi.

Enthralled by bean paste

The first thing that comes to mind when talking about the ingredients of wagashi is probably azuki bean paste. The main character in NATSUME Soseki's novel Kusamakura [913.6-N659k] likes yokan the most out of all sweets. He praises the beauty of the unique texture of yokan: “The smooth, precise, and translucent way its coating catches the light is a work of art. In particular, when kneaded to include a blue-tint it is like a hybrid of jade and agalmatolite, and is very pleasant to look at.”

Speaking of yokan, the female poet YOSANO Akiko was born in the long-established wagashi shop Surugaya, which was known for yokan. She helped with the family business, standing in the storefront and cutting yokan. There is a poem that seems to have been written about the memories of those days: “Obatachi to azuki o yorishi katawara ni shiragiku sakishi ie no omoide (I was selecting azuki with my aunt besides the white chrysanthemums were blooming)” (Shuyoshu [651-11]). In later years, Akiko's eldest son, YOSANO Hikaru (1903-1992), wrote in his book Akiko to Hiroshi no omoide [KG634-E79], "My mother used to make oshiruko fairly often. In other people's houses, zenzai, you know, is made of unmashed azuki beans. My mother, who is the daughter of a yokan shop, didn't make zenzai or similar things because she thought they seemed unfinished. Always oshiruko.”

AKUTAGAWA Ryunosuke also seems to have had a strong attachment to shiruko. Akutagawa was known as a non-drinker and sweet tooth. In his short essay Shiruko [775-240], he wrote, "We can no longer taste the ‘okina' of Tokiwa in Hirokoji served in a bowl," as he lamented that his favorite shiruko shop had disappeared due to the Great Kanto Earthquake. His love of shiruko is described in detail in the essay Kuishinbo [914.6-Ko715k] by his friend KOJIMA Masajiro (1894-1994).

Wagashi lined up

There are so many sweets lined up in front of the sweets shop or at the sweets buffet that it's a sight to behold and a treat for those with a sweet tooth.

NAGAI Kafu (1879-1959)'s Maitsuki Kenbunroku [918.6-N128k], dated February 5, 1917, states that from February 5 to March 30, 1917, a "Zenkoku meisan kashi chinretsu kai" was held at Shirokiya Gofukuten. According to his memo, there were many famous sweets from all over the country, including candy from Kumamoto, yokan from Wakayama, yatsuhashi and yoru no ume from Kyoto, kuriokoshi from Osaka, tsuki no shizuku from Kofu, gokaho from Saitama, kiraku sembei from Kanagawa, tochi yokan from Osaka, isobe sembei from Gunma, Nikko yokan, kokonoe from Sendai, choseiden from Kanazawa, mizuame from Takada, koshi no yuki from Nagaoka, yumoshi and kibidango from Okayama, tamago somen from Hakata, castella from Nagasaki, kalkan and buntanzuke from Kagoshima, and maruboro from Saga.

MASAOKA Shiki also seemed to have enjoyed sweets. In his later years, he suffered from a serious illness and could not go out as much as he wanted, but friends and disciples brought various gifts to him. Bokuju itteki [WB12-39], published in the newspaper Nihon [新-9] in February 1891, mentions names of various confections, such as noshiume from Yamagata, apple yokan from Aomori, okoshi from Osaka, yatsuhashi sembei from Kyoto, fish sembei from Mikawa, tsuki no shizuku from Koshu, candy from Kumamoto, and mizuame from Yokosuka, among other specialties such as meat, fish, and vegetables from all over Japan. The various confections must have amused Shiki on his sickbed.

Wagashi as characters of stories

Perhaps because they are familiar to us, stories have been created throughout the ages with confectionery as the characters.

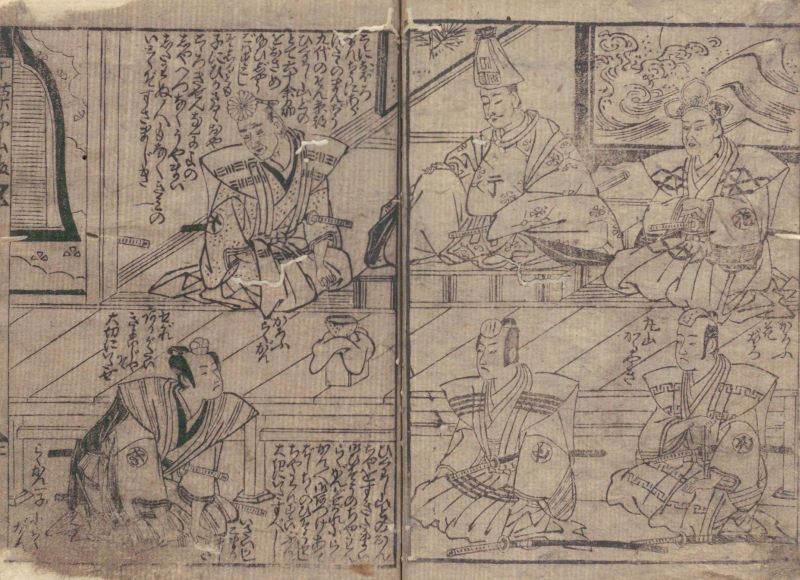

6) TORII Kiyonaga, Meidai Higashiyamadono vol.3 [208-792]

The kibyoshi Meidai Higashiyamadono, written by Torii Kiyonaga (1752-1815) in the middle of the Edo period, is a comical story in which all of the characters are wagashi. The main character, Korakugan, goes on a journey with his lover Matsukaze (wagashi with sesame and mustard seeds sprinkled on the front side of the dough) to get back the tea bowl belonging to his master, Higashiyamadono, which was stolen by the villain, Kompeito. Incidentally, this "Higashiyamadono (干菓子山殿)" is a pun on “Higashiyamadono (東山殿),” or ASHIKAGA Yoshimasa (1436-1490), the eighth shogun of the Muromachi Shogunate. The image shows the main character, Korakugan (bottom left), taking care of the tea bowl, with his master Higashiyamadono in the center and Korakugan's father Rakugan, the retainer, next to Higashiyamadono on the left.

In 1922, in the children's story Kyarameru to amedama [KH753-1] by YUMENO Kyusaku (1889-1936), not only Japanese sweets but also Western sweets appeared. In this short story, the caramels and other Western confections and the candy balls and other Japanese confections in a candy box fight over their taste and quality. As the two sides wrestle with each other, they get stuck to each other. It is said that the author's satire of the unstable world situation at that time is included in the funny but sad ending that human beings break them apart with a hammer and turn them into treats.

On the other hand, it was also the stories related to confectionery that energized children after the war. The manga Anmitsuhime [Y16-2605], drawn in 1951, features Anmitsu Hime who lives in Amakara castle as the main character, and characters named after wagashi such as Kasutera Fujin, Awadango-no-Kami, Ohagi-no-Tsubone, Abekawa Hikozaemon, Manju, Shio-mame, Dango, Shiruko, Kanoko, Anko, Kinako, and so on, creating a lot of adventures and commotion. It captured the hearts of children at a time when they didn't have as much sweetness as they do now.

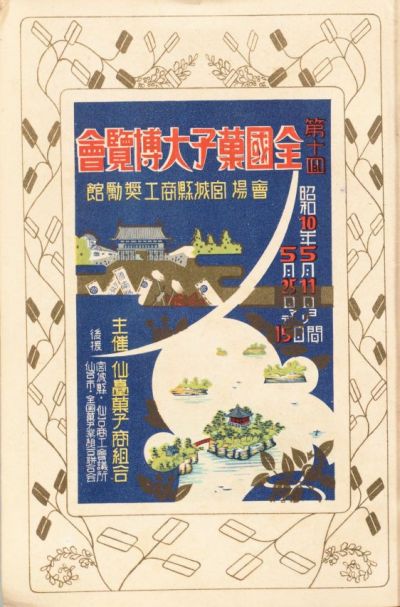

Column: Sweets festival—The National Confectionary Exposition

The National Confectionary Exposition, which was held for the 27th time in 2017, has been held over more than a century. This exhibition started in 1911 as the “Teikoku kashi ame dai himpyokai (Imperial Confectionery and Candy Competition)” at Sankaido in Akasaka Tameike, Tokyo, and since the 10th exhibition held in Sendai in 1935, the current name has been used.

A total of 536 items were exhibited in the categories of steamed confections, glutinous rice cakes, fresh confections, buns and ceremony confections at the 10th Exposition. Of these, 378 items were judged, including azuki rakugan from Akita, dried confectionery from Tokyo, and tamago somen from Fukuoka, which were selected as honorary gold medals for further refinement and excellence in quality design techniques.

Next

Epilogue/References