- Kaleidoscope of Books

- WAGASHI

- Part 2: Traditional events and customs involving wagashi

- Introduction

- Part 1: A short history of wagashi

- Column: 5 designs of wagashi

- Part 2: Traditional events and customs involving wagashi

- Part 3: Wagashi in Japanese literature

- Epilogue/References

- Japanese

Part 2: Traditional events and customs involving wagashi

Part 2 introduces wagashi that have appeared in annual events and are known as local specialties.

Annual events and wagashi—wagashi in daily life

The custom of eating special dishes at events throughout the year and at milestones in people's lives has existed since ancient times. This paragraph specifically focuses on the annual event called sekku, and life events that involve eating sweets.

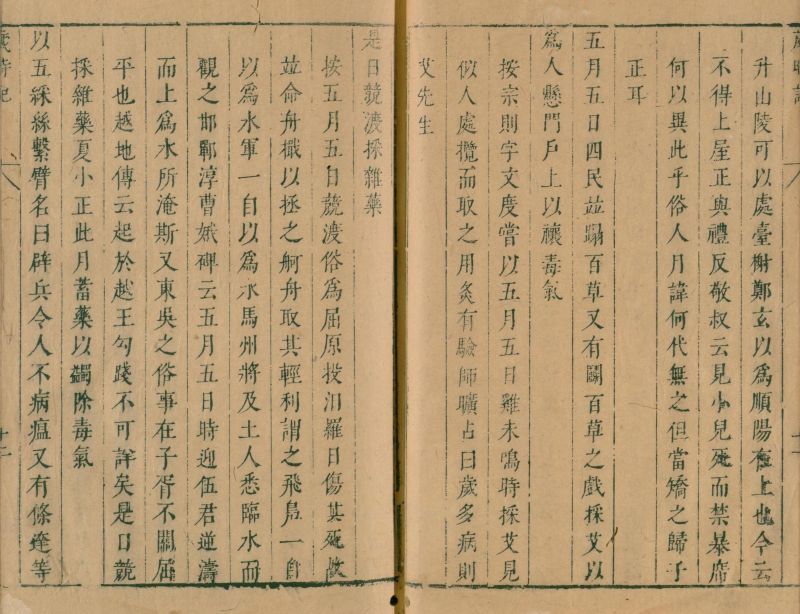

Sekku are days of celebration that are still celebrated today, such as Momo no sekku (Girls’ Festival) and Tango no sekku (Boy’s Festival), but originally the word meant “sechinichi no kugo.” “Kugo” was an offering made to the gods on a seasonally designated day (sechinichi). In the ancient Chinese literary calendar Keiso saijiki [特7-265], there are descriptions of sechinichi and offerings, and some of them became Japanese sekku almost exactly as they were.

In Japan, there is a section in Ryo no gige [WA17-6] (an annotation of the Yoro ryo), established in 833, which stipulates that the first 7 days of the new year are sechinichi, indicating that at the time, sechinichi and related rituals were held in Japan. As time went on, five of the many sekku—the seventh day of the New Year (Jinjitsu), March 3 (Joshi), May 5 (Tango), July 7 (Shichiseki), and September 9 (Choyo)—came to be regarded as important holidays. The Edo Shogunate established these 5 sekku as shikijitsu (fixed days associated with specific events). Here are a few of them.

Joshi

Joshi is the first day of “Mi (Snake)” in the third month of the lunar calendar. This day, known in modern Japan as the Girls' Festival, originated in China as a form of purification ceremony in which water and drinking peach blossom wine were used to drive away evil. According to the Keiso saijiki, in ancient China, on the third day of the third lunar month, people ate “ryuzetsuhan,” which is the juice of gogyo (Jersey cudweed) mixed with rice flour and nectar. In Japan, there is a record in the Heian period (794-1185) history book Nihon Montoku tenno jitsuroku [839-5] that it was an annual event to make kusamochi using gogyo on the third day of the third month of the lunar calendar, which may have been influenced by Chinese customs.

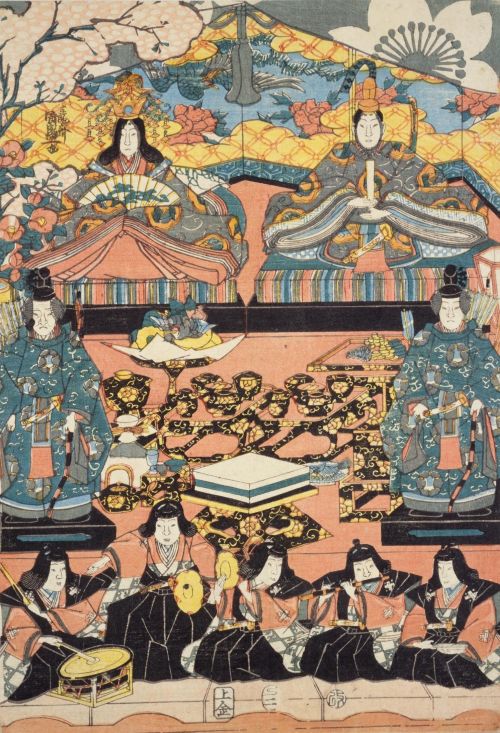

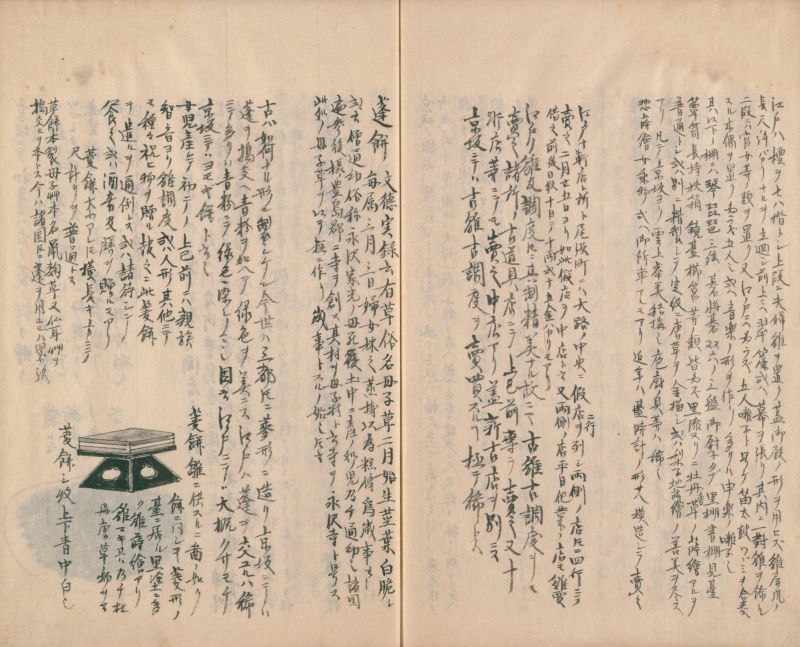

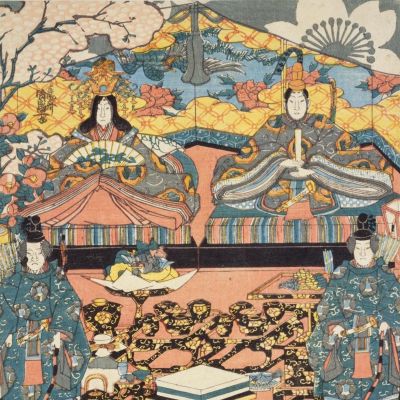

The tradition of eating kusamochi on the third day of the third month of the lunar calendar continued after that. By the Edo period, however, hishimochi had come to be used as a sweet to serve on the third day of the third month. A picture of a hishimochi is included in the Morisada manko [寄別13-41], which we mentioned in Part 1. According to it, hishimochi in the Edo period were often three layers of green-white-green instead of the now common red-white-green. However, it is possible to see from our collection that not all hishimochi were made in this way. Omochae [寄別3-1-2-4], published in 1857, is a good example. Omochae is a type of ukiyoe print which was designed for children to play with, and was popular from around the Ansei era (1854-1860) to the middle of the Meiji period. In this print, which was published close to the time of the compilation of Morisada manko, hishimochi are three layers of white-green-white. Some of the ukiyoe of the Girls’ Festival depict hishimochi in five layers of white-green-white-green-white, and this variety is interesting.

Morisada manko is characterized by the fact that it often compared the customs of Edo with those of Kyoto and Osaka. The paragraph on “yomogimochi” that follows “the third day of the third month” deals with the customs of both the Edo and Kamigata (Kyoto-Osaka) areas, and says that in Kamigata, a sweet called “itadakimochi” was handed out. This confectionery, with one side of the rice cake picked up and topped with bean paste, is called “Akoya” because its shape resembles a pearl oyster, and “Hikichigiri” because the tip of the confectionery is torn off.

3) Morisada manko edited by KITAGAWA Kiso [寄別13-41]

One of the most important documents on customs in the Edo period, written by Kitagawa Kiso (Morisada) (1810-?). The contents of the book include about 700 names and events, categorized into 27 themes with explanations. It remained in manuscript form and was not published in the Edo period. This material is a manuscript of Morisada's own handwriting in our collection.

As we have mentioned many times in this exhibition, this document contains descriptions of sweets throughout. It could be said that confectionery was pervasive in various scenes of daily life in the Edo period. In Koshu vol.1 “Shokurui (foods)”, there is also a paragraph “kashi,” from which we can learn about the state of confectionery in the late Edo period, along with other paragraphs such as “mochi,” “yokan,” and “manju.”

Tango

Originally, Tango was the day of “Uma (horse)” at the beginning of a month and was not limited to the fifth month, but after the Han Dynasty in China, it is said to have come to mean the fifth day of the fifth month. Since ancient times, iris (shobu) has been used to ward off evil spirits, but since iris (shobu) is connected to shobu (martial spirit), it was celebrated by samurai families and became established as the Boys' Festival in the Edo period.

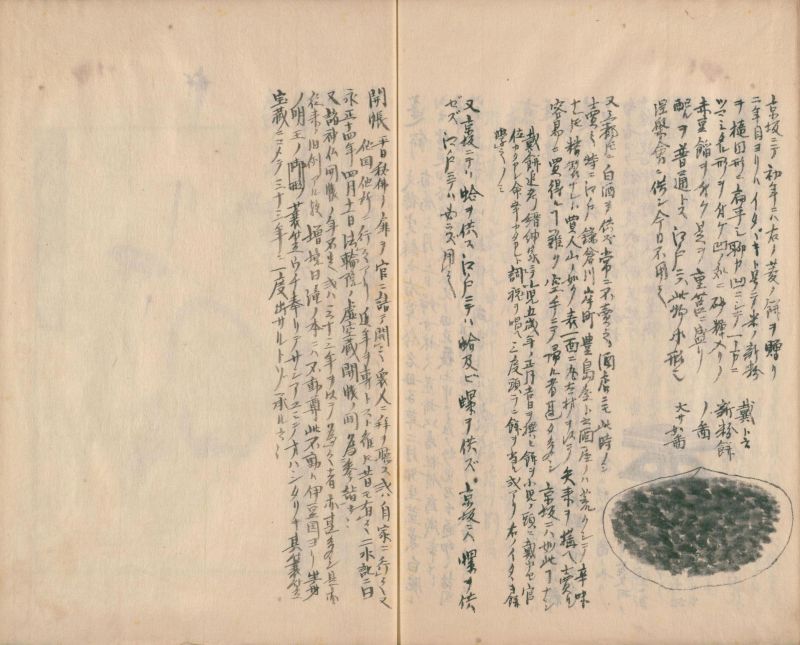

Chimaki and Kashiwamochi are the most famous sweets that appear on Tango no sekku. Chimaki also appeared in the Heian period dictionary Wamyo ruijusho [WA7-102], where it is described as being eaten on the fifth day of the fifth month. However, it is described as being made by wrapping rice in wild rice leaves and boiling it in lye, and it seems not to have been a sweet food. Although it is not clear when sweet chimaki became popular, Morisada manko contains a description of the chimaki of a confectioner named Kawabata Doki in Kyoto, indicating that sugar was first used for chimaki in the Edo period at the latest. As in the case of hishimochi, the Morisada manko also describes the events of the three cities that celebrated Tango no sekku. According to it, in Kyoto and Osaka people gave chimaki to their relatives on the first Tango no sekku after the birth of a boy, and kashiwamochi from the second year onwards. In contrast, in Edo, kashiwamochi were given from the first year of the birth.

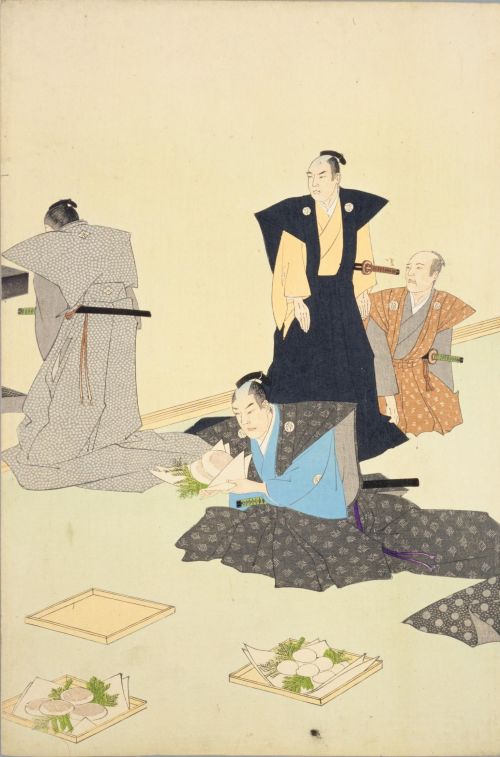

Kajo

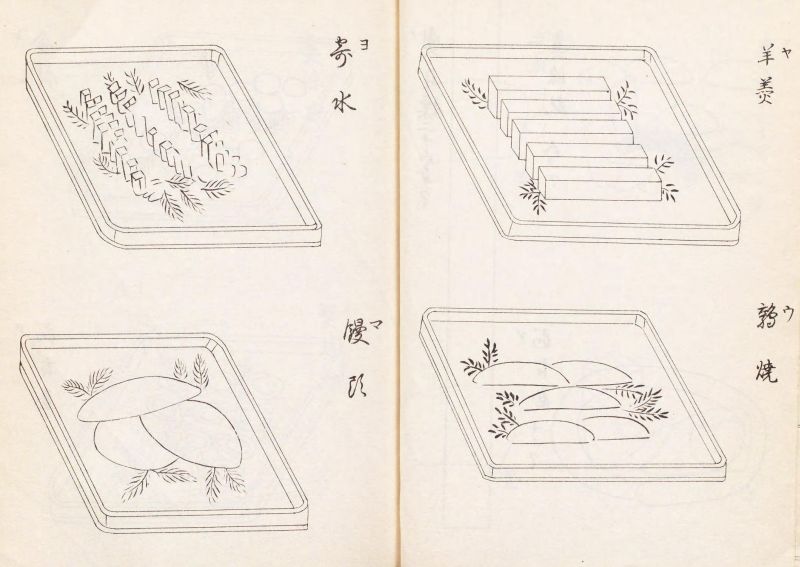

Although it was not sekku, on the sixteenth of the sixth month, an event called Kajo was held in which sweets played an important role. The origin is not certain, but there are many descriptions of the event in the records of the Muromachi period. In particular, samurai families played a game of shooting yokyu (a short toy bow), where the loser bought food with 16 Song dynasty coins, known as “Kajotsuho,” and gave it to the winner. A court noble in the Muromachi period, ICHIJO Kaneyoshi (1402-1481), in his book Segen mondo [853-233], suggested that it became popular because the characters of “Ka” and “Tsu” were similar to “katsu (win).” During the Edo period, Kajo was considered an important ceremony day, and daimyo (feudal lords) and shogunal retainers went to Edo Castle to receive sweets from the shogun. According to the Tokugawa reitenroku [210.5-M283t], a collection of documents on the rituals and regulations of the Edo Shogunate compiled during the Meiji period, the confections prepared on Kajo and their quantities are as follows:

196 sets of 3 manju, total 588

194 sets of 5 yokan, total 970

208 sets of 5 uzurayaki, total 1,040

208 sets of 12 akoya, total 2,496

208 sets of 15 kinton, total 3,120

208 sets of 30 yorimizu, total 6,240

194 sets of 5 hirafu, total 970

196 sets of 25 noshi, total 4,900

On the day before Kajo, they were placed on hegi (square trays made from thinly stripped boards) and laid out in the great hall of Edo Castle. Then, it is said that someone prepared for the day by staying awake the night before.

Kajo was abolished in the Meiji period, but in 1979, the Japan Wagashi Association established June 16 as “Wagashi Day” after Kajo.

Wagashi as local specialties

In the Edo period, confections known as specialties appeared in the three cities of Kyoto, Osaka, and Edo, as well as in various parts of Japan. These were further recognized by the fact that they were written about in various meisho-zue, books on customs, travelogues and literary works on the theme of travel.

Appearance and spread of jogashi

As society became more stable in the Edo period, the amount of imported sugar, which had previously been a scarce product, increased, and a variety of confections were made. One of them was jogashi, which came to be made mainly in Kyoto in the early Edo period. Jogashi was a premium confectionery made with expensive white sugar, but it is also said that it is “kenjo gashi (offered confectionery)” for the imperial court, shogunate, noble families, daimyo, and temples.

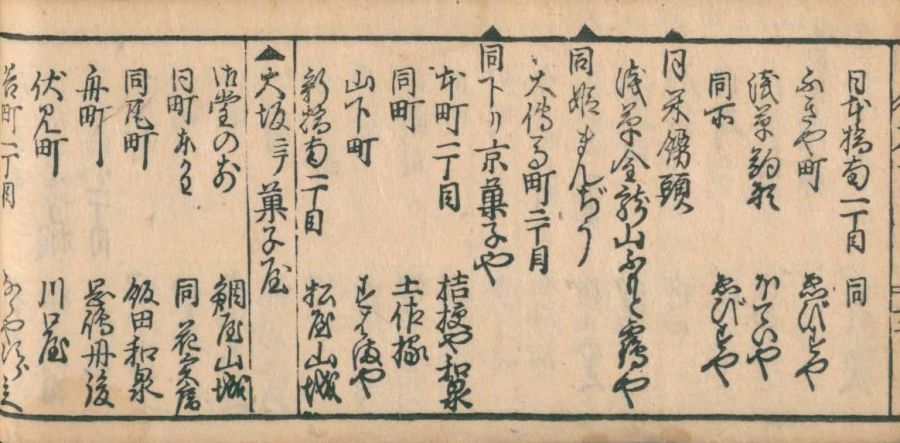

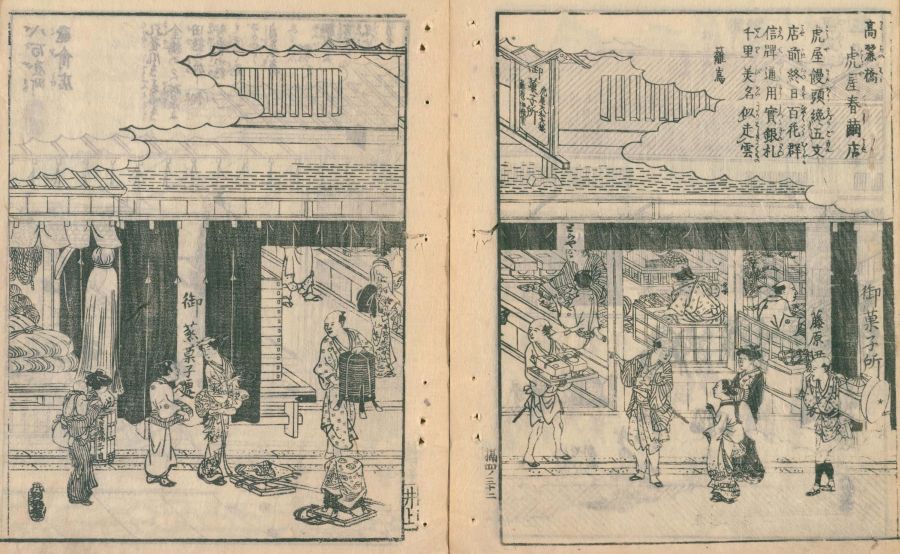

In Edo, goods coming from Kyoto, Osaka, and other places in the Kamigata region were prized as “kudarimono.” This is also the same for confectionery, and there were several confectionery shops in Edo that called themselves “kudarikyogashiya.” Yorozu kaimono chohoki [本別13-19], published in 1692, is a shopping guide that lists the famous shops of the time, and four kudarikyogashiya appear in it as well. Jogashi, which came to Edo from Kyoto as kudarimono, spread throughout Japan due to sankinkotai, as described later.

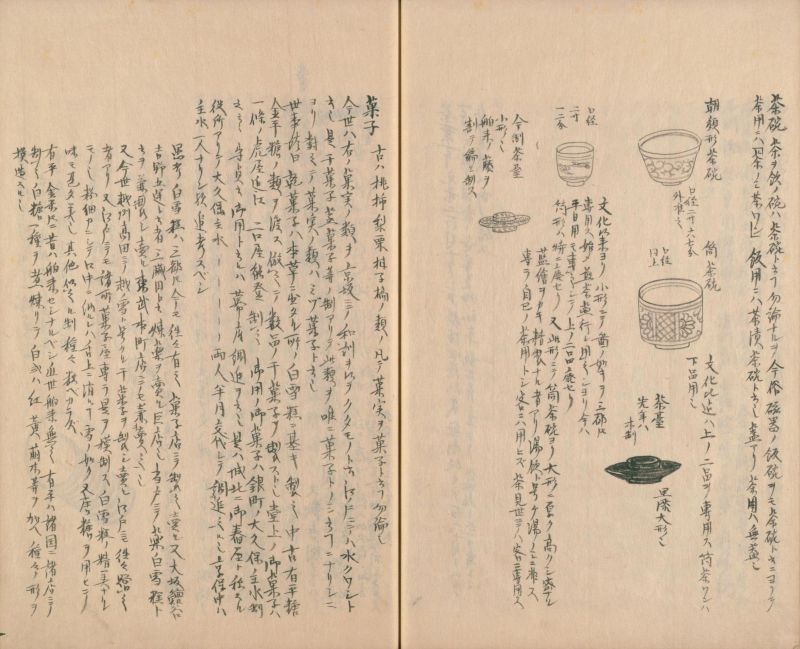

Kashi of 3 cities

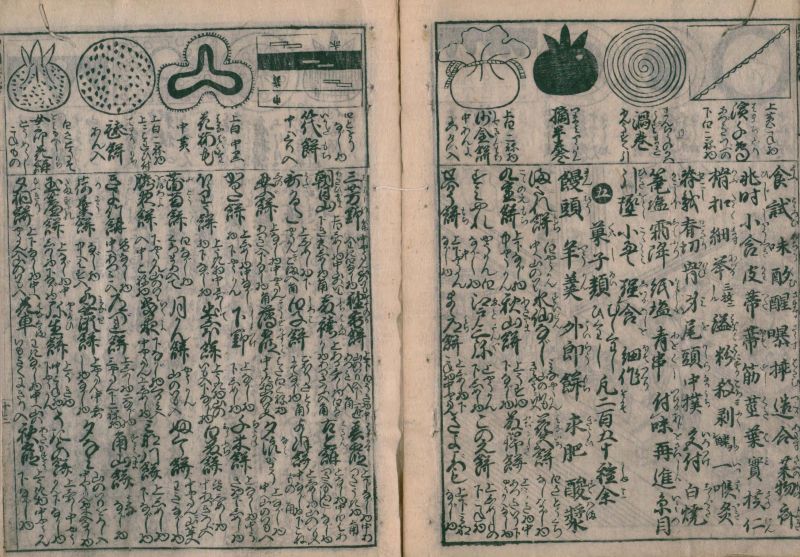

The Genroku era (1688-1704) is an important period in the history of wagashi. A cookery book, Gorui nichiyo ryorisho (in Edojidai ryoribon shusei shiryohen [W435-4] 2), of which the second volume of the five volumes covers the manufacturing process of confectionery, was published in 1689, and Nan chohoki [111-234], which features a lot of steamed and dried confectionery, was published in 1693. Although Nan chohoki is an instructional book on art for men, kashi-rui is listed alongside chanoyu and ikebana, suggesting a relationship between chanoyu and wagashi. The encyclopedia Wakan sansai zue [031.2-Te194w-o], published during the Shotoku and Kyoho eras (1711-1736), also contained an entry on kashi in the section “zojo” in volume 105.

It was around the end of the Genroku period that recipes for confectionery began to be published independently of cookery books. In 1717, Gozen kashi hidensho [159-74] was published, and in 1761, Kokon meibutsu gozen kashi zushiki (in Kashi bunko [W435-7] No.1 and 2) was published. Gozen kashi hidensho lists many Nanbangashi (European confectionery), but the Kokon meibutsu gozen kashi zushiki lists an increasing proportion of wagashi and more detailed descriptions about it. It suggests that the status of wagashi seems to have improved over half a century. One of the foods for which the recipe is mentioned in Gozen kashi hidensho is bread. The word “波牟 (pan; bread)” also appears in Wakan sanzai zue (volume 105) , but as can be seen from the explanation of “蒸餅即ち饅頭に餡無きもの (steamed rice cakes, that is, manju without bean paste),” bread was considered to be manju without bean paste. However, the Gozen kashi hidensho describes using yeast and baking bread after it rises, and it is noteworthy as a document of the Edo period that describes the process of baking leavened bread.

There was also a genre of publication established during the Genroku period called yakusha hyobanki (reviews about kabuki actors). They were published mainly in the three cities of Kyoto, Osaka, and Edo, describing the looks and skills of kabuki actors. In the Horeki and Tenmei eras (1751-1789), a parody of them which featured confectionery as the subject, meibutsu hyobanki (reviews about specialties), also appeared. Fukijizai (in Tokugawa bungei ruiju [918.5-To426-K] No.12), published in 1777, describes the three cities of Kyoto, Edo and Naniwa (Osaka). “大至極上々吉 京の水 (Greatest and best; water of Kyoto)” is listed at the beginning of all the volumes, and confectionery shops appear in the foods and beverages section. The number of articles in the foods and beverages section of Kyoto is 19 in total, which seems to be less than in Edo (see below), but this may be due to the fact that the pages are devoted to sections not found in Edo (such as the talented women section, which deals with a koto player, calligraphers, and doctor), and the fact that confectionaries for the Imperial Court are not included. Edo devotes one section to confectionery, and 28 shops are featured, including “評判のひびき渡る唐ぐわし 鈴木越後 (the high reputation for togashi, Suzuki Echigo).” Naniwa does not take the form of a ranking, listing specialties such as Dojima's “米の立チ相場 (a quotation of rice).” There were only five confectionery shops mentioned, and one of them had “Toraya's manju stamps." These were equivalent to present-day gift certificates, and Toraya's stamp is depicted along with the shop's reputation not only in Fukijizai but also in Settsu meisho zue [839-77]. As for the “manju stamps,” the “manju” section of Morisada manko (Koshu vol.1) also mentions them along with the situation in Edo.

In the next year, Kyoto meibutsu mizu no fukiyose (Tokugawa bungei ruiju, No.12 [918.5-To426-K]) was published. Its rankings are the same as those of Fukijizai, but each one has the comments of todori (a leader) and migosha (kabuki dramatic critics and audience with a critical viewpoint). For example, in the case of the confectionery shop named Kameya Yoshiyasu, which was listed at the top of the ranking, people said that they will not accept it as the head of the foods and beverages section, and that there must be more successful local shops in Kyoto. In response to this, todori said that many shops and specialties have existed, but that each of them had only one unique feature, whereas Kameya Yoshiyasu accepts requests for any kind of confectionery, and for steamed confectionery especially, no one can compete with it. Migosha also comments on the degree of steaming, the color of the confectionery, and even the container in which the confectionery is placed (a nest of boxes with taka makie). In the end, todori concludes that Kameya Yoshiyasu is among the best in the recent past, and that he looks forward to its new product. It is interesting to note that the description in this paragraph indicates that the confectionery was made to order.

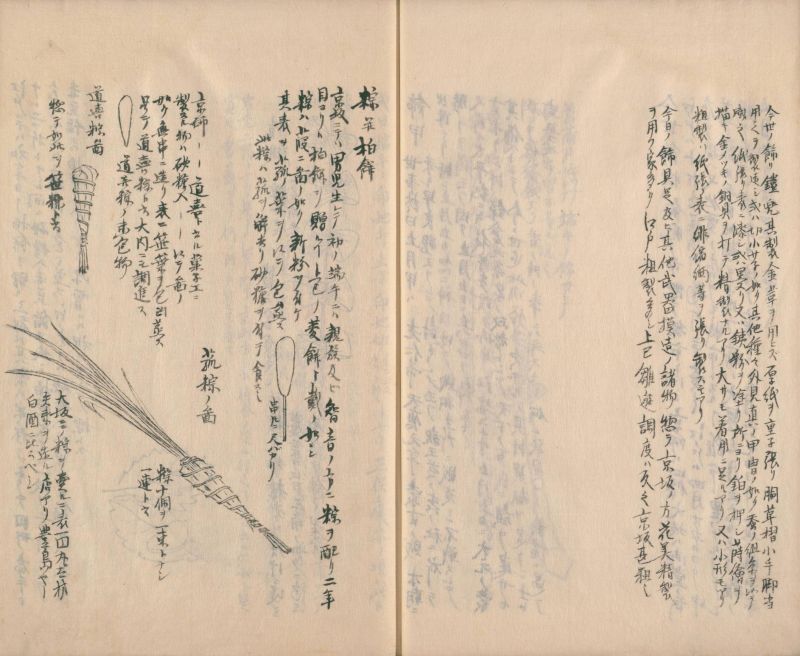

Meibutsu-gashi

In the Edo period, a transportation network including highways was developed. Eventually, many people, regardless of their status, began to travel, including daimyo doing sankin-kotai and people on pilgrimages to Ise. It was during this period that confectionery was sold as a specialty of cities or highways, in entertainment areas or in front of temples and shrines where people gathered, and was enjoyed by a variety of people. There are many descriptions of food in travelers’ diaries, the records of those who traveled, and it can be seen that there were so-called meibutsu-gashi in each place and that they were widely known.

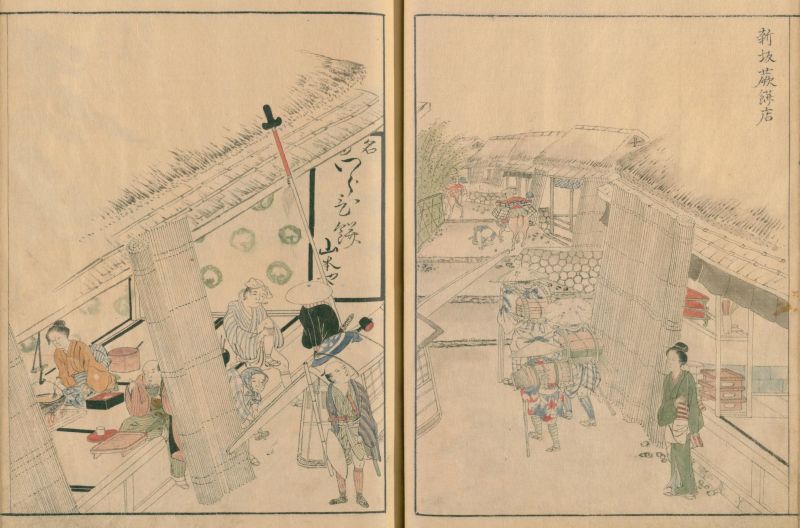

Some of these records were written later, not as diaries but based on what had been seen and heard through the author’s travels, and one of them is Togai benran zuryaku [さ-67], written by a samurai of the Owari Domain, KORIKI Enkoan (Tanenobu). The seven-volume autograph manuscript (owned by the Nagoya City Museum) includes illustrations and captions, but the one in our collection is thought to be a transcription from the late Edo period of part of the manuscript, and lacks the captions. It is said to have been completed slightly earlier than the Tokaido meisho zue [839-82] published in 1797, but as does the Tokaido meisho zue, it depicts not only famous and historic sites but also local specialties including confectionery.

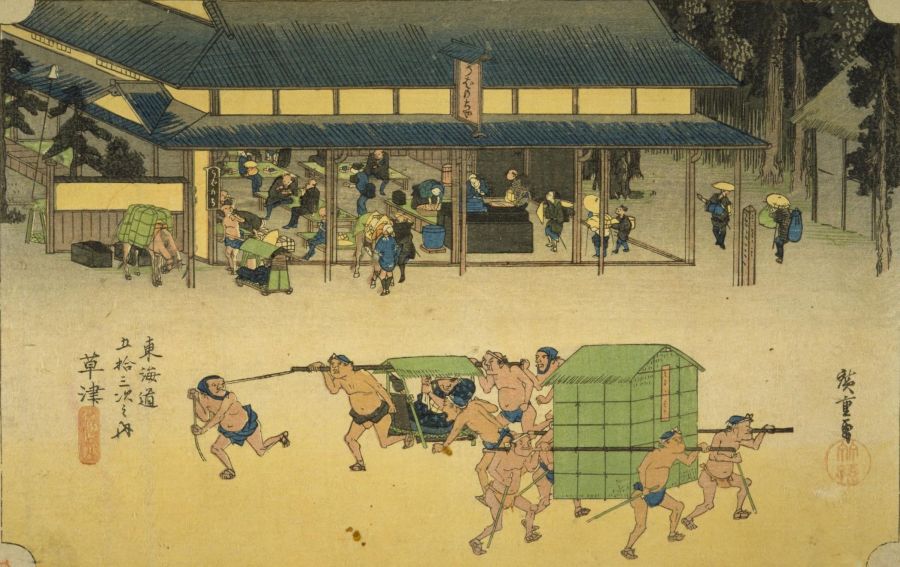

From the middle of the Edo period onwards, traffic along the road became more active, and popular journals called “meisho-ki” or “meisho zue” were published, which featured famous places, historic sites, scenic spots, and specialties in each region. Ukiyoe paintings with the theme of highways also appeared, as represented by UTAGAWA Hiroshige's Tokaido gojusan tsugi [寄別2-2-1-6]. In addition, a guidebook-like literary work, Tokaidochu hizakurige [120-53], was published and very well received. In these works, many foods considered local specialties were featured, including many confections that are still famous today. There are many famous confections in Tokaido in particular, such as abekawamochi (Shizuoka City), utsu no todango (Shizuoka City), nissaka no warabimochi (Kakegawa City), and kusatsu no ubagamochi (Kusatsu City), and their names became even more widespread as they were repeatedly depicted in various works.

4)KORIKI Tanenobu, Kitsui mudamakura haru no mezame in Sun’enzu sosho 3 [特260-207]

(Right) The right is Abekawamochi and the left is Warabimochi of Nissaka

(Left) Amenomochi of Sayo no Nakayama

This is a kibyoshi (a kind of novel of the Edo period) written by Koriki Enkoan (Tanenobu) (1756-1831), the author of Togai benran zuryaku in 1796. The storyline is that the specialties featured in Togai benran zuryaku gather to celebrate its completion.

In the same way as Meidai Higashiyamadono [208-792], which is introduced in Part 3, the author personifies the famous places and specialties of the Tokaido road depicted in Togai benran zuryaku, and describes the drama on the road, interspersing them with puns and parodies and classics. In this, kudzu flour and abekawamochi from Kakegawa, warabimochi from Nissaka, amenomochi from Sayo no Nakayama, kashiwamochi from Sarugababa, and todango from Utsunoya appear as famous confections.

Next Part 3:

Wagashi in Japanese literature