Kachigumi and Makegumi

Those believing in a victory of Japan

With the discontinuation of Japanese language newspapers in June 1941, even if the Japanese were able to read Portuguese, they considered that articles in the Brazilian Portuguese language newspapers were propaganda messages prepared by the Allies and unreliable, and that the information alone which was obtained directly from Japan via shortwave radio and then transmitted by word of mouth was regarded reliable. They did not think that Japanese broadcasts also contained propaganda messages, like the Allies’s ones.

On August 14, 1945, it was possible to hear a broadcast of Japan's acceptance of the Potsdam Declaration even in Brazil, and Japanese people were stunned to hear of the country's defeat. But when some time passed, instead of accepting the defeat of Japan which was very difficult for them to accept, some people distorted and reinterpreted the information they had received up until then, according to their own wishes, and began to insist that the news of the defeat of Japan was false propaganda and that Japan had actually won the war. Such insitence quickly spread among Japanese people, and was believed by a large number of people who did not want to believe that Japan had been defeated. Those people were referred to as "kachigumi" (victory group), "senshoha" (war victory group), or "shinnenha" (believers).

Many leaders of the Japanese community were able to accept the defeat, most of ordinary people, however, especially those living in outlying areas, believed that Japan had won. This phenomenon did not occured only in Brazil, but some of Japanese people resident in Hawaii, Peru and other countries, and Japanese POWs interned overseas who could not see burnt out cities by air raids and needy people’s lives with an extreme lack of supplies with their own eyes, also believed in a victory of Japan.

Rash of fraud

In September, a rumor circulated that a Japanese delegation would come on board a warship from Japan to console Japanese people in Brazil, and Japanese immigrants rushed from outlying regions to the port of Santos. Even before the Pacific War, there had already been black market trading of Japanese yen (Bank of Japan notes, for it was believed yen would be necessary to eventually return to Japan, many fraud cases of tricking Japanese immigrants into buying yen bills which had become rubbish with the conversion of the currency to the new yen happened during this period. There were various other scams involving a fictional victory of Japan during this period and there were many victims of these scams among those who believed Japan had won the war.

Recognition movement

Leaders of the Japanese community feared that imprudent actions taken by many Japanese people who insisted on denying the defeat of Japan would cause all the Japanese immigrants to be excluded from Brazilian society, and the leaders started a "movement for the recognition of the situation" (or simply "the recognition movement") to satisfy those who believed Japan had won the war of the reality of the defeat of Japan and the current conditions the country found itself in, and to convince all the Japanese people in Brazil to think together about how they should behave in Brazilian society. Those that joined this movement were referred to as "ninshikiha" (recognize group), "makegumi" (the group accepting the defeat), or the "haikiha" (those wishing for defeat, used pejoratively by those in the "kachigumi" (victory group)).

On October 3, 1945, after receiving through the Brazilian branch of the International Red Cross, a copy of the imperial rescript ending the war and a message from Minister for Foreign Affairs Togo addressed to Japanese residing abroad, a ninshikiha (recoginition group) member Chibata Miyakoshi (former charge d'Affaires ad interim to Argentina and former director of the Brazil branch of Kaigai Kogyo Kabushiki Gaisha (Overseas Enterprise Company Limited)) convened several influential members of the Japanese community in Brazil. They decided that the contents of these messages should be conveyed to the Japanese immigrants. This action, however, simply served to further infuriate the senshoha (war victory group), who attacked Miyakoshi and the others as "traitors" and "disloyal to the country". For this reason, Miyakoshi had originally planned to visit the major settlements in outlying regions and directly explain the contents of the messages, but juding that there was a danger to himself, he abandoned this plan and instead decided to send printed copies of the imperial rescript and the Minister for Foreign Affairs’ message to outlying regions.

On October 19, members of the ninshikiha (recognition group) asked the U.S. Consul General in São Paulo to obtain recent newspapers and magazines from Japan in order to show the truth about Japan, and the requested materials, arriving on March 16, 1946, were immediately sent to communities in various regions.

Terrorist attacks by extremist elements of the senshoha (war victory group)

The situation, however, worsened and from March 1946 onwards there were frequent terrorist attacks carried out against the ninshikiha (recognition group) and leaders of the Japanese community by members of an extremist faction of the kachigumi (which were referred to as the "tokkotai" meaning not "special attack unit" but "special action unit"). On March 7, Ikuta Mizobe, executive director of the Bastos Industrial Cooperative was killed, on April 1, Nomura Chuzaburo, director of the Association for the Promotion of Japanese Education was killed (Former Japanese Ambassador to Argentina Shigetsuna Furuya was also attacked on the same day but the attempt failed), and on June 2, Jinsaku Wakiyama, retired Japanese Army colonel and chairmen of the Bastos Industrial Cooperative was killed. In addition, people participating in the recognition movement were also attacked in outlying regions and there were also cases of bombs being sent in small packages.

In an attempt to calm the situation, the Consulate of Sweden Japanese Rights and Interests Section distributed a message from Prime Minister Yoshida on June 3, and on July 19, the São Paulo State administrator gathered approximately 600 representatives of the senshoha (war victory group) from various regions and attempted to persuade them, however the senshoha (war victory group) members would not listen his persuasion at all.

Between July 30 and August 2, there were riots and bloodshed between Japanese and Brazilian residents in the city of Oswaldo Cruz on the Paulista railroad.

The Brazilian Government arrested a number of people consisting not only of those directly involved in the attacks, but many who were affiliated with the Shindo Renmei, a senshoha (war victory group) society, sending some of those arrested to the prison on Anchieta Island, off the northeast coast of the State of São Paulo and a measure was approved which provided for the deportation of them (forced extradition to Japan) in three groups from August onwards (the measure, however, was never actually carried out).

Ban on the entry of Japanese immigrants

The terrorist attacks committed by Japanese people were widely covered in Portuguese language newspapers, which caused anti-Japanese sentiment to grow significantly among Brazilian people. Around this time, on August 27, a proposal to add the clause to the new constitution which should bar the entry of Japanese immigrants in the country was being discussed in the Constitutional Convention. The proposal was rejected after the chairman cast a deciding vote against the proposal to resolve a deadlock, the reason for the rejection, however, was not that he was against prohibition of Japanese immigrants from entering the country, but that he deemed such a provision improper to be added in the constitution.

Postcards sent by relatives and friends in Japan

Amid the chaos caused by the terrorist attacks, the ninshikiha (recognition group) provided the U.S. Consulate General in Brazil with a list of 52 persons including arrested members of the Shindo Renmei, which contained their addresses and names and contact information of their relatives and friends in Japan so that these 52 persons could receive personal letters from these relatives and friends revealing the actual conditions in Japan. The U.S. Consulate agreed to the plan and on May 21, the list was shipped from the U.S. Consulate in São Paulo to the U.S. Department of State, then the postcards were shipped based on the list from Japan in September, which arrived in Brazil in December.

The Swedish Government, the U.S. Department of State, the GHQ/SCAP and Japanese Government cooperated in order to control the situation, sending newspapers and Japanese films that showed the conditions in the country to Brazil. The GHQ/SCAP accelerated the reopening of the postal system to facilitate the exchange of postcards between Japan and the rest of the world and the service was reinstated on September 10. Following the advice of the Swedish representatives, the Japanese Government suggested on broadcasts on September 15 and October 4 that radio listeners should write to their relatives and friends, if any, in Brazil. 572 postcards were shipped to Brazil in September alone.

Ninshikiha (recognition group) "weekly reports" and "information"

Since the publication of Japanese language newspapers remained banned in São Paulo even after the war, the ninshikiha (recognition group) published and distributed the "Shuho" (weekly reports) (published by the Cotia Agricultural Cooperative, mainly consisting of essays) and the "Joho" (information) (published by Chibata Miyakoshi and others, mainly consisting of news articles). Both the newsletters discontinued in 1946, because the new constitution abolished the ban on the publication of Japanese language newspapers and the "Paurisuta Shimbun" (Paulista Newspaper), which took the point of view of the ninshikiha (recognition group), was first issued in January of 1947.

Thanks to the efforts of all of the persons concerned, Japanese community’s disorder calmed down after the final assassination on January 10, 1947. Wounds suffered by the Japanese community, however, were deep, and the opposition was not resolved completely until the mid-1950s.

Movement to provide relief for war damage to their countrymen

In addition to this, in March 1947, the Ninshikiha (recognition group), with the approval of the Red Cross in Brazil, formed the Japan War Victim Relief Association, which collected donations that were sent to the Relief for Japanese Refugees fund based in San Francisco or the Yuaihoshidan relief organization. The association used those funds to purchase relief supplies that were then distributed in Japan by the United Nations Licensed Agencies for Relief of Asia (LARA). These activities won support even among the senshoha (war victory group) and helped to ease the tensions that existed between the two factions.

-

False propaganda news (1)

False propaganda news (1) -

False propaganda news (2)

False propaganda news (2) -

Diaries of Masao Hashiura

Diaries of Masao Hashiura -

Articles in newspapers / magazines

-

Imperial rescript ending the war and a message from Minister for Foreign Affairs Togo conveyed by the ninshikiha (recognition group)

Imperial rescript ending the war and a message from Minister for Foreign Affairs Togo conveyed by the ninshikiha (recognition group) -

Original materials

-

View of the Anchieta Island Prison

View of the Anchieta Island Prison -

Boarding and departure when prisoners were released

Boarding and departure when prisoners were released -

Note Verbale on the expulsion of certain Japanese citizens in Brazil

Note Verbale on the expulsion of certain Japanese citizens in Brazil -

Stenographic record of the Constituent Assembly

Stenographic record of the Constituent Assembly -

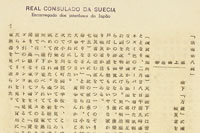

Swedish Consulate notice

Swedish Consulate notice -

Swedish Consulate notice published in a Portuguese language newspaper

Swedish Consulate notice published in a Portuguese language newspaper

-

U.S. Department of State document to the GHQ/SCAP Diplomatic Section requesting relatives and friends residing in Japan of influential Japanese immigrants to send letters to them

U.S. Department of State document to the GHQ/SCAP Diplomatic Section requesting relatives and friends residing in Japan of influential Japanese immigrants to send letters to them -

GHQ/SCAP measures

GHQ/SCAP measures -

Articles in newspapers / magazines

End of the ban on mailing envelopes between Japan and other countries

-

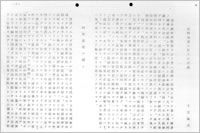

The "Joho" (Information) magazine

The "Joho" (Information) magazine -

Opinion of ninshikiha (recognition group) (1)

Opinion of ninshikiha (recognition group) (1) -

Articles in newspapers / magazines